The Rise and (Likely) Fall of Wokeness

In the past few years, a cluster of books and articles has appeared analyzing “woke” as a cultural phenomenon.1 Even though there is no consensus around its meaning, most analysts agree that it is in essence a mutation within “identity politics.” Woke pursues social justice primarily on the axes of race, gender, and sexuality, much as identity politics has, but in a more militant and intolerant way. Whereas identity politics was always narrower in its ambitions than the more traditional left, it tended to peacefully coexist with both socialist and liberal traditions. Its woke descendant takes a hostile stance to both and is more strident in pressing its social and cultural goals. It is far less hesitant to restrict speech and ascribe motives; it is more skeptical, even pessimistic, about overcoming cultural or racial barriers, and more draconian in narrowing the range of debate.

The rise of woke culture has elicited a great deal of discussion and debate. Much of this has focused on its redefinition of progressivism. Less common has been an analysis of its social roots and institutional propellers. But if the phenomenon is to be properly explained, rather than simply described, some analysis of its genesis and social foundations is needed.

On the Left, woke culture is often presented as an aggressive pursuit of social justice, while on the Right, it is seen as a deformation, a result of the Marxist takeover of civic and educational institutions. But as I will argue, it is neither. In contrast to its left-wing defenders, I will suggest that it expresses a profound narrowing of what counts as social redress; and against the Right, I will show that its success is due to the retreat of the radical Left, not its hegemony. Woke culture is the organic ideology of a narrow elite, drunk with power, and backed by the key power centers of American politics.

The Path Not Taken

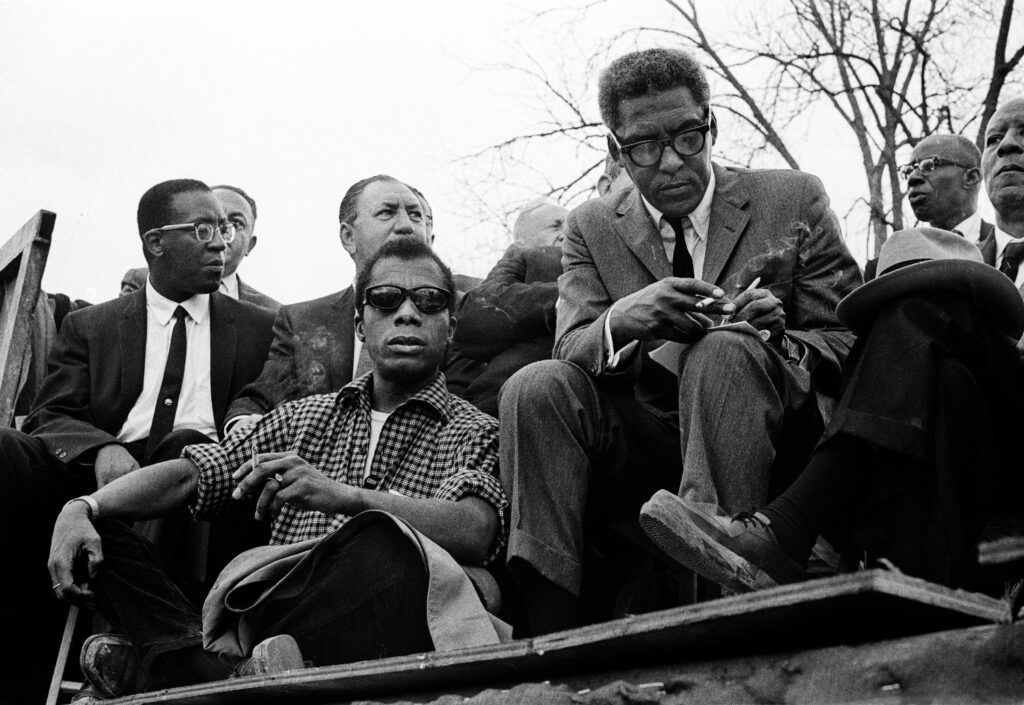

One of the more interesting developments in the scholarship on the civil rights movement is its rediscovery of the movement’s radical and labor-based foundations. A steady stream of historical and social scientific research has shown that while political equality was always a central goal of the movement, its leaders never endorsed separating political rights from economic rights. This flowed from the fact that many of the movement’s most important organizers came out of the socialist and communist traditions. Indeed, for people like Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Tom Kahn, and others, advances in the political realm would be severely restricted if Black Americans remained mired in poverty. Civil rights were therefore taken to comprise merely one component in a larger ensemble of social rights, at the heart of which was a focus on jobs, housing, health care, and education. In other words, the agenda for racial justice would only be effectuated if it was embedded in a wide-ranging economic redistribution.

This focus was not limited to the inner circle around Martin Luther King, Jr. It was an expression of a broad political current that had grown in social influence since the 1930s.2 Led primarily by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and a radical Black intelligentsia around the Communist Party and civic organizations, racial justice was, to a significant extent, identified with the needs and aspirations of working-class Black Americans. It was understood that the extension of formal equality would only have limited significance in their lives if they lacked access to basic economic goods. As King once said, “We know that it isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”3 King and his associates did not fold up the movement once the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. For them, the law was only one step in a longer struggle for the full gamut of rights for Black Americans.

This ambitious social democratic vision of racial justice could only move forward on the strength of its labor and activist base. But by the early 1970s, that base was severely weakened, and then it slowly dismantled over the next decade. In contrast, precisely because of the institutional momentum created by the civil rights movement, a variety of political and social programs did foster a growing professional and elite stratum of the minority population. By the 1980s, there was a significant layer of Black and brown politicians at the local and national levels as well as a substantial growth of minority-owned small businesses—all firmly connected to the Democratic Party.

As the influence of labor waned and that of minority elites increased, there was a natural shift in the goals and ambitions of the racial justice movement. Whereas its earlier incarnation had expressed an agenda tied to the interests of working-class Blacks, by the end of the 1980s ideas of racial justice came to reflect the interests of more elite sections. And because of their proximity to the Democratic Party, it was these interests that were articulated into policy proposals and electoral campaigns.

From Economic Rights to Identity Politics

As a result of the changing political balance, by the time of the first Clinton administration racial justice had morphed into what we now call “identity politics.” This was race politics largely shorn of its earlier commitment to redistribution and economic rights, and more focused on removing barriers to upward mobility for women and minorities. Its focus narrowed to the reduction of disparities within the upper echelons rather than between economic classes. But while this narrower conception of racial justice had become hegemonic by the turn of the century, it had not yet transmuted into what today is known as woke culture. On the one hand it was viewed by many as remedying some of the blind spots and errors of the left, in which problems of discrimination had not been given their due. In this respect, it was seen to be filling out a progressive agenda that still had room for redistributive ambitions, rather than displacing those ambitions outright. Furthermore, even while this incarnation of race politics was critical of a more universalistic stance, it did not yet castigate the latter as inimical to the eradication of racism. In other words, while it was advancing an agenda catering to particular groups—minorities, women—it did not reject political agendas aimed at citizens as a whole or the general population. Rather than an outright rejection of universalism and redistribution, identity politics was often presented as a corrective to universalism’s blind spots.

The delicate balancing of the narrower conception of antiracism with the earlier, grander ambitions of the Civil Rights era reflected the political orientation of the Democratic Party. In the years from the Clinton presidency to the first Obama administration, Democrats moved steadily away from their working-class base, leaning more on suburban and college-educated voters. The increasingly explicit embrace of markets, the retreat from redistributive goals, and the constriction of social justice to antidiscrimination initiatives and culture wars—all of these reflected the party’s greater reliance on its affluent base, to the detriment of its traditional anchor in unions and the working class. But party leaders also understood that even while they were demoting the position of the labor movement in the party, they could not afford to expel it all together. And so some vestigial nods to broad-based economic rights and antipoverty measures remained visible into the Obama presidency.

Sanders, Floyd, and the Elite response

By the end of the second Obama administration the Democrats seemed to have worked out a viable political strategy for the foreseeable future. They had crafted an electoral coalition based primarily on the suburbs and the college-educated population, with a firm foundation in communities of color who were carefully steered by elite minorities into a reliable voting bloc, together with sufficient support from the working class to make the numbers work. All of this was put to the service of a largely neoliberal program, albeit with a few very thin cushions to soften the blow of market forces on the population. The candidacy of Hillary Clinton was to be the apotheosis of this process—a handing of the baton from an African American (man) to a (white) woman, symbolizing the ascension of historically underrepresented groups from the margins to the very apex of power.

The promise of this model was dramatically upended by the explosive emergence of Bernie Sanders in 2016. In his candidacy for the Democratic nomination, Sanders articulated a redistributive agenda, which not only overturned almost all the nostrums embraced by the Democrats since the Clinton era but also elicited a level of mass support nobody in the party had anticipated. Sanders’s foregrounding of economic issues in his campaign threatened to disrupt what the party’s leaders viewed as both a viable and a desirable political model—one that was acceptable to their monied donors and also had a stable electoral coalition behind it.

Clinton, in a now-famous speech of February 16, 2016, she delivered in order to repel the Sanders challenge, wondered if breaking up the banks could address historical issues of discrimination and cultural exclusion. Asking rhetorically if economic measures could ever resolve problems of racial and gender discrimination, she effectively proposed responding to Sanders by resorting to elite identity politics. 4 More subtly, her response signaled a shift in the party leadership’s attitude to economic demands. Whereas its centrist leadership had hitherto tended to at least give a rhetorical nod to redistributive demands, now it chose to calumniate them outright. Rather than being the left-wing of the possible, identity politics was mobilized to foreclose possibilities for more radical change.

Although Sanders lost his bid, his campaign improbably continued to gather steam leading into the 2020 primaries. And his astonishing success in the early phases of the primary elections led to a further consolidation of the party against its populist wing. In what appeared to be a calculated move, all of the candidates save for Biden and Sanders withdrew from the nomination leading into Super Tuesday in 2019. All that was needed then was for James Clyburn, a representative from South Carolina and a major Democratic power broker, to throw his weight behind Biden: He did on February 26, 2020, which announced the fatal alignment of the party’s Black leadership against Sanders’s populist insurgency.

By the spring of 2020, a top priority of the Democratic Party was to sideline its Sanders wing to the greatest extent possible. Indeed, Biden was at least as concerned with distancing himself from Sanders as he was with confronting Donald Trump. It was in this context that the horrific murder of George Floyd transfixed the nation. It was a moment when the pressing need for racial justice was brought to the top of the political agenda, while there still existed a possibility of anchoring that agenda in the ambitions that had steered the civil rights movement. It might very well have been the moment when a movement unleashed by the brutal murder of a working-class Black man intensified the calls to integrate economic rights into a movement for racial justice. But the power balance between the different social forces generated a predictable outcome.

Led by Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, the corporate community threw its weight behind the narrower vision of identity politics the Democrats had been nurturing for some years. Addressing the problem of systemic racism was interpreted to mean an aggressive pursuit of diversity in the professional ranks and more militant policing of the cultural sphere. The momentum that had been gathering for universal redistribution, reaching back to the Occupy Wall Street campaign, rapidly receded. Whereas the Sanders wing of the party had seen its racial justice program as part of a larger panoply of redistributive mechanisms, the party now found a vehicle to separate antiracism from antipoverty and redistribution. Universalistic programs were now denigrated as an explicit rejection of racial justice, rather than a means towards that end.

The Slide from Identity to Woke

This was the moment when, on matters of race, identity politics’ slide into woke accelerated at a dizzying pace. Its components had already been incubating, of course. There had already been a baseline level of anti-universalism, intolerance, cancelation, and professional-class dominance in the years leading up to 2020. To highlight this moment is not in any way to suggest that wokery was invented in that year, but it is difficult to deny that it was catapulted then to a place that it had never been able to occupy before those fateful months. It was at this point that the elite’s capture of the antiracist movement was consummated.

For minority professionals and managers, the windfall was massive. There is still a dearth of systematic evidence, but the research that has been done points in the same direction. The two domains in which professionals benefited the most were probably universities and the corporate sector.5 All this while funding for community colleges, public housing, etc. continued to flounder. Under the banner of antiracism, the floodgates were opened to institutions catering to a Black and brown elite, while the indifference to institutions catering to working-class minorities continued.

The essence of this elite approach to antiracism was to turn attention away from social structures and group relations and toward individuals and psychological attributes. This marked the complete inversion of the perspective that had driven the civil rights movement’s progressive leadership. After the passing of the Voting Rights Act, both Rustin and King had turned their efforts toward achieving massive economic redistribution. But tnow, under the banner of the new antiracism, attention narrowed to two fundamental issues: the degree to which elite institutions were racially diverse and the need to change individual psychology and individual behavior in pursuit of an antidote to “systemic racism.” All of this served to turn attention away from the economic and political power of corporations over their employees and the minority population more broadly, to their internal constitution and culture, especially the diversity of their managerial corps.

So too in education, anxiety around racial justice rapidly translated into a focus on the internal culture of academic institutions—syllabi, degree requirements, the content of scholarship— and the diversity of the managerial corps and faculty. While there were a few voices arguing that the vast majority of minority students were enrolled in community colleges and public universities, where the major issues were funding and retention, these were drowned out by a laser-like focus on affirmative action and faculty diversity, especially in the elite institutions.

All of this amounted to a windfall for the minority professional classes, under the banner of eradicating “systemic racism.” Whatever its moral implications might be, it simply reflected the power balance—not between white and non-white America, but within non-white America. The chain of events leading up to Floyd’s murder created a political opportunity for emerging Black and brown elites, and these capitalized on it with remarkable vigor.

All this was justified by the intellectual culture that prevailed inside academia. The most significant factor here was the weakened condition of liberal nostrums, under the hammer blows of post-structuralism, postcolonial theory, and various forms of race essentialism, all of which were either skeptical of, or hostile to, enlightenment principles. The emergence of anti-enlightenment philosophical trends in the 1980s associated with thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and others, was devastating to the two foundations of modern progressive thought, liberalism and socialism. Steeped in the antirationalism of the post ‘68 philosophies, university culture came to reject those very values that had sustained academic freedom in the post-war era—the commitment to rational debate, the pursuit of scientific progress, and the commitment to free speech. Meanwhile, the remarkable growth of an essentialist approach to race and ethnicity, which downplayed economic divisions within racial groups while elevating the economic and social chasms between them, obscured the fact that woke antiracism was catering to elites within American minorities because the very existence of divisions within races was being downplayed.

The Future of Woke

The slide from identity politics into wokeness had two factors behind it. The first was a kind of elite panic at the emergence of a genuinely populist movement behind Sanders. The second was an understandable anxiousness within the broader culture to address racism after Floyd’s murder. Both of these reasons have by now abated substantially. Most important, the insurgent populist campaign within the Democratic Party today is considerably weakened, if not marginalized altogether. While the Sanders left continues to have some influence, there is no sign of its potentially upending the Democratic electoral coalition. On top of that, even if matters of race continue to be salient in the political culture, they no longer hold the public’s attention the way they did five years ago. This means that the propulsive forces that pushed identity politics into its more militant and intolerant forms are no longer as strong as they were.

There is genuine concern within the Democratic Party and public institutions that the illiberalism and authoritarianism associated with wokeness have fueled a public backlash. And this backlash has empowered political and social groups that have always been hostile not just to wokery but to the entire civil rights agenda. Under the protection of Trump, figures like Elon Musk, Christopher Rufo, Peter Thiel, and others have been emboldened to make inroads under the banner of opposing wokeness into many of the substantive reforms that the movements of the ‘60s actually achieved. Democrats are thus much less committed to promoting woke culture than they were in 2021. With the threat of a populist wave now receding on the political horizon, it is clear that the business community no longer feels it necessary to absorb the personal and organizational costs of wokeness.

With none of the real power centers giving it any real support, it is likely that wokeness will retreat to a more conventional style of identity politics. Certainly in the corporate world the die has been cast to expunge the practices most directly associated with wokeness—DEI, anti-racist training, etc. But even in academia, the elevation of antiracism to a central place in the educational mission is unlikely to continue. Indeed, the more likely outcome is a rollback of longstanding measures, like protections for minorities and the disabled, which conservatives now see as achievable under the banner of antiwokeness. What seems firmly out of reach, given the current balance of forces, is a return to the social democratic version of anti-racism. That will require a great deal more political and organizational change.

Vivek Chibber is professor of sociology at New York University. His most recent book is The Class Matrix: Social Theory after the Cultural Turn (Harvard University Press, 2022)