Bureaucracy Reconsidered

In 2021, during Brazil’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign, a civil servant from the Ministry of Health filed an official complaint, reporting that he was being pressured by Bolsonaro’s political appointees to approve the purchase of overpriced vaccines from a specific pharmaceutical company. He faced criticism and intimidation from the Bolsonaro government for adhering to standard bureaucratic procedures, but the whistleblower’s report triggered a major investigation, which uncovered a corruption scheme involving government allies attempting to misuse public funds through the acquisition of the vaccines. Bolsonaro publicly criticized the Ministry of Health’s career officials, claiming that “technocrats” were sabotaging his administration. The case also contributed to broader accusations regarding Bolsonaro’s pandemic denialism, culminating in a formal complaint filed against him at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

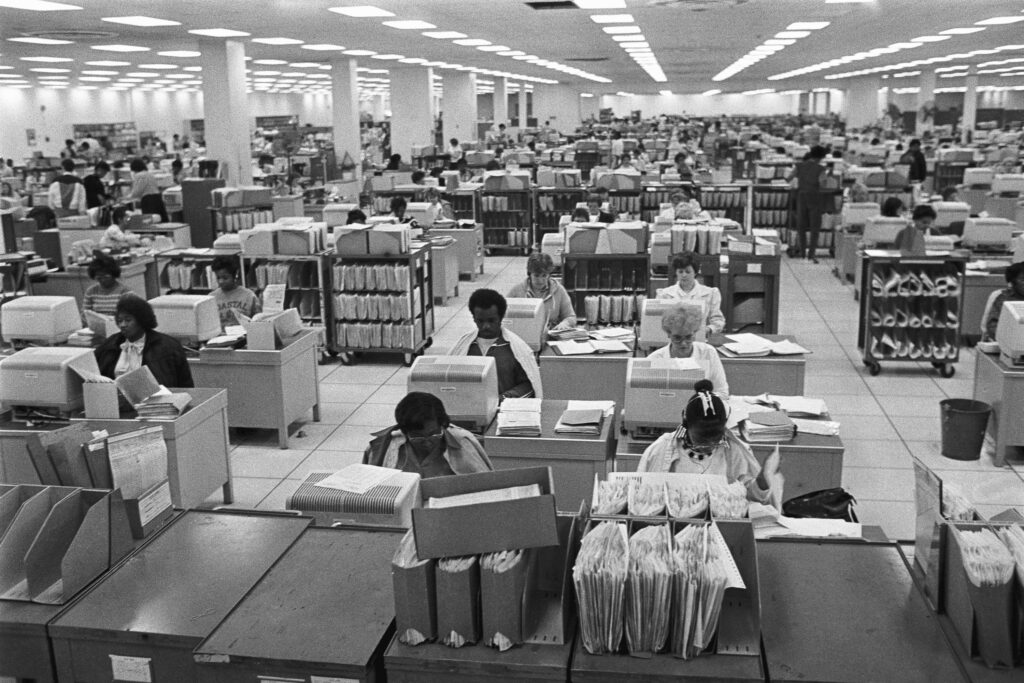

This case – and there are countless more like it – demonstrates the usually hidden and under-discussed role of the bureaucracy: to protect the rule of law and act as a guardian of the state, of institutions, and of democracy. Though it all too often gets a bad rap, bureaucracy is in fact the missing link essential to democracy. Its role extends far beyond enforcing rules and implementing political decisions—it upholds the procedures, norms, historical continuity, and institutional values that sustain the rule of law.

Cases like this also show why the new populist and authoritarian politicians see bureaucrats as enemies. By attacking and undermining bureaucracy1, these leaders are paving the way for democratic erosion, stripping away institutional safeguards and harming society as a whole. After all, stateless is rightless: without the state, society loses its rights2, as there is no way to uphold the rule of law without bureaucratic state capacities3. The increasingly vicious attacks on bureaucracy by contemporary populist leaders are an assault on democracy itself. Despite the frequent denigrations of bureaucrats, they play a crucial role in acting as a safeguard against authoritarian tendencies, shielding democratic institutions from the growing threat of illiberal agendas.

Politicians and Bureaucrats: a trajectory of conflicts

The conflict between politicians and bureaucrats is not new. It has existed since the establishment of civil service systems and stems from the distinct responsibilities that politicians and bureaucrats hold in a democracy. Bureaucrats are professionals working in public administration whose tenures are usually unaffected by elections, while politicians, accountable to the voters, aim to implement agendas. However, politicians must rely on the bureaucrats, who possess the expertise to carry out these agendas, since political decisions do not automatically translate into implementation. The role of bureaucrats therefore is to adhere to established rules and political directives while applying their professional judgment to determine the best way to execute them. This role, when carried out with neutrality regarding personal values, ensures bureaucratic accountability.

The diverging tasks and responsibilities create tensions between bureaucrats and politicians: while politicians temporarily occupy the government (understood as the temporary body of people in power who run the state), bureaucrats are responsible for the state itself (the permanent entity that governs a territory over time). This tension can lead to two types of imbalances4.

The first occurs when politicians reject bureaucratic expertise and attempt to undermine it, opening the door to the politicization of the civil service and the corruption that goes with it. This imbalance was on vivid display in Brazil when Bolsonaro, all of three days into his term, fired some 3,500 civil servants, and continued throughout his presidency to replace longtime bureaucrats with subservient loyalists. The second imbalance arises when bureaucrats fail to fulfill their duty by disregarding legitimate political decisions, pursuing their own agenda, or neglecting their role in advising politicians on the best ways to implement policy. As Don Kettl explains, “There are two ways of being able to undermine new people coming in. One is to do nothing of what they want, so that looks like sabotage. The other is to do everything of what they want. If you do everything that they want, then the people who are in charge fail to be protected from themselves.”

These imbalances raise a fundamental question in democracies: how can bureaucratic accountability to political leaders be balanced with the expertise necessary for governments to effectively deliver on their promises to society?

This tension has always existed within the state, even before the emergence of modern democratic systems. However, as Max Weber observed, it is under democratic regimes that these imbalances become critical. In his analysis of the development of modern states in Europe, Weber emphasized that democracy depends on bureaucracy56 because it requires procedures, rules, and stability—all of which are characteristics of bureaucratic rationality—along with a body of civil servants committed to upholding these principles and ensuring institutional continuity.

However, while democracy needs bureaucracy, Weber also warned that bureaucrats can pose a threat if they disregard legitimate political decisions and establish their own rules, perhaps even by seizing control of the state. There are several solutions to mitigate this risk. First, democracies should establish mechanisms for accountability and oversight to ensure that bureaucrats remain answerable to elected officials. Second, there should be a strong bureaucratic ethos based on a commitment to legality, constitutional principles, and institutional continuity7. As Weber himself wrote in Politics and Government in Germany under a New World Order, the bureaucrat “takes pride in preserving his impartiality, overcoming his own inclinations and opinions, so as to execute in a conscientious and meaningful way what is required of him by the general definition of his duties or by some particular instruction, even – and particularly – when they do not coincide with his own political views.”

At the same time, democratic regimes should protect bureaucrats’ ability to make decisions based on expertise, shielding them from constant political interference that could undermine their impartiality and the stability of institutions. (To that end, many countries have adopted civil service tenure protections that prevent bureaucrats from being arbitrarily dismissed by politicians.) Together these measures help reduce tensions and imbalances, allowing the bureaucracy to exercise its technical role in policy implementation while politicians fulfill their representative function.

Throughout the 20th century, tensions between bureaucrats and politicians flared up in various ways. Between the 1960s and 1980s, for instance, bureaucratic expertise in Latin America was used to justify authoritarian regimes under the guise of technocracy, the belief that technical decisions were superior to democratic ones8. In the 1970s and 1980s, bureaucracy was increasingly perceived as a problem in many Northern countries, prompting neoliberal reforms aimed at reducing the size of the state and introducing business-oriented models in public administration. This global narrative, disseminated through the New Public Management model originally promulgated by academics in the UK and Australia, reinforced the idea that bureaucrats were inefficient and unaccountable. The proposed solution was to “de-bureaucratize” the state in order to restore economic and social development9.

In liberal democracies, imbalances can be corrected by the same system that creates them. When politicians questioned bureaucratic expertise and tried to impose stronger systems of patronage – increasing the number of political appointees – or when they exercised political pressure over bureaucrats – opening space for corruption – they often faced resistance from society as well as the legislative and judiciary branches, as in the case of Richard Nixon’s interference with the IRS, for instance. Similarly, when bureaucrats overstepped their political boundaries, the system imposed corrective measures by punishing them, reducing their power, or increasing oversight mechanisms.

The New Populist Attack on Bureaucracy

The new populist authoritarians arrived into power on a wave of intense political attacks on bureaucracy. “I have zero trust in any government agencies. I have zero trust in our Congress, the Senate, anything,” Trump thundered on the campaign trail. “We have a government that’s not functioning right now. How are you going to gain back the trust of the American people within the government, and are we going to see anybody held accountable?” Javier Milei echoed the American leader: “To manage is to fire the 31,000 ‘ñoquis’ (civil servants who serve no purpose) that we have fired in these first nine months … we must shrink the State to enlarge society.” What sets the current political attacks on bureaucracy apart from those of the past?

Today’s movement against bureaucrats is different because the purpose of these attacks is different. They are leveled not in order to combat inefficiency, but to dismantle the institutions of democracy itself.

History shows that undermining bureaucracy not only weakens its ability to perform essential functions and safeguard social rights but also erodes institutional barriers against authoritarianism and populism. Bureaucracy’s role extends beyond simply implementing policies and regulations; it serves as a fundamental pillar of democracy itself, acting as a guardian of the state10. But this crucial function has been largely underestimated—by both society at large and the field of political science, including classical democratic theory.

The concept of guardians of the state suggests that a professionalized and purpose-driven bureaucracy becomes a body dedicated to “upholding and protecting the principles and institutions of liberal democracy and the rule of law”11. In this sense, bureaucrats do not serve just the government in power. They serve the Constitution12, remaining loyal to the law13 and acting as a “protective belt against attempts at democratic backsliding by populist and illiberal governments”14.

When bureaucrats share a collective professional ethos rooted in republican values and constitutional principles, they function as guardians of institutional memory and democracy itself, creating barriers against the dismantling of the state. For leaders seeking to eliminate these barriers, attacking the bureaucracy becomes a necessary step. These tactics have been observed in the U.S. under Trump15, Brazil under Bolsonaro16 17, Hungary under Viktor Orban18, Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro19, Israel under Benjamin Netanyahu20, Mexico under Andres Manuel López Obrador21, and several other countries (a good overview is Bauer et al, 2020).

Research from various countries shows that populist and authoritarian leaders have used attacks on bureaucracy as a way to expand their power and weaken democratic institutions. To achieve this, they employ a range of strategies22 23, including centralizing decision-making, militarizing public administration24, expanding patronage and political appointments25, cutting resources, altering job stability protections, and carrying out mass firings—often pushing legal boundaries26. These actions create an atmosphere of fear and retaliation, making bureaucrats reluctant to carry out their legal duties with autonomy.

Beyond these strategies, such leaders also rely on populist narratives to justify their attacks, often garnering public support in the process: “The public servant has become a kind of parasite,” Bolsanaro said in 2020. They claim bureaucracy is inefficient, excessively costly, and self-serving, often portraying it as a “deep state” operating in the shadows, an image widely spread by Trump. “They’re destroying this country,” he said. “They’re crooked people, they’re dishonest people. They’re going to be held accountable.”

While these narratives exploit public dissatisfaction with bureaucracy, they conceal a fundamental and deeply consequential truth about the rise of modern populism: bureaucracy is not merely an executor of policies—it is also a bulwark that defends institutions and democracy.

The recent wave of attacks on bureaucracy functions like a process of internal erosion: by weakening it, leaders gradually hollow out institutions from within, crippling their ability to enforce legal and institutional limits. The case of Argentina under Nestor Kirchner illustrates this dynamic. In 2006, his government began manipulating macroeconomic data for political and financial reasons, a scheme that was only possible because the country’s statistical institution had been severely weakened, and its public servants lacked the legal protections needed to resist political pressure. Likewise, Bolsonaro’s 2020 proposal to end civil service tenure protections in Brazil was aimed at eroding bureaucrats’ institutional safeguards and their capacity for resistance. A similar effort is now underway in the U.S. through Musk’s DOGE.

These direct attacks also erode bureaucracy’s ability to appeal. Whether by stripping bureaucrats of their legal protections or by ensuring that institutions capable of contesting decisions are staffed with political loyalists, these tactics create an unprecedented imbalance—one that prevents democratic systems from readjusting internally. This is further compounded by parallel efforts by these leaders to dominate the legislative, judicial, and oversight bodies, thereby dismantling the checks and balances that sustain democratic governance.

By attacking and politicizing bureaucracy, populist leaders erode institutional barriers to the implementation of their agendas. They weaken mechanisms of accountability and oversight, creating an environment where whistleblowing is stifled, institutional memory is lost, reliable data is unavailable, and bureaucratic resistance is neutralized. Over time, they fill public administration with loyalists, expand patronage networks, and execute decisions without internal safeguards. This process results in the loss of public-sector expertise, the erosion of institutional authority, and the dismantling of administrative memory, while replacing meritocratic governance with private interests in state decision-making27.

Of course, bureaucracy can be inefficient, and societies need more agile and effective governance. The state must be continuously improved. Defending bureaucracy does not mean defending its dysfunctions, however. It means advocating for its improvement. If there are problems within bureaucracy, the solution cannot be its destruction. No representative democracy can be sustained without a state equipped with a reliable and competent bureaucracy, as Weber noted over one hundred years ago. Similarly, individual freedom can only exist when there is a state capable of upholding and enforcing rights. As the political scientists Paul Du Gay recently wrote, “Personal liberty has no meaning outside the existence of functioning states that are able to guarantee and enforce individual rights. Personal liberty presupposes social cooperation administered by public officials.”.

An anti-state and anti-bureaucracy discourse that disregards the importance of bureaucracy in defending democracy and the rule of law can, in effect, serve as a tool for dismantling democratic states as we know them. The critical question, then, is this: How can we design models that ensure greater bureaucratic responsiveness and improved performance while simultaneously protecting bureaucracy and reinforcing its role in defending rights and democratic institutions? These are questions that every society committed to liberal democracy and the rule of law should be asking.

Gabriela Lotta is a Professor of Public Administration at Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV, Brazil). In 2021, she was recognized as one of the world’s 100 most influential academics in the field of government by the organization Apolitical.

- Lotta, G., Tavares, G. M., & Story, J. (2023). Political attacks and the undermining of the bureaucracy: The impact on civil servants’ well‐being. Governance (Oxford). doi:10.1111/gove.12792 ↩︎

- Stephen Holmes, ‘Liberalism for a world of ethnic passions and decaying states’, Social Research, 61.3, 1994, p604. ↩︎

- Du Gay, P. (2020). The bureaucratic vocation: state/office/ethics. New Formations, 100(100-101), 77-96. ↩︎

- Abramovay, P and Lotta, G. Democracy on a Tightrope, Politicians and Bureaucrats in Brazil. CEU, 2025 ↩︎

- Weber, M. (2004). The vocation lectures. Hackett Publishing. ↩︎

- ‘Weber, M. Parliament and government in Germany under a new political order’ in Peter Lassman and Ronald Spiers (eds), Weber, Political Writings, Cambridge, CUP, 1994. ↩︎

- Gay, P. D. (2020). The bureaucratic vocation: state/office/ethics. New Formations, 100(100-101), 77-96. ↩︎

- Dargent Bocanegra, E., & Lotta, G. (2025). Expert Knowledge in Democracies: Promises, Limits, and Conflict. Annual Review of Political Science, 28. ↩︎

- Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2022). Politicisation of the public service during democratic backsliding: Alternative perspectives. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 81(4), 629-639. ↩︎

- Yesilkagit, K., Bauer, M., Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2024). The Guardian State: Strengthening the public service against democratic backsliding. Public Administration Review, 84(3), 414-425. ↩︎

- Yesilkagit, K., Bauer, M., Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2024). The Guardian State: Strengthening the public service against democratic backsliding. Public Administration Review, 84(3), 414-425, p. 10 ↩︎

- Heath, J. (2020). The machinery of government : public administration and the liberal state.

Rosanvallon, P. (2011). Democratic Legitimacy: Impartiality, Reflexivity, Proximity. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press ↩︎ - Selznick, P. (1992). The moral commonwealth : social theory and the promise of community. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press ↩︎

- Yesilkagit, K., Bauer, M., Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2024). The Guardian State: Strengthening the public service against democratic backsliding. Public Administration Review, 84(3), 414-425, p. 5 ↩︎

- Moynihan, D. P. (2020). Populism and the deep state: The attack on public service under Trump. Available at SSRN 3607309. ↩︎

- Guedes-Neto, J. V., & Peters, B. G. (2021). Working, Shirking, and Sabotage in Times of Democratic Backsliding: An Experimental Study in Brazil. In M. W. Bauer, B. G. Peters, J. Pierre, K. Yesilkagit, & S. Becker (Eds.), Democratic Backsliding and Public ↩︎

- Story, J., Lotta, G., & Tavares, G. M. (2023). (Mis) Led by an outsider: abusive supervision, disengagement, and silence in politicized bureaucracies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 33(4), 549-562. ↩︎

- Hajnal, G., & Boda, Z. (2021). Illiberal transformation of government bureaucracy in a fragile democracy: The case of Hungary. ↩︎

- Muno, W., & Briceño, H. (2021). Venezuela: Sidelining public administration under a revolutionary-populist regime. Democratic backsliding and public administration, 200-220. ↩︎

- Alon Barkat, S., Gilad, S., Kosti, N., & Shpaizman, I. (2024). Civil Servants’ Divergent Perceptions of Democratic Backsliding and Intended Exit, Voice and Work. Sharon and Kosti, Nir and Shpaizman, Ilana, Civil Servants’ Divergent Perceptions of Democratic Backsliding and Intended Exit, Voice and Work (June 18, 2024). ↩︎

- Dussauge-Laguna, M. I. (2021). ‘Doublespeak Populism’and Public Administration: The Case of Mexico. Democratic backsliding and public administration, 178-199. ↩︎

- Bauer, M. W., Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., Yesilkagit, K., & Becker, S. (Eds.). (2021). Democratic Backsliding and Public Administration: How Populist in Government Transform Bureaucracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- Bauer, M. W., & Becker, S. (2020). Democratic Backsliding, Populism, and Public

Administration. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 3(1), 19-31. ↩︎ - Bauer, M. W., Lotta, G., & de Holanda Schmidt, F. (2024). Bureaucratic militarization as a mode of democratic backsliding: lessons from Brazil. Democratization, 1-19. ↩︎

- https://donmoynihan.substack.com/p/trump-and-musk-are-building-a-new ↩︎

- Lotta, G., Alves de Lima, I., Costa Silveira, M., Fernandez, M., Paschoal Pedote, J., & Landi Corrales Guaranha, O. (2024). The procedural politicking tug of war: Law-Versus-Management disputes in contexts of democratic backsliding. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 7(1-2), 13-26. ↩︎

- Du Gay, P. (2020). The bureaucratic vocation: state/office/ethics. New Formations, 100(100-101), 77-96. ↩︎