Tunisia’s elections are to be held this Sunday, and the overdetermined winner will be the man currently serving as President: Kais Saied. The last holdout from the Arab uprisings, the country that gave democracy a chance the longest, Tunisia has descended headlong into autocracy under his rule. Nadia Marzouki, a brilliant Tunisian political sociologist, looks at one surprising factor in Saied’s centralization of absolute power—his unholy alliance with the Tunisian left.

Our other commissioned piece this issue centers on political economy, specifically the venerable question of growth and its limits. Economist Steve Keen picks apart Daniel Susskind’s new book which updates the neoclassical thesis yet in doing so falls into many of its customary traps. Keen goes back in time to an economist of yore to address the contradictions.

This issue’s curated content leads with an essay from Samuel Charap and Miranda Priebe, which nimbly deconstructs a commonplace set of assumptions about Russian power and should be required reading for those who jump to facile conclusions about Russian behavior. We follow with Patrick Iber’s reappraisal of The Age of Extremes, the final volume of Eric Hobsbawm’s classic tetralogy. Published thirty years ago, Hobsbawm’s book was a tonic to the giddy 1990s, a time when liberals chest-thumped with confidence that the future belonged to them. Economic historian extraordinaire Adam Tooze also has something to say about how a 1990s unipolar Western-centric mentality blinded us to key dimensions of the climate debate.

We end with a screed: Nathan Robinson’s no-holds-barred demolition of The Atlantic magazine. Robinson may not be burdened by subtlety, but his skewering of the quintessential middlebrow publication is a sight to behold.

Our musical selection this week is from the recently passed alto saxophonist and Philadelphian Benny Golson, who made a splendid career playing high-end hard bop. Your editor happened to pen an obituary of him in the Gray Lady last week. Here is Golson playing with trumpeter Art Farmer and their esteemed Jazztet the Thelonious Monk standard “Ruby, My Dear.”

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Tunisia

When obsolete anti-imperialism kills democracy

Nadia Marzouki

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Many activists on the left have been willfully blind to Kais Saied’s authoritarianism in Tunisia since his self-coup in 2021. While Saied constructed a classic populist narrative, building on collective frustration at the meager economic and political dividends of the 2011-2019 democratic governments, he has also benefitted from a segment of urban middle class intellectuals and organizers “who perceived themselves as under-appreciated, side-lined and betrayed by the post-2011 coalitions,” argues Marzouki. Some have turned a blind eye to Saied’s anti-democratic actions, choosing to see him instead as a herald of anti-imperialism.

“In its nativist and nationalist iteration, the anti-imperialist narrative that has enabled Saiedist supporters is not just anti-democratic. It is obsolete. It situates the locus of anti-imperialist struggles solely at the level of the nation state at a time when a significant part of today’s decolonial political debates, despite all their internal diversity, revolve around centering peoples and communities rather than states, and when ideas such as diasporism, exile, transnational solidarities are key to the thinking of non or post Zionism and post supremacism. The silence of “decolonial” Saiedists vis à vis the plight of Sub-Saharan migrants reveals how decolonialism works as a fig leaf for authoritarian and statist nationalism.”

Reckoning with Growth

Steve Keen

The Ideas Letter

Essay

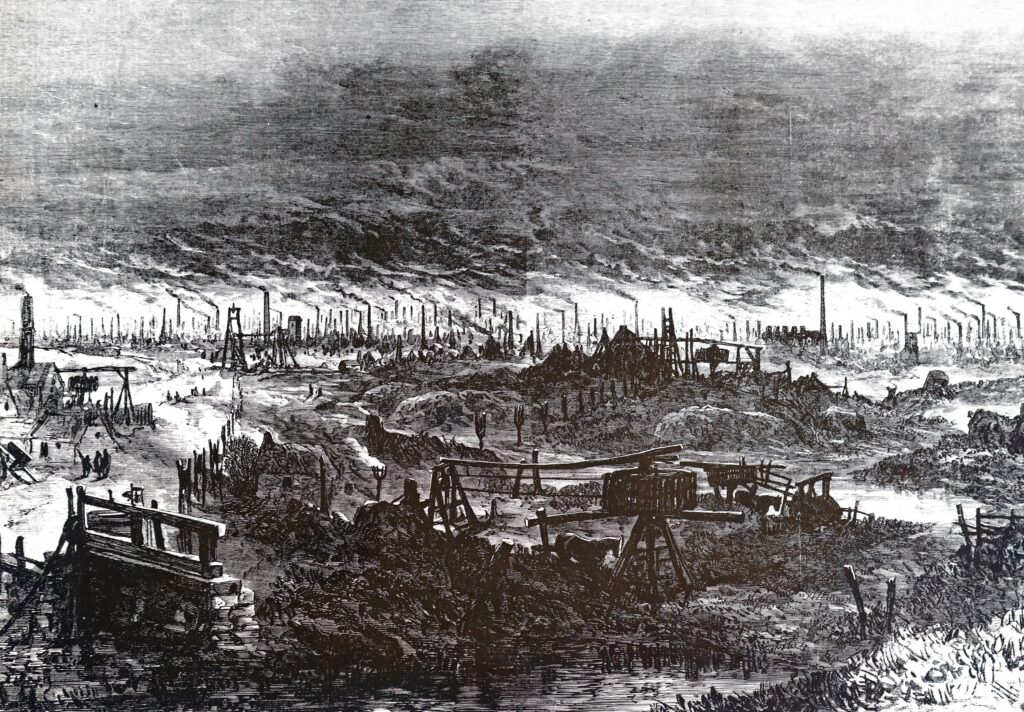

David Susskind argues that a dramatic increase in real wages in the United Kingdom starting in the mid-1700s, in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, is related to cultural changes that foregrounded “ideas” focused on improving people’s material lives. As Steve Keen writes in this review of Growth: A History and a Reckoning, this explanation is highly inadequate. Instead we should look to the work of William Stanley Jevons, one of the 19th century founders of Neoclassical economics, who argued that the answer to this spectacular growth was coal and its exploitation. The same is true today with energy in general, according to Keen.

“Of course, ideas are necessary to create the machines that harness that energy, but without that energy, those machines—from Watt’s original steam engine in 1776 to Musk’s Falcon Nine rockets today—would just be inanimate sculptures. … Economic growth therefore requires a growing use of energy. This is what makes continuing growth on our finite planet impossible, which Susskind quite literally denies when he states that ‘it is possible to have infinite growth on a finite planet’ (Susskind’s emphasis). His logic is an extreme version of the argument that a move towards a service-based economy will ‘decouple’ GDP from physical inputs … If only this were true, then human civilization would not be in peril from global warming.”

Further Reading

Growth: A History and a Reckoning

Daniel Susskind, New Books Network

Susskind counters the degrowth movement’s assumption that simply reducing growth will lead to better outcomes, and instead argues that “we should continue to pursue growth through the creative application of new ideas that allow us to use our finite natural resources more effectively and efficiently.”

Will Putin Stop at Ukraine? That’s the Wrong Question

Samuel Charap and Miranda Priebe

The Washington Quarterly

Article

Charap and Priebe analyze four faulty assumptions driving current NATO strategies toward Russia: that Russia is rapidly rebuilding its military capabilities, NATO’s deterrence is insufficient, Russia is likely to engage in opportunistic aggression, and a Russian victory in Ukraine would threaten NATO’s security. They argue that these assumptions lead to a narrow focus on preventing Russian aggression postwar while ignoring more plausible conflict scenarios, such as war from escalation or first-strike pressures. NATO should adopt a broader strategy aimed at preventing these more likely threats, addressing sub-conflict challenges, and stabilizing European security.

The periods following major wars are precisely the moments when states should seek to keep their options open; the policy choices that the United States and other powerful countries make—or do not make—in a war’s aftermath tend to have long-term effects. … The Russia-Ukraine war is not a global systemic conflict as of this writing; its end therefore might not present a global ordering moment. However, the choices around even regional wars have resulted in arrangements that define regional security and create durable patterns of relations. … US and allied policymakers’ decisions after the hot phase of the Russia-Ukraine war comes to an end will likely have significant long-term effects on Western interests. But today’s rhetoric about the Russia threat could constrain options at what will be a critical time.”

Eric Hobsbawm’s Lament for the Twentieth Century

Patrick Iber

The New Republic

Essay

British historian Eric Hobsbawm’s The Age of Extremes was a global bestseller when it was published in 1994, the last in a tetralogy explaining the “long nineteenth century” and the “short twentieth.” For Hobsbawm the former was defined by material, intellectual and moral progress, the latter by regression. Patrick Iber reflects on the lasting impact of a brilliant historian’s greatest work.

“Thirty years later, does The Age of Extremes hold up? Many of its good qualities remain. Hobsbawm remains a brilliant writer and communicator. It is impressively wide-ranging, covering the arts and sciences along with politics and economics. Its Marxism both helps and hinders the text. At times, he strains to explain things that don’t need explaining, and he seems uneasy with social changes that another historian might see as demonstrations of moral progress. But if a classic is a work that remains worth reading both for what it is and for what it tells us about the time it was created, Hobsbawm’s text deserves that status. It rewards the reader not because a historian would write the same book today but precisely because they would not.”

Putting the unipolar epoch of climate politics in its place. Or, the mixed economies of the climate crisis

Adam Tooze

Chartbook

Article

Climate politics in the West must grapple with the fact that China dominates the global emission’s balance, and there is little reason to believe Beijing’s policy is meaningfully impacted by “the erratic and inconsistent decision-making of the West.” The West faces the unsettling prospect of authoritarian China taking the lead on climate policy. This state-led decarbonization seems anomalous, but actually, at the birth of modern global climate politics in the 1980s, “the political economy of the crisis was understood as “mixed” and polycentric,” explains Tooze.

“It was only in the course of the 1990s that the fossil-fuel-driven climate crisis was reframed in unipolar terms, as primarily a US-driven phenomenon … The efflorescence of Marxisant writing on the climate crisis and long durée histories of the “capitalocene” have contributed to the intellectual charisma of this Western-centric reading. For political purposes, the imagery continues to serve useful political purposes today. But, both as history, when we approach the mixed economy of energy in the postwar “great acceleration”, and as an analysis of the climate crisis in the 21st century it is fundamentally misleading. It should be understood as an epochal political and intellectual accompaniment to the unipolar moment of the 1990s, an era which is now behind us. To the extent that that vision of the climate crisis continues to resonate, whether in affirmative and critical takes on Western “climate leadership”, it is a marker of our disorientation.”

The Worst Magazine In America

Nathan J. Robinson

Current Affairs

Essay

Robinson criticizes The Atlantic for publishing bad ideas by presenting poorly reasoned arguments and superficial analyses that mislead readers. It fails to rigorously support claims made in its pieces, often omitting crucial counterpoints, he writes. Examples include pieces on Medicare for All and the defense of Henry Kissinger. This casual treatment of serious issues contributes to a decline in public debate, as factually incorrect and unsubstantiated ideas make their way into the mainstream, argues Robinson.

“… I want to explain exactly what it is that I think makes The Atlantic terrible and why I think we’d all be better off if it stopped publishing. My basic criticism is that while it presents itself as a magazine of ideas—which makes readers feel as if they are engaging intelligently with important issues—it in fact covers those issues in such a superficial and slipshod way that people are liable to be left with a worse understanding of the issue than when they went in, though they may be wrongly convinced that they have learned something. I do think that the ideological suppositions that predominate (with exceptions) in The Atlantic’s pages are dangerous and wrongheaded, but my critique of the magazine’s glib carelessness with ideas would be valid even if I was not also annoyed by its tendency to publish aggressive criticism of my fellow leftists and a never-ending sequence of cheap swipes at protesters.”