Bhaskar Sunkara, the founder and editor of Jacobin magazine, has earned a reputation as one of the sharpest and most informed voices of the social-democratic left. For The Ideas Letter, Sunkara explores the manner in which social-democratic parties have lost their way and considers how their relations with the working class might eventually be re-woven. It’s a story and a struggle of manifold importance.

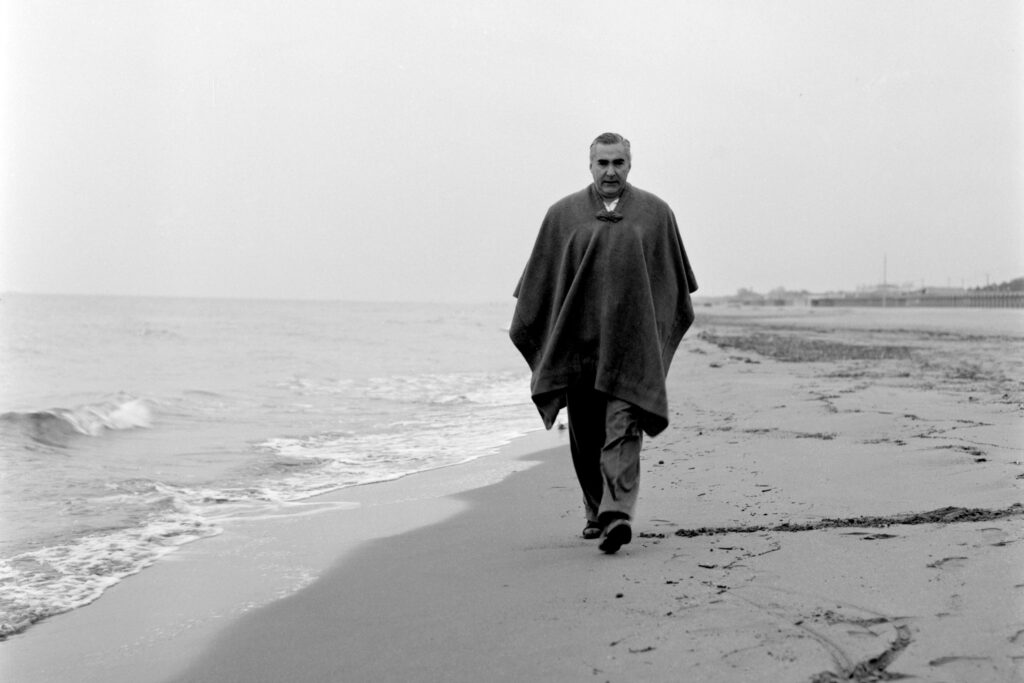

In a piece that could not be more different from Sunkara’s, the legendary essayist and aesthete Gary Indiana vividly details the life and times of the notorious Italian writer, Curzio Malaparte. As one colleague suggests, Malaparte’s writing (and Indiana’s retelling) might be seen as the literary equivalent of Bernardo Bertolucci’s Il Conformista—a manifestation of fascism in everyday life. No one narrates a life quite like Indiana and we are damn lucky to have him in our (digital) pages.

For our curated section, we lead with a vital essay from Matthew Flinders, who casts a skeptical (if not jaded) eye toward the academe’s contemporary lust for impact and relevance. Amy Kapczynski follows with a plea to extend industrial policy into more and more spheres and sectors; only then, she argues, can its nexus with democracy be appropriately effected.

Claudio Pinheiro challenges us to think about the terms of art “Third World” and “Global South”—concepts shot through with ideological assumptions and preconceptions. Laying those assumptions bare is a necessary first step to reconceiving their application.

Finally, the versatile Shanghai-based writer Jacob Dreyer, in an essay from Noema, asks some challenging questions about China and Eurasia and arrives at more than a few uneasy conclusions.

Our musical selection for Ideas Letter 26 comes from the uber-hip Chinese jazz diva Mandy Chan: “Give Me A Kiss” (给我一个吻, Gei Wo Yi Ge Wen). Enjoy!

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Social Democracy After Class?

Bhaskar Sunkara

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Sunkara argues that social-democratic parties, traditionally the political expression of working-class interests, have de-aligned with their core social base due to economic changes and political shifts over the past few decades. Faced with economic crises, these parties took the side of capitalist interests, a decision that left workers politically unmoored and available for electoral poaching by the right. The left has increasingly represented professional classes, ignoring the role of political victories in Fordist stability and “that the rise of the precariat is itself related to defeats suffered by social democrats and trade unions.” Social democracy’s future depends on reconnecting with workers and their material needs, rather than relying on ideological coalitions detached from the economic struggles of the working class.

“Ultimately, the left can’t win enough power to change society without foregrounding bread-and-butter concerns and rooting itself in the constituencies that would benefit the most from the redistribution of resources. That means a commitment to solidarity in many forms, but it also means ultimately recognizing that victory is not possible without the support of people who might have all sorts of contradictory, even reactionary, views. Without this basic realization, the new social democrats will sound like the old communist bureaucrats in Bertolt Brecht’s 1953 poem “Die Lösung” who, after an uprising, propose dissolving the people and electing another.”

Malaparte!

Gary Indiana

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Indiana explores Italian writer Curzio Malaparte’s oeuvre—his self-aggrandizing, his contradictory literary persona, and his depictions of war and power. Malaparte’s vivid descriptions of atrocities provide insight into the brutalities of modern warfare. That much of his purported reporting is fictional only makes it more literarily fascinating. But his self-serving tendency to place himself at the center of events—and his comfort within fascist Europe—undermines Malaparte’s moral authority and complicates his legacy.

“Malaparte was a more splintered, equivocating personality. He lacked any firm convictions, but repined for certainty of some worldly or unworldly sort, a durable belief system to curtain off the void. He willed himself into one ideological stance after another, in a struggle against the intolerable recognition that he couldn’t believe in anything except the certainty of death. The tension of this conflict intermittently rescues him from rhetorical banality. His intent is more confused, and confusing, than Gombrowicz’s ever could have been. Malaparte’s infernal ‘I’ that spills all over the place in his writing aims past a strictly literary audience, at a political constituency: before and during part of World War II, he stayed within fascist propriety while gingerly testing it, not because he opposed it per se, but because he felt uniquely exempt from the oppression of everyone else. Later, he distanced himself from any association with fascism, presenting his complicity as a highly rarefied form of opposition.”

Impotence Through Relevance? Faustian Bargains, Beyond Impact and the Future of Political Science

Matthew Flinders

Swiss Political Science Review

Academic paper

Flinders highlights the shifting relationship between the academe and society, with scholars expected to collaborate on state-selected societal challenges and demonstrate impact. This pushes researchers to trade their traditional criticality and independence in order to access funding. Flinders’ “impotence through relevance” thesis suggests that academics hailed as highly impactful may actually be irrelevant, while those with transformative potential are sidelined as unproductive. This dual phenomenon raises concerns about control of scientific research and democracy.

“Put very simply, the very essence of political science revolves around the analysis, understanding and questioning of power. … criticality vis-à-vis power exists as the very ‘soul’ of political science and, as such, a political science which allows itself to be co-opted or is not, at least, alert to the risk has in essence ‘sold out’. When faced with growing inequality, climate change and an array of societal challenges it is not the role of the social and political sciences to produce empirical intelligence about ‘what works’, or to tinker at the edges of existing policy or institutional design. It is the job of those disciplines to retain and sustain a sense of radical ambition which is why political science ‘needs to talk’—to paraphrase Smith and Stewart (2017)—far more loudly about the changing research landscape in order to politicise a number of processes.”

Further Reading

Science as Public Service

Hannah Hilligardt, European Journal for Philosophy of Science

“… normative judgements in research need not be democratically legitimated in order for science to be democratically legitimate. Indeed, it can be democratically legitimate for scientists to go against the expressed views of the public or political representatives if this is justified in light of, firstly, the role science has been asked to fulfil and, secondly, when it is in line with public institutions’ key principles. This is a counter-position to views currently held in the values in science debate … which argue that value-laden judgements in science are legitimate if they are aligned with the public’s views or directly decided by public.”

Industrial Policy as Democratic Practice

Amy Kapczynski

Democracy

Essay

Industrial policy designed as a democratic practice can revitalize both the economy and democracy itself by promoting public aims and addressing structural inequalities. Kapczynski emphasizes the need to strengthen administrative power and cultivate countervailing power among marginalized communities to ensure accountability and fairness. She advocates a broad, developmental approach to industrial policy that extends beyond manufacturing and uses government tools to shape sectors like clean energy and care work, with the ultimate aim of creating an economy that benefits everyone.

“Part of the reason industrial policy is rightly back is that new evidence and scholarship have revealed the flaws of the neoliberal paradigm and shown us that government must play a significant role in an economy like ours, and that it can do so effectively. Today, it is ever clearer that good jobs, a more fair and dynamic economy, and more resilient energy and care infrastructures require a vibrant role for the state. This is not just because the neoliberal ‘free market’ is tilted toward the privileged or lacks both the fluidity and resilience we need (see the recent supply chain disruptions and energy shocks). It is also because the state alone is well situated to finance long-term and high-risk innovation, to overcome coordination problems, and to invest in the development of interdependent goods, like the workforce and roads and subsidies needed to build semiconductor and clean energy sectors.”

Further Reading

Industrial Policy Without Nationalism

J.W. Mason, Dissent

“As a matter of economics, then, there is no reason that industrial policy has to involve us-against-them nationalism or heightened conflict between the United States and China. As a matter of politics, unfortunately, the link may be tighter.”

From the Third World to the Global South

Definitions of Moral Geographies of Inequality in Anti-Colonial Intellectual Traditions

Claudio Pinheiro

Sociology Compass

Academic paper

The term “Third World” was traditionally used to describe regions seen as lacking in prosperity and development, while also serving as a symbol for anticolonial resistance. The concept highlighted the unequal distribution of power and wealth after World War II, replacing colonial forms of oppression and spurring movements for liberation and autonomy. In contemporary debates on intellectual decolonization, the term “Global South” has gained popularity as a way to express similar ideas, which Pinheiro dubs “moral geographies of inequality.”

“The Third World and the South are polysemic terms with different genealogies. While the terms were largely assumed as synonyms, their trajectory and usages speak for different histories. One challenging dimension is how the South relates to the question of ontology, that is, to the social sciences’ ability to address a diversity that is represented as a moral geography of inequality. Is it possible to replicate the economic and epistemic divide between spaces of wealth and progress and zones of accumulated loss, poverty, and absence, to speak of geographies of ontological inequality? Would this divide then refer to the difference between whiter and ‘darker nations’ … meaning that the South would stand for a racial and racially aware topography in terms of universalized ontologies produced by colonialism, capitalism, and Modernity? Otherwise, should we assume that there is a scale able to provide the methodological lens and the platform that would be required to reorganize our understanding of what makes historically constituted minorities unique?”

Further Reading

Gaza, South Africa and the Return of the Third World: Towards a Postcolonial Humanism

Julie Billaud and Antonio De Lauri, Humanity Journal

“International law has historically been manipulated to render acceptable the suspension of liberal normative standards when it comes to violence and suffering perpetrated against non-Western populations. Yet the litigation initiated by South Africa against Israel at the International Court of Justice illustrates the Global South’s unwavering commitment to challenge the international world order through legal means. Can the case of Palestine propel the ‘return’ of the political project of the Third World on the international stage and revive its insurgent and decolonial spirit at the very moment when genocidal erasure looms in Gaza?”

China Builds A New Eurasia

Jacob Dreyer

Noema

Essay

China’s ambitious efforts to decarbonize are restructuring the global economy and shifting the geopolitical balance in Eurasia. As China dominates renewable energy development, especially in solar and wind power, it is creating new economic and political ties across Asia, while challenging the U.S.-led petrodollar system. This transformation is also influencing regions like Mongolia and Saudi Arabia, which are adapting their economies to benefit from or resist China’s growing influence, reshaping global alliances and resource dependencies in the process.

“At the heart of the contemporary Chinese empire is a digital megastructure that might be the true protagonist of our time, reordering energy, land, and human life around its need to adjust to a new enviro-political reality. When COP29 opens in November in Baku, a Eurasian city built on oil that is today crisscrossed by infrastructure with Chinese characteristics, a latter-day Pax Mongolica will see itself in the mirror: a Sinified Eurasian continent remaking itself with renewable power. … For those who think in English, this can all feel like the realization of a baleful prophecy about the emergence of a totalitarian empire. But if the Eurasian steppe is the backdrop to human history, it’s a history of human insignificance in the face of natural forces and distances. Preoccupation with emperors misses the deeper truth of people lost in an endless emptiness, searching for meaning and for a way to transform their circumstances.”