Undefining Woke

A response to Gary Younge

I share a lot in common with Gary Younge. We’re both black sociologists with deep ties to journalism, and to The Guardian in particular. For all that, we do have very different formal training and life experiences, and we see the world in importantly different ways. These latter facts were on clear display in Professor Younge’s recent review of my book, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite (2024, Princeton University Press).

I’m gratified he read the book, and I’m thankful for his remarks which, while often critical, were also helpful for marking out some important divides within the symbolic professions. The Ideas Letter’s invitation to respond to Younge’s review provides an opportunity to sharpen those divides further while clarifying the intended contribution of the book. Here I’ll focus on three places where Professor Younge and I diverge in ways that I think are generative and revelatory.

Definitions are not spells

The title, We Have Never Been Woke, is a nod to a different text by another sociologist: Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern. Younge claims of my book that, “A significant part of the problem can be found in the title. Latour at least defines modernity before claiming it never existed.”

This is a strange claim… namely because it’s not true at all.

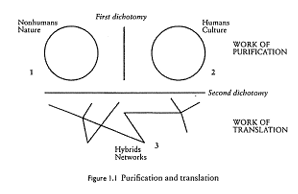

The closest Latour comes to a concise definition of modernity appears roughly a tenth of the way into the body of the text when he tells us that “the word ‘modern’ designates two sets of entirely different practices which must remain distinct if they are to be effective, but have recently become confused.” Over the paragraph that follows, he identifies these two practices as translation and purification. The end of that paragraph is followed up by this diagram:

Is everyone clear on what “modernity” is now? Likely not.

Latour later sketches out a “constitution” of modernity – comprised of four core guarantees (that derive from two central paradoxes). However, there is nothing even remotely approaching a straightforward, dictionary-style, tweet-length definition of “modern” or “modernity” anywhere in the book.

It’s worth belaboring this point because, after mischaracterizing Latour’s book, Professor Younge spends about half of the critical portion of his review chastising me for not defining “woke.” It’s true: I don’t define the term. But what Younge declines to acknowledge are the reasons I give for not defining the term, and the deep context I provide in lieu of a definition. So I’ll run through it briefly here.

In my view, people overfocus on definitions in a way that actually distracts from understanding substance. In some circles, people claim that if you can’t or won’t define a term, then you must not know what it means. Absent definitions, they suggest, one is unable to use words ‘correctly’ (such that your meaning is consistently well-understood by your audience). But as I explain in the text (pp. 29-31), this is balderdash. It’s not the way language works at all.

And “woke” isn’t just any word, it’s a highly contested term. As I write in the book, if I had simply paved over the disputes around the word in order to advance a clean definition that suits my own moral, political, or scholarly project — this would be far less clarifying than what I decided to do instead, which was to surface how different stakeholders understand and mobilize the term.

I spend several pages, right at the outset of the first chapter, going into the history and contemporary usage of “woke” including explorations of the different ways people have tried to define the term, and the different postures various stakeholders adopt with respect to it. And it’s not just “woke” that gets this intensive treatment. The book identifies and analyzes the evolution of other words that have served a similar discursive function in the past (such as “political correctness”) to help contextualize the current and likely future trajectory of “woke.”

Thereafter, I provide a list of beliefs and dispositions that people across the political spectrum seem to associate with “wokeness” (pp. 31-32). I explore the prevalence of these dispositions in American society, showing that they are most common among institutions and constituents associated with the symbolic professions (and they’re really uncommon among people who are not relatively-affluent, highly-educated, urban and suburban whites). I conclude the first chapter by providing a historical account of why these beliefs came to be associated so robustly with the symbolic professions and got bound up with our claims for wealth, status and autonomy (pp. 57-66).

All of this provides a much richer understanding of how people understand the term than a simple dictionary definition would. But, strikingly, none of this rich detail about what “wokeness” means was mentioned in Professor Younge’s review. Based on his characterization, you’d think I just thumbed my nose at clarity, and then moved on to other topics, deploying the term throughout the text in a capricious way – inviting, or in any event, allowing others to follow suit.

Younge argues that, “since [al-Gharbi] does not own the word he cannot control how it is understood and employed beyond the covers of his book.” This is unquestionably true. But of course, even if I had defined the word, I would not be able to “control how it was understood or employed beyond the covers of my book.”

Kimberle Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, et al. “owned” critical race theory. This did nothing to stop Christopher Rufo from unapologetically branding everything he didn’t like “CRT.” Nor did it stop Republicans from effectively capitalizing on the moral panic Rufo successfully engendered around the term. Likewise, Marxists “own” communism. This doesn’t stop right-wingers from branding everything they don’t like as some form of “communist” (including branding wokeness as “postmodern neo-Marxism” or “cultural Marxism”). Definitions are not magic spells that bind the political opposition. As I explore at length, even if you introduce a new term into the “language game,” you can’t control how it is interpreted and used once people start engaging with it en masse. If you’re talking about a century-old term that’s already highly-contested, forget about it. There’s simply no way that providing a definition in my book would have somehow ended the culture wars around “wokeness.”

What about the actual capitalists?

The “we” in We Have Never Been Woke is a constellation of elites that I call symbolic capitalists – professionals who work in fields like finance, consulting, law, HR, education, media, science and technology.

On Professor Younge’s account, my focus on these elites is misplaced. It’s the billionaires and politicians who truly call the shots in society. The rest of us are, apparently, just helpless pawns in their game. At one point in the review he rhetorically asks, “When the concentration of wealth and power is escalating at the rate that it is, wages have been effectively stagnant for the best part of half a century, economic and racial inequalities are growing… where is the evidence that academics, consultants, lawyers and journalists dominate much beyond their own realms?”

To put it mildly, the evidence is overwhelming. As Katharina Pistor powerfully illustrated, capital is literally a product of legal coding. The rich and powerful protect and reproduce their social position through regulatory capture and other legalistic means. If you want to understand the concentration of wealth and power, it’s hard to see how you get there while ignoring the role of the law and lawyers.

Indeed, the U.S. has one whole branch of the government, the judiciary, that is exclusively run by symbolic capitalists. With respect to the legislative branch, according to contemporary New York Times estimates, more than 70 percent of Congresspeople are former white collar professionals. What about the executive branch? Well, every Democratic president since Jimmy Carter has been a lawyer (alongside failed Democratic nominees Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, Mike Dukakis and Walter Mondale. Al Gore, meanwhile, was a former journalist). Even on the Republican side, symbolic capitalists have been hugely influential: Richard Nixon was a lawyer. Ronald Reagan was an actor. JD Vance was a bestselling author and finance bro (who also possesses a law degree). And as for his boss, Donald Trump’s real estate and construction businesses generated consistent losses: he secured his wealth primarily through appearances in television, movies and commercials and then licensing his “brand.” All said, symbolic capitalists absolutely dominate all branches of the government. Hence, if Younge wants to understand “the composition of the Supreme Court and the evisceration of reproductive rights, voting rights and gun control that has come with it” his analysis should clearly start with the symbolic professions.

I dedicate a full chapter of the book to driving this point home. Chapter 3 details at length how wealth and power have been consolidated into institutions, professions, and communities associated with the symbolic economy over the last century, at the expense of many stakeholders in society. I illustrate in great detail how the racialized inequalities Younge alludes to are actually far more pronounced in institutions and communities associated with the symbolic professions than elsewhere – and symbolic capitalists benefit from these inequalities more than most. Our social position is fundamentally premised on exploitation and exclusion. If Professor Younge was not persuaded by the extremely wide array of empirical literature I marshal on these points, it’s hard to see how he could possibly be persuaded by any amount of evidence given that, in his own words, I “examine almost every aspect of [symbolic capitalists’] lives from who they sleep with, vote for, donate to, what they read, earn, eat and spend and where they live and study, to make the case.”

Yet, to be fair, part of Younge’s claim is that I’m inconsistent in my arguments about symbolic capitalists’ clout. In his characterization, I describe symbolic capitalists as incredibly powerful and also highly marginal and ineffective. In fact, there is no contradiction here.

In most cases, symbolic capitalists directly reach a narrow and idiosyncratic slice of society with their work. However, it is in those sections that the folks we symbolic capitalists are most likely to reach tend to be wealthy, influential and well-connected. Symbolic capitalists and aligned institutions are immensely influential over other elites, even if we’re growing increasingly out of touch with almost everyone else. As it relates to our efficacy: the book emphasizes that symbolic capitalists are quite good at making things happen in general, but we tend to be really bad at social justice in particular.

One of the main reasons symbolic capitalists are ineffective in this specific domain is because we almost exclusively try to pursue social justice goals in ways that don’t entail any meaningful risks, costs or lifestyle changes for people like ourselves. This is because, while we’re sincerely committed to egalitarianism on the one hand, we’re also sincerely committed to being elites on the other: we think our perspectives and priorities should count for more than the folks checking us out at the grocery store; we think we should enjoy a higher standard of living than the folks delivering our packages; we want our children and partners to reproduce or exceed our own position. This set of drives is in fundamental tension with our commitments to social justice. After all, you can’t really be an egalitarian social climber. It’s a contradiction in terms.

The main way symbolic capitalists try to square that circle – to simultaneously enhance our position as elites and our bona fides as egalitarians — is to expropriate blame to, and attempt to extract resources from, those who are still more elite than ourselves.

Since Occupy Wall Street, our preferred foil has been the dreaded “1 Percent.” As Chapter 3 details, these super elites do hold a large and growing percentage of resources in the U.S. and beyond: the top 1 Percent closed out 2022 controlling 26 percent of all America’s wealth. This is a radically disproportionate share. Notice, however, that they do not control a majority of U.S. wealth. They don’t control anything near a majority. Consequently, if you only focus on the top 1 percent, you miss the vast majority of American assets.

What if we zoom out to the upper quintile – if we look at the billionaires, millionaires and the upper middle class? Then we can account for 71 percent of the country’s wealth. Another way of saying this is that the bottom 80 percent of Americans make do with roughly one-quarter of the country’s wealth. Notice also that percentiles 2 through 20 collectively control much more wealth than the top 1 percent – almost twice as much. But the operation of this wealth is conveniently rendered invisible when we focus tightly on the pinnacle of the wealth distribution.

As Richard Reeves put it, narratives like “we are the 99 percent” primarily serve to help multimillionaires and people with healthy six-figure incomes pretend to be “ordinary Joes.” It does nothing for Waffle House workers to pretend like someone with a million dollars in assets and a $200,000 salary is in the same financial “boat” as themselves. However, it’s super convenient for these affluent folks to portray themselves as “middle class,” and to define themselves in contradistinction to the billionaires, who purportedly deserve all the blame for social problems. Yet, as Reeves’s research illustrates, opportunity hoarding by folks in the upper quintile drives rising inequality and declining social mobility much more than the actions of the top 1 percent. Put simply, “we are the 99 percent” is a discourse that primarily serves the interests of the wealthy, not the poor.

A core project of the book is to zoom out to see a fuller picture of wealth and power: who owns it, how it is acquired and maintained, how it is leveraged, and towards what ends. Ironically, it is precisely for this that Professor Younge accuses me of having “erected a system of thought about how society works that bears little relation to the system of power.” Yet, in truth, it’s impossible to understand how power actually operates in society today without looking at symbolic capitalists.

A quick example. Anand Giridharadas’ Winners Take All explores how billionaires and the corporations they helm foment all manner of social problems through the myopic pursuit of profit maximization – and then they leverage philanthropy to paint themselves as the solution to those very problems. There’s a way of analyzing this phenomenon focused strictly on the billionaires and capitalist enterprises per se. But this would miss most of the story. If we think in more concrete terms about how and why things happen, it quickly becomes clear that the billionaires don’t actually do much of anything in the process Giridharadas describes.

Who are the PR professionals that help spin these donations into positive perceptions while minimizing negative publicity for the harm they cause? Who are the journalists who write the fawning profiles after these donations, helping them launder their reputations? Who are the folks who administer these nonprofits through which the super-rich attempt to influence society? Who moves the money and documents around to make all this possible? The answer in each of these cases is “us,” the symbolic capitalists. We’re the ones who actually do the things. The billionaires are not designing and implementing their own PR strategies, interviewing themselves for the news, and then writing, publishing and disseminating their own puff pieces. They aren’t drafting their own contracts, moving their own money around, or administering their own nonprofits. All of this stuff instead happens with and through symbolic capitalists and it literally could not happen without us. And we profit immensely from carrying out this mystification work, alongside our clients. Put simply, if you want to understand the system of power, you can’t focus narrowly on the super rich.

But, incidentally, even for those who want to ignore these realities and rail against the top 1 percent anyway, there’s also the inconvenient reality that America’s millionaires and billionaires are increasingly drawn from the symbolic professions too. In fact, this is an important detail for understanding the contemporary prevalence of “wokeness.”

Chapter 4 of We Have Never Been Woke details how these new symbolic economy oligarchs tend to fall far left of the median Democrat activist on “culture” issues (and the activists tend to be significantly to the left of rank-and-file Democrats who are, themselves, to the left of the median voter). Money from these culturally-left donors and foundations has played a major role in subsidizing left-aligned cultural outputs and dragging the Democratic Party and aligned activist organizations farther out of synch with the U.S. mainstream. If you want to look at how power actually works, it is very important to attend to these super elites – as my book does, and as most other work on these topics does not.

The influence of these left-aligned donors and foundations is likely far more important than right-aligned influence campaigns for explaining why huge swaths of society grew alienated from the Democratic Party. Even if we just look at the distribution of funding over the course of the 2024 campaign, disclosed donations and dark money from left-aligned industries, oligarchs, foundations and activist groups far exceeded the amount of money raised by Trump and the Republicans. Yet almost all the talk about the distortionary power of money in politics focuses on people like Elon Musk and Donald Trump – including, tellingly, in Professor Younge’s review – as though wealth and power were simply consolidated in the “other” sectors of society and not with “us.”

Just how rich and powerful are symbolic capitalist oligarchs? Well, if you look at Forbes’ estimates of the richest 10 people in the world, you’ll notice that they are overwhelmingly Americans, and the richest Americans are drawn almost exclusively from the symbolic professions. The companies through which these billionaires accrued their wealth include Facebook, Google, Berkshire Hathaway, Oracle and Microsoft.

And then there’s Amazon. When people think of the company, what first comes to mind is likely the online store. However, most fail to understand the store’s actual profit model. The lion’s share of income generated by Amazon.com doesn’t come from product sales, but from advertising. The marketplace website is primarily a conduit for delivering ads to consumers and collecting ad revenue from sellers. The actual merchandise is an afterthought – it’s often sold at a loss, well below MSRP (with devastating impacts on many local businesses and the communities they serve). Similar realities hold for Prime Video: Amazon typically spends more on acquiring content than they take in from subscription revenues and digital rentals or purchases. The main point of the digital content is to collect consumer data and deliver commercials on behalf of Amazon.com vendors. But, critically, none of these initiatives are Amazon’s main source of revenue. That honor goes to their Amazon Web Service data collection, analytics and storage enterprise – and it’s not even close. Amazon is primarily in the data business and, secondarily, the advertising business. All the other products and services they offer are just ways to collect more data and deliver more ads. Put another way, Jeff Bezos is fundamentally in the same business as Mark Zuckerburg. Both of their businesses generate income in the same ways. And they’re both symbolic capitalists.

The only U.S.-based “traditional” capitalist in the top 10 richest people in America is Elon Musk. His companies and wealth derive primarily from physical goods and services such as shipping and logistics (Space X), material extraction (The Boring Company) and auto manufacturing (Tesla). However, even Musk amassed his first hundreds of millions from two symbolic economy ventures: Zip2 (software) and PayPal (finance). And today, Musk is trying to make big plays into new symbolic industries like UX (Neuralink), telecommunications (Starlink), social media (X), and AI (Grok). So even the exception helps prove the rule: if you want to understand contemporary oligarchs, the symbolic professions are where the action is.

Indeed, even the “real” economy is largely controlled by the symbolic professions. For instance, decisions about whether a plant remains open or workers continue to receive their pensions are increasingly made by folks who work for McKinsey or Goldman Sachs in addition to (or more typically, instead of) turning on the whims of traditional capitalists. Folks seemed to have no problem understanding these realities when former Bain Capital executive Mitt Romney was running for president on the Republican ticket. But now that consulting and finance firms have become symbolic champions of causes like Black Lives Matter, feminism and LGBTQ rights (often coercing other companies into adopting the same posture) and donate primarily to Democratic politicians, the thread has somehow been lost. We’ve apparently reached a point where a left-aligned scholar and journalist could credulously ask whether consultants et al. actually influence society – and provoke many readers to nod along with this rhetorical question. This is a striking and distressing psychological transformation since the onset of the latest “Great Awokening,” but it only underscores the urgent need for my book.

Resisting #Resistance Lit

Readers seeking to know why mainstream symbolic capitalists (and aligned ideologies, institutions and communities) are “good” – and why our moral, political, cultural or socioeconomic rivals are “bad” – can choose just about any other piece of research or reporting on contemporary moral, political or cultural issues produced by mainstream academics or journalists. I didn’t see much value in contributing more to the heap. I wanted to try to do something different by analyzing “us” in the same way we typically analyze “those people” who are sociologically distant from us.

You might think that this approach would make the book easy culture war fodder for the right, especially given Professor Younge’s description of the text. In his account, the book “does not so much as lead us carefully through this [cultural] minefield as grab us by the hand as [al-Gharbi] performs the can-can across it with a herd of holy cows in tow, allowing the collateral carnage to fall where it may.” He elsewhere claims I dismiss “large sections of society and the opinions they hold both summarily and comprehensively.”

In reality, right-aligned critics have complained at length about the fact that I take symbolic capitalists as earnest and well-intentioned and explicitly rule out assumptions of cynicism. They have lamented that I largely argue within left-frameworks and even close the book by steelmanning many “woke” ideas. Others were frustrated that I ultimately make no judgements about whether the beliefs and aspirations of symbolic capitalists are “good” or “bad” or “true” or “false.” Many others have resented that I symmetrically analyze antiwoke and conservative symbolic capitalists alongside their progressive peers.

On the flip side, left-aligned critics have consistently praised the book’s charity, grace, generosity, sensitivity and nuance. We Have Never Been Woke was named one of the best non-fiction books of 2024 by Mother Jones who emphasized that “al-Gharbi’s tome isn’t a rant about ‘wokeness’; it’s a careful study of the highly educated, progressive-leaning world of what he calls ‘symbolic capitalists.’ That is, it’s a study of us: me, my colleagues, our bosses, our entire industry, the public figures and academic experts we often write about, and countless others with expensive degrees—all trying to leverage our new Bluesky accounts into a permanent place in these collapsing job markets.”

This latter point about the “collapsing job markets” is important. Pace Younge’s claim that I don’t talk about the workings of capitalism, a core contribution of the book is to move discussions of “wokeness” out of the realm of pure ideas and culture and into the material world. The book illustrates how periods of social justice fervor among symbolic capitalists seem to be driven by socioeconomic and cultural precarity among elites. And, turning the lens the other way, the book explores the practical consequences of our symbolic advocacy with respect to the vulnerable populations we purport to champion and represent.

But sitting with Professor Younge’s review, it seems like there is a deeper source of disagreement between us. The frustration that animated expressed disagreements about the alleged consequences of not defining “woke,” or the purported failure of the book to target the “actual” capitalists was due to an apparent perception that, at this moment, we need to direct all guns on the GOP and Trump. Work that directs attention away from “those people” is worse than useless – it’s actually dangerous. For folks operating within such a mindset, We Have Never Been Woke would certainly be a frustrating read.

Yet, as I’ve detailed at length elsewhere, when social scientists and journalists try to position their work as “interventions,” as Professor Younge seems to wish I had done, this is typically to the detriment of almost everyone involved. As politics, these interventions tend to be deeply misguided. Precisely because of the growing sociological distance between “us” and the people we need to persuade, politicized research and journalism is often received in ways that runs contrary to our expressed goals. Often this politicization actually helps fuel the right-aligned campaigns that Professor Younge is worried about.

Consider: the last time Trump was in power, journalists and scholars dedicated immense effort to pathologizing, demeaning and censoring the Orange Man and his supporters, engaging in lawfare and protests, and framing almost everything they did as #resistance. What were the fruits of these efforts? He’s back in power now, again controlling both chambers of Congress, with an even bigger Supreme Court majority than he had in 2016, and having won the popular vote this time too – all of which have allowed him to tear through our institutions with brutal effectiveness. Meanwhile, symbolic capitalist institutions are hovering near record-low levels of trust, and our preferred political party has reached historic levels of unpopularity, leaving “us” ill-equipped to defend against the current onslaught. There seems to be a clear lesson here if people are willing to see it.

In my view, if we want to understand and address the suffering that fuels the growing influence of political figures like Trump, it’s more important than ever to reckon with the failures of ourselves, our institutions, and our communities. We Have Never Been Woke, I believe, is a good place to start.

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist in the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University. His first book, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, is out now with Princeton University Press.