The Drive for International Justice—and Why It Stalled

Abortive efforts to establish international tribunals to judge war crimes and other great violations of rights following the First World War and again after the Second World War did not get very far. After World War I, proponents of such a tribunal wanted to put Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany on trial for starting the conflict; some also wanted to try officials of Turkey, Germany’s wartime ally, for the Armenian genocide of 1915. Those efforts came to naught because of fears that trying the Kaiser would further humiliate a defeated Germany—and that trying Turkish officials would contribute to the destabilization of the country.

After World War II, the victorious allies succeeded in establishing tribunals that tried defeated German and Japanese military leaders and top civilian officials for waging aggressive war, committing war crimes, and for crimes against humanity. But proposals for a permanent court to try such offenses went nowhere because the quickly developing Cold War made it impossible to reach an international agreement on its establishment.

Nearly a half century elapsed after World War II before it was possible to revive the drive for international justice, following the collapse of the Soviet empire and the end of the Cold War. It was only in the 1990s that it was possible for the United Nations to create international tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda and transform a proposal from Trinidad and Tobago to establish a court to try drug traffickers into the basis for a permanent international criminal court. A treaty establishing that Court was adopted at a conference in Rome on July 17, 1998, with the support of 120 countries; abstentions by 21 countries; and no votes from seven countries (Iraq, Israel, Libya, China, Qatar, Yemen, and the United States).

On April 11, 2002, ten governments ratified the Rome treaty establishing the International Criminal Court. That brought the number of ratifications to 66, six more than required to bring the treaty into effect. Apparently, the governments ratifying that day had wanted to be the ones that would complete that process.

One of the governments that ratified that day was the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It faxed its ratification to UN headquarters. The DRC’s ratification had quick results. At the time, five other African countries had armed forces in DRC territory, fighting each other. Perhaps more importantly, they were also pillaging the country’s rich natural resources. Rwanda and Uganda were on one side of the conflict; Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe were on the other. One of the factors that persuaded the DRC to ratify the treaty, according to my conversations with relevant interlocutors at the time, was its awareness of the impact that this might have on the occupying forces. Under the treaty, war crimes—including pillage—that take place in the territory of a country that is a party to the treaty are subject to the jurisdiction of the Court.

This provision of the treaty was a central factor in the hostility of the United States to the International Criminal Court. The United States had not ratified the treaty before it went into effect and has not done so to this day. The Clinton administration cast one of the small number of votes against the treaty when it was adopted in Rome in 1998, and the George W. Bush administration fiercely opposed the treaty in 2002 when it was ratified. Their concern was that U.S. citizens might be prosecuted for crimes committed in the territory of other countries that were parties to the treaty. The United States wanted prosecutions to be authorized by the United Nations Security Council, which would have allowed any of the five permanent members—the U.S., the United Kingdom, France, Russia, or China—to veto any prosecution.

The treaty did not permit prosecutions for crimes committed before it went into effect. The Court would have jurisdiction for crimes committed from July 1, 2002, onward—less than three months after ratification. During that brief period, all five African governments with troops in the DRC withdrew them. It seems that none of the military chiefs or the heads of government wanted to be the first to be indicted by the International Criminal Court.

Though the Court itself did nothing, and though the Office of the Prosecutor had not yet been established, the mere prospect that it might issue indictments had a major impact in promoting the goals of the treaty. Though conflict continued, with local militias carrying on the struggles underway when the treaty was ratified, the level of harm and the theft of the resources of the DRC declined.

The success of the effort to establish the International Criminal Court derived from the work done during the previous decade by two United Nations-sponsored bodies: the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). As director of Human Rights Watch in 1992, I had initiated a call for the establishment of the ICTY. As international law was understood at that time, the concept of war crimes only applied to international armed conflicts (that has since changed and certain abuses in internal armed conflicts have subsequently been recognized as war crimes). Three internationally recognized states—Bosnia, Croatia, and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia—were parties to the war in Yugoslavia. As the crimes that particularly characterized that conflict were “ethnic cleansing,” a term evocative of the Nazi crimes during World War II, the establishment of an international criminal tribunal appeared to be an appropriate response.

By chance, the call for an international criminal tribunal coincided with the discovery by international journalists of death camps operated by Bosnian Serb forces. This contributed to strong support for the creation of such a tribunal and a resolution by the UN Security Council in May 1993 putting it into effect. It was the first step in providing a mechanism for international criminal justice since the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

At the outset, the ICTY appeared to be a failure. Fourteen months passed before the UN was able to appoint a chief prosecutor. And for a long time, the tribunal had only a single person in custody—a low-level Bosnian Serb former prison guard. But the tribunal gained credibility through the determination projected by its first chief prosecutor, Richard Goldstone of South Africa. He indicted Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić in July 1995, at the same time as the Srebrenica massacre. In 1997, British peacekeeping troops in Bosnia began arresting suspects indicted by the prosecutor. The ICTR, established after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, also got off to a bad start, righted itself, and then issued the first international convictions for genocide.

Over time, both tribunals performed well. The ICTY ultimately obtained custody of all those it indicted except those who had died before they were apprehended. They included significant figures from all parties to the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. It conducted fair trials. Former President Slobodan Milosevic of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia died while on trial. Karadzic, the former President of the Bosnian Serb Republic, and Mladic, the former military commander, are still in prison at this writing. The ICTR obtained custody of most of those it indicted. It also conducted fair trials. It was flawed, however; while all those tried had taken part in the genocide, among those not held to account were leaders of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, which fought against the genocide but also committed significant crimes.

In 1998, the same year that the Rome treaty was adopted, there was another development that had a large impact on accountability for gross abuses of human rights. General Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator who had been deposed in 1990, traveled to London for medical treatment. While there, he was indicted in Spain for crimes committed during his dictatorship and arrested by British authorities for torture that had taken place under his rule. The International Convention Against Torture, which the United Kingdom had ratified, explicitly provides for universal jurisdiction, which permits that courts anywhere in the world to bring to trial those who commit certain especially severe crimes if the alleged criminals are apprehended in their territory. The provisions of the Geneva Conventions dealing with “grave breaches” and the Convention Against Torture explicitly authorize universal jurisdiction. This is also the theory that underlies the establishment of international criminal courts. Pinochet was deported to Chile, where he was to be put on trial.

Though Pinochet evaded trial due to age and infirmity (he died in 2006 at the age of 91), the episode set in motion trials of many of the military officers who had taken part in repression during his 17 years as head of state. By now, hundreds of Chilean officials have been tried and convicted; many of them remain in prison at this writing. An even larger number of military officials have been tried and punished by national courts in neighboring Argentina for crimes committed under military rule in that country, which lasted from 1976 to 1983. They include three generals who served as heads of state, one of whom died in prison. Other Latin American countries in which former heads of state have been criminally convicted by national courts for gross human rights abuses include Guatemala, Peru, and Uruguay.

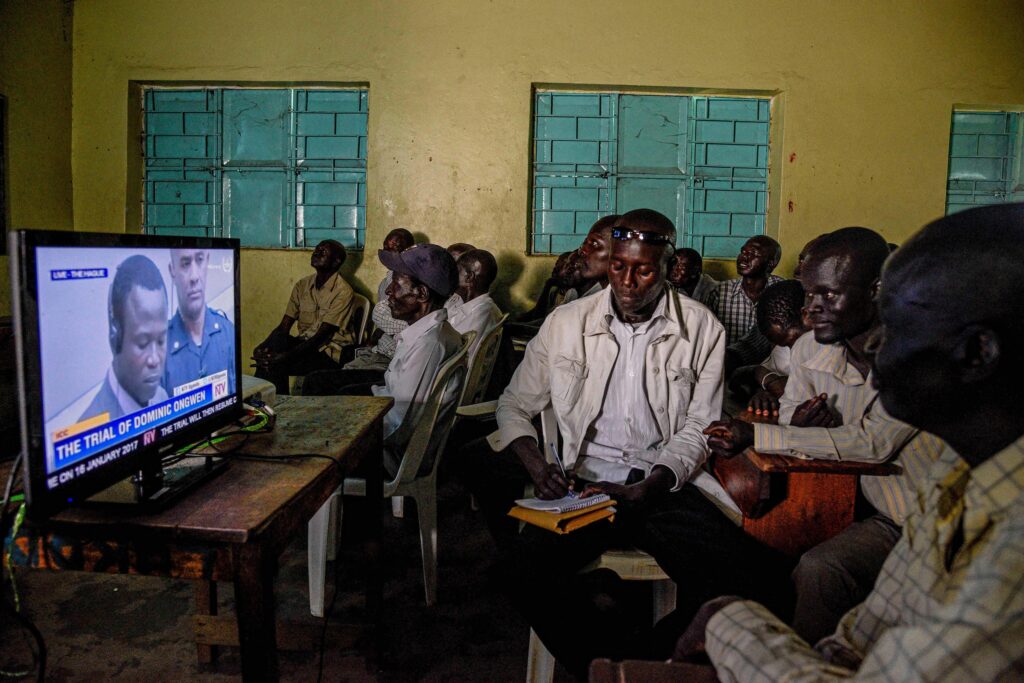

As for the International Criminal Court, many of those active in efforts to promote international human rights who were involved in its creation have been disappointed by its performance. The ICC’s first chief prosecutor was Luis Moreno Ocampo, who had played a leading role in securing accountability for abuses by the military rulers of his own country, Argentina. As ICC prosecutor for nine years, Moreno Ocampo focused almost entirely on attempts to secure accountability in Africa. Thanks to the organizing efforts of No Peace Without Justice, an Italian NGO, and leadership from supporters of the creation of the ICC in South Africa and Senegal, many African governments were among those that had ratified the Rome treaty. Yet leading governments in other parts of the world, including Russia, China, India, Turkey, and the U.S., had not ratified. Other governments that had not ratified included such countries noted for human rights abuses as Myanmar, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, and North Korea. That made it impossible for the ICC’s prosecutor to bring cases addressing abuses in those countries against their own citizens unless the United Nations Security Council authorized them. Given the ability of each of the permanent members of the Security Council to veto such resolutions, there was no hope of launching prosecutions in many of the countries where the most severe abuses took place.

Though these circumstances played a large role in Moreno Ocampo’s focus on Africa, the fact that he seemed to be almost solely concerned with African criminality inspired resentment in Africa. Some of the relatively small number of prosecutions launched by the ICC fared poorly.

One example: the indictment of two important political leaders in Kenya, both of whom served subsequently as presidents of the country: Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto. The latter is the current president. In 2007, there were disputed elections in Kenya which divided the country along tribal lines. Violence ensued, and more than 1,000 people were killed. The death toll could have been much worse. Fortunately, former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan played a very valuable role in negotiating a settlement and stemming the violence.

A subsequent investigation led the ICC to indict Kenyatta and Ruto for inciting the violence. Eventually, those indictments had to be dropped. The ICC failed to arrange protection of witnesses on whom it relied in bringing the cases. Some had apparently been intimidated; others had reportedly been bribed. The prosecutions against Kenyatta and Ruto could not go forward.

On two occasions, the United Nations Security Council referred cases to the ICC. Both involved African countries that had not ratified the Rome treaty: Sudan and Libya. The referral of Sudan took place in 2005 and was based on the killing of an estimated 300,000 dark-skinned Africans in Darfur by Arab tribesmen known as the Janjaweed. Some described the killings as a genocide.

Obtaining the referral by the Security Council was considered a triumph by the international human rights movement. Some had feared that China, the main customer for Sudanese oil, might exercise its veto power. China did not do so, apparently because it did not want to be seen as complicit in a genocide, in keeping with diplomatic concerns regarding human rights before Xi Jinping’s ascent in 2013. There was also concern that the U.S. would veto the resolution of referral because of the Bush administration’s hostility to the ICC.

Originally, the resolution of referral was sponsored by France, which had opposed the U.S. over the war in Iraq. Advocates of the resolution persuaded the government of British Prime Minister Tony Blair to sponsor the resolution, as Blair’s alliance with Bush over the war in Iraq reduced the possibility of an American veto. The most important factor in avoiding a U.S. veto was that John Bolton, an outspoken enemy of the ICC, had been sidelined at that moment. Bolton had been given a recess appointment by Bush as U.S. Ambassador to the UN, where he would have cast the U.S. vote. While his confirmation by the U.S. Senate was being debated, he had to step aside. In his absence, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice determined the U.S. position, and the U.S. abstained rather than veto the resolution. Bolton was not confirmed.

In 2009, Sudan’s President, Omar Al-Bashir, was indicted by the ICC for war crimes and crimes against humanity; in a second indictment, he was charged with genocide. He was the first sitting head of state to be indicted by the ICC. As the crimes for which he was indicted involved the victimization of dark-skinned Africans by Arab militias, one might have expected that Black African leaders of Black African states would have supported the indictment. That is not what happened. By and large, the leaders of Black African states that had ratified the Rome treaty supported Bashir, reflecting the resentment against the ICC that had been developing because of its perceived disproportionate emphasis on punishing African criminality. The African Union denounced the indictment. In 2015, Bashir visited South Africa, a party to the ICC with a legal obligation to enforce its arrest warrants. Though the country’s Constitutional Court held that Bashir should be arrested and turned over to the ICC, the government of President Zuma spirited him out of the country to protect him. More recently, in 2019, Bashir was overthrown, and the new government said that he would be turned over to the ICC. That has not happened. At this writing, Bashir is 80, in detention in Sudan, and reportedly in ill health. The other Security Council referral involved Libya. It took place in 2011, in the early stages of the Arab Spring, when widespread protests against the rule of long-time dictator Muammar Gaddafi took place there. Gaddafi tried to suppress the protests with great violence. His armed forces shot and killed hundreds of protesters, leading to a civil war. Soon after the Security Council referral, the ICC indicted Gaddafi and two of his relatives for the killings. NATO entered the conflict on the side of the rebels. Later that year, as Gaddafi retreated to what had been his hometown, he was captured and killed.

In 2012, Fatou Bensouda of the Gambia succeeded Moreno Ocampo as the ICC’s chief prosecutor. While her tenure was marked by diversification of the Court’s caseload and improved relations with African governments, it did not include major accomplishments. Her attempt to bring charges against CIA officials for crimes committed in Afghanistan (which had ratified the Rome treaty) produced renewed hostility to the ICC by the United States. Under the influence of John Bolton, who served as National Security Advisor in the Trump administration, the U.S. imposed personal sanctions against Bensouda. Those ended when the Biden administration came into office.

One of Bensouda’s initiatives seemed very creative. Myanmar is not a party to the Rome treaty, and it would not have been possible to obtain a Security Council referral given China’s veto power. On the other hand, neighboring Bangladesh is a party to the Rome treaty. Under Bensouda, the ICC commenced a case dealing with the persecution of the Rohingya that forced them to flee Myanmar for Bangladesh, establishing the Court’s jurisdiction as a case of forced expulsion that involved both countries.

In 2021, Karim Khan of the United Kingdom succeeded Bensouda. He dropped the investigation of alleged CIA crimes in Afghanistan initiated by his predecessor. His most notable accomplishment so far has been to secure arrest warrants against Vladimir Putin and another Russian official for transferring Ukrainian children to Russia to be raised as Russians. Among other things, the arrest warrant has limited Putin’s travel. He did not attend a BRICS summit in South Africa because that country would have been obliged to arrest him, as it had been obliged to arrest Omar Al-Bashir and turn him over to the ICC. On such grounds, Putin cannot attend UN General Assembly meetings or other prominent international events. He only travels to places where he is certain he will be safe.

Nearly two years have elapsed since the beginning of the Ukraine war. Many observers of the ICC wonder whether or when additional indictments might be forthcoming. Ukraine has accepted the ICC’s jurisdiction, and so crimes committed on its territory may result in prosecutions.

There is also a question as to whether there will be any indictments involving Israel and Hamas. Israel is not a party to the Rome treaty and does not recognize the jurisdiction of the Court. On the other hand, the Palestinian Authority has accepted its jurisdiction. Some observers expect that the chief prosecutor will indict Hamas for its crimes on October 7 and Israel for its crimes in Gaza. Reportedly, Israel—which controls access to Gaza—is not permitting ICC investigators to enter the territory. It is impossible to know how this might affect the prosecutor’s actions.

In the first decade of this century, a few additional international tribunals were established. These included “hybrid tribunals” jointly sponsored by the United Nations and national governments. The most successful of these to date has been the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which adjudged crimes committed in the civil war that had lasted from 1991 to 2002 and devastated that country.

The two best known defendants were Foday Sankoh, leader of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a guerrilla group notorious for such crimes as rapes and amputations of the limbs of its prisoners; and Charles Taylor, past president of neighboring Liberia, who had taken part in the civil war in Sierra Leone. Sankoh died of a stroke while awaiting trial. Taylor, who had previously been given asylum by Nigeria, was apprehended, put on trial and convicted in 2012 of all the charges against him. He was sentenced to 50 years in prison, which he is now serving in a British prison.

Sierra Leone and Liberia are among the poorest countries in the world and experienced appalling abuses of human rights during the latter decades of the 20th Century. Yet both now seem to be peaceful, functioning democracies. The work of the Special Court for Sierra Leone appears to have made a positive contribution.

In 2016, a tribunal in Senegal established jointly by that country and the African Union convicted Hissène Habré, the former dictator of Chad, for crimes committed during his reign that included the killing of 40,000 persons. Habré had lived in Senegal in exile from Chad for 17 years before his conviction. He was sentenced to life in prison and died while in custody in 2021.

Along with the conviction of Charles Taylor by the Special Court for Sierra Leone, Habré’s conviction of signaled to African leaders that those committing severe abuses of human rights might ultimately be held accountable.

As this review suggests, a measure of accountability for gross abuses of human rights has been achieved in two regions of the world: in Latin America, through national courts; and in Africa, through international tribunals such as the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and the Special Court for Sierra Leone, and the Court that tried Habré. Elsewhere, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has been a great success. On the other hand, despite the operation of the International Criminal Court for more than two decades, there has been little or no accountability for severe abuses in the countries of the former Soviet Union, or in the Middle East, or in Asia. A main reason is that most countries in those regions are not parties to the International Criminal Court. Most of the parties are found in Europe, Latin America, and Africa. Though the ICC has relatively few opportunities to address significant issues in other regions, it has not effectively taken advantage of such opportunities that may be available.

The International Criminal Court has structural shortcomings that are built into the Rome treaty. They reflect the unwillingness of powerful states, including the United States, to allow their own officials, or officials of their client states, to be held accountable for crimes subject to the Court’s jurisdiction. This is the most important reason that the drive for international justice that began with the Yugoslav tribunal’s establishment over three decades ago seems to have stalled. Also, unfortunately, those who have served as the Court’s prosecutors have not always been as effective as partisans of the Court might have wished in their use of the ICC’s limited powers. It is up to the international human rights movement, which was instrumental in launching the drive for international justice, to come up with ways to reimagine and re-energize the struggle to hold accountable those responsible for the most severe abuses of human rights anywhere in the world.

Aryeh Neier is president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations