We are thrilled to feature in The Ideas Letter 9 an original essay by the venerable law and human rights pioneer, Aryeh Neier. Neier, president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations, is one of the progenitors of contemporary international justice, and he shares here what’s gone well in that space—and what has gone less well—over these last decades. (Stay tuned: in our next issue the first prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, will respond to Aryeh Neier. You won’t want to miss that, or Aryeh’s possible follow-up!)

Our curated content this issue is broad—very broad. We begin with a podcast that breaks down the Pentecostal imagination and tries to understand its global wildfire-like growth. On its heels is a second podcast, this one from the New School in New York City, that smashes the one-dimensional shibboleths about the China-Africa relationship. Ayşe Zarakol in Aeon then looks at the so-called international order pre-Westphalia, from the vantage point of China and Asia, and arrives at some unlikely conclusions.

From there we turn to a piece from Lux that looks at contemporary feminism through a conservative prism. No such thing as a right-wing feminist? Guess again. We follow with powerful remembrances of two legendary historians: Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie (who just passed) and E.P. Thompson (who would have had his centenary this month). We conclude with a Dan Drezner provocation in which he questions whether neoliberalism is actually, really, dead. He thinks not and it’s worth hearing him out.

Our musical selection this issue is a record from the South African bassist, Johnny Dyani, and his quartet sides that were dedicated to his bass/composer hero, Charles Mingus. Dyani spent most of his adult live in exile and died at only 40 in Berlin in 1987.

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

The Drive for International Justice—and Why it Stalled

Aryeh Neier

The Ideas Letter

Essay

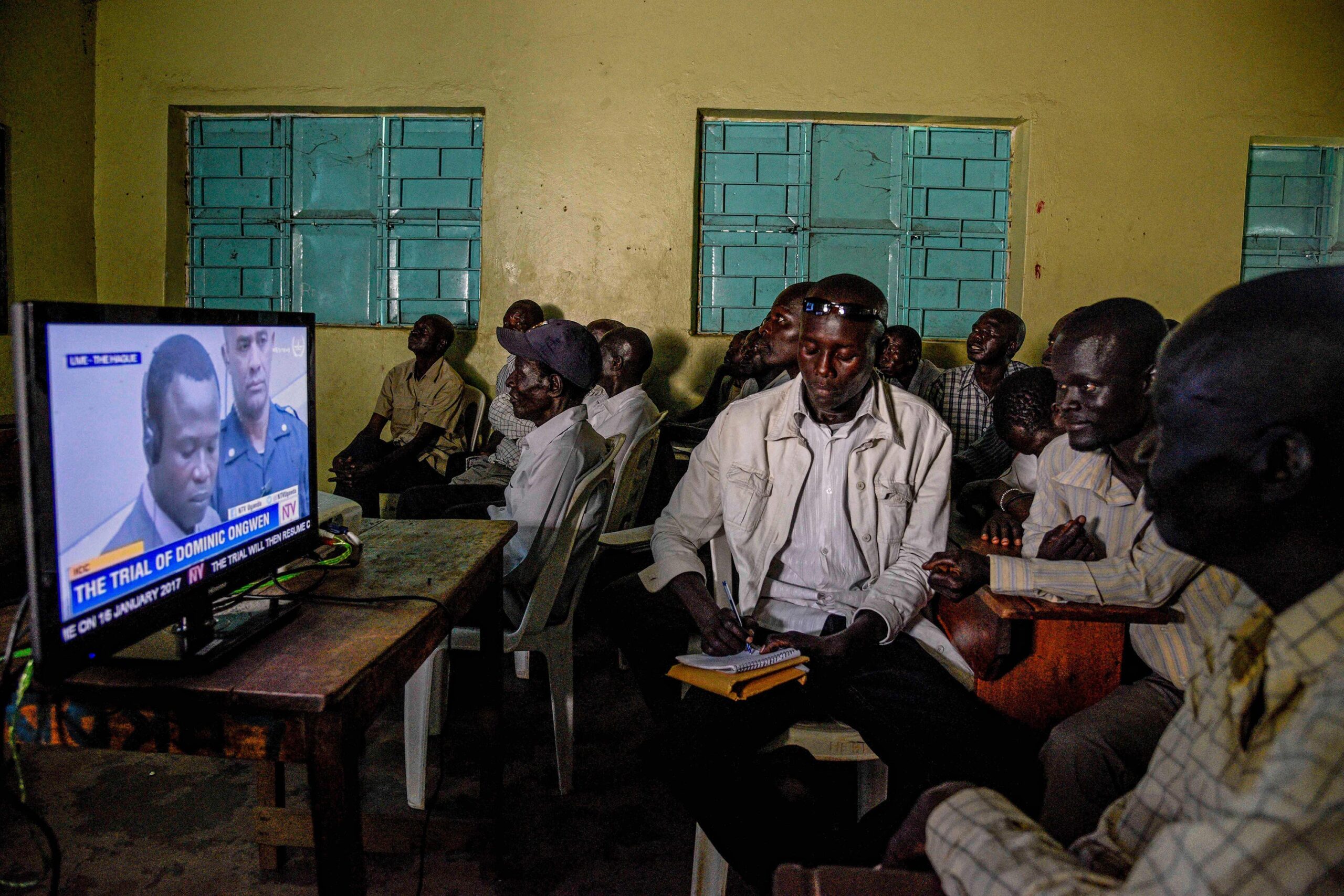

The Cold War derailed efforts to create a permanent international court after successful international tribunals following World War II. The push for international justice truly gathered force in the 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the success of international tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The International Criminal Court has now functioned for 20 years, but has disappointed many of its original advocates, with international power structures impeding potential investigations into gross human rights abuses around the world. During the court’s first decade, prosecution efforts focused largely on African nations—in large part because many African governments were among those that ratified the Rome Treaty, thanks to organizing efforts from civil society and leadership from South Africa and Senegal. Meanwhile, governments from countries noted for human rights abuses, including Myanmar, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, and North Korea, did not ratify the treaty, thereby avoiding the court’s jurisdiction. “There was no hope of launching prosecutions in many of the countries where the most severe abuses took place,” Neier writes, while the focus on African criminality “inspired resentment.”

“The International Criminal Court has structural shortcomings that are built into the Rome treaty. They reflect the unwillingness of powerful states, including the United States, to allow their own officials, or officials of their client states, to be held accountable for crimes subject to the Court’s jurisdiction. This is the most important reason that the drive for international justice that began with the Yugoslav tribunal’s establishment over three decades ago seems to have stalled. Also, unfortunately, those who have served as the Court’s prosecutors have not always been as effective as partisans of the Court might have wished in their use of the ICC’s limited powers. It is up to the international human rights movement, which was instrumental in launching the drive for international justice, to come up with ways to reimagine and re-energize the struggle to hold accountable those responsible for the most severe abuses of human rights anywhere in the world.”

Why are Pentecostals taking over the world?

Elle Hardy in conversation with Nick Spencer

Reading Our Times

Podcast

Pentecostalism is becoming a global religion of the poor, often providing social solidarity networks where no others exist. Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing religious movement in history: it now counts nearly 600 million believers worldwide, comprising about a quarter of the world’s Christians. On this podcast, journalist Elle Hardy discusses her book Beyond Belief: How Pentecostal Christianity is Taking Over the World, looking at the revolutionary origins of the movement in the itinerant preachers of the 19th Century, Civil War-era United States. She describes her visits to Pentecostal communities from Nigeria to South Korea, Traveller communities in the UK, and snake-handling churches in the rural U.S.

“I think it’s really helping people contextualize their lives. One of the other really remarkable things about Pentecostalism, and I think which really contributes to its growth, is its prominence in cosmopolitan cities. People are going to Rio or Los Angeles or London, Lagos and feeling alienated. They’re going there for work. And this is a place to find community, find connections, and find meaning in your life.”

The African Continent and China

Counter-Hegemonic Narratives

New School for Social Research

Video

Scholars and practitioners from the African region and China as well as the U.S. and Europe discuss counter-hegemonic narratives on the theme of relations between the African continent and China. In a context of narrowing space for discussing issues related to China, stances are often oversimplified into pro-U.S. or pro-China positions, leaving little room for nuanced analysis that takes into account historical and class perspectives. In these discussions, Africa is often portrayed as passive, and China is increasingly demonized in mainstream media. The panelists pave the way for more constructive discussions about alternative development paths for African countries and the global South.

“Many individuals enter discussions with preconceived notions influenced by various media narratives, prevalent both in Chinese, Western, and increasingly, African media. Unfortunately, most of these narratives are oversimplified and inaccurate. … It’s crucial to differentiate between China as a state and the Chinese people. China, as a state entity, manifests itself in numerous forms within the China-Africa relationship, including state-owned enterprises, diplomatic missions, aid initiatives, and military presence. On the other hand, there exists a vibrant Chinese civil society in Africa that operates independently from the government. Unfortunately, these distinctions are often overlooked, leading to misunderstandings.”

The Asian World Order

Ayşe Zarakol

Aeon

Essay

Eurocentric accounts of international relations history date the birth of the “international order” to the 17th Century, with the Westphalian Peace that created regional order and then expanded globally. But previous world orders stemming from Asia, starting with the “Chinggisid” world order created by Genghis (Chinggis) Khan and members of his house (13th-14th Centuries), profoundly challenge the Westphalian myth.

“When we study the trajectory of Eastern world orders, we see that structural crises punctuate the end of each order (even if the exact chain of causality is hard to ascertain). The fragmentation of each Eastern world order seems to at least correlate with a ‘general crisis’ that affected large areas of the Northern Hemisphere. …

“Longue durée hindsight allows us to see that political turmoil during these crises (and during the ensuing fragmentation of the existing order) was not really caused by specific great house rivalries or ‘power transition’ (ie, the things international relations most worries about as being corrosive to order), but rather structural dynamics such as climate change, epidemics, demographic decline, monetary problems etc.: ie, the things international relations has not worried about at all until recently. Contrary to the assumptions of the international relations literature about great powers, this history suggests that rivalries by great houses that shared the same understanding of ‘greatness’ in fact strengthened and reinforced the existing world order (even when those rivalries turned violent).”

Tradwives and Femcels

The Women of the New Right Work Hard to Make Marriage Edgy Again

Emily Janakiram and Megan Lessard

Lux

Essay

A growing reactionary feminist movement seeks to undermine women’s rights and autonomy by advocating for traditional gender roles, anti-abortion policies, and a return to pre-modern domestic economies. They argue that men and women have immutable physical and mental differences, and “borrow heavily from the controversial field of evolutionary psychology—evopsych, in internet parlance—which attempts to understand human cognition and behavior through the lens of natural selection and the long history of human adaptation to changing environmental conditions.” They present a seductive narrative that posits these views as a solution to the failures of liberalism, emphasizing the importance of defending women’s bodily autonomy and striving for collective liberation.

“As the liberal consensus disintegrates and we are faced with the brutal consequences of a society that has presented individual choice and consumption as the pinnacle of human liberation and fulfillment, left feminists need to be prepared to take on those who claim to offer respite from the ravages of capitalism in exchange for the freedom of women and girls.”

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and the humanity of history

Alexander Lee

Engelsberg Ideas

Essay

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie revolutionized the study of history by emphasizing the importance of understanding both the deeper socio-cultural structures that shape human behavior over time and the significance of individual events in history. While he was influenced by the Annales school’s focus on long-term historical trends and environmental determinism, Ladurie argued for the necessity of incorporating the “human dimension” into historical analysis, acknowledging the unpredictability and complexity of human societies and events.

“As he worked his way through piles of land registers, tithe books, and tax registers, he realised that history was too varied, too complex—too unpredictable—to be reduced to such a simple heuristic framework. While societies may indeed be shaped by environmental factors, their mentalités are more than the product of their surroundings. Indeed, at times, they may even act against it. And the same was true of events. Sometimes, things just happened—changing everyday life in profound, if unexpected, ways. The key, he realised, was to examine the deeper currents, without losing sight of what was happening on the surface—in other words, to bring the ‘human dimension’ back in. It all came down to how you read the archives.”

See Also

What a legendary historian tells us about the contempt for today’s working class

Kenan Malik, The Guardian

For the legendary British historian EP Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class, “class was ‘not a thing’, or a ‘structure’, but a ‘historical phenomenon’ through which the dispossessed ‘as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against other men whose interests are different from (and usually opposed to) theirs.’”

The Post-Neoliberalism Moment

Daniel Drezner

Reason

Essay

The concept of neoliberalism, which advocates for policies like deregulation and trade liberalization, has fallen out of favor in Washington, D.C. Post-neoliberalism, which emphasizes resilience over efficiency, has gained traction due to events like the China shock and the COVID-19 pandemic, but post-neoliberal policies could produce a Western economy that is both less efficient and less resilient.

“Given the various shocks hitting the global economy over the past decade, it seems intuitively obvious to focus more on resilience. But what if this intuition rests on a false premise? The claims of a ‘post-neoliberal’ paradigm rest on the belief that there is a tradeoff between resilience and efficiency, between strategic autonomy and globalization. But it seems increasingly clear these values are not mutually inconsistent. The best hope for economic resilience might come not from post-neoliberal policies but from neoliberal ones.”