A History of Prejudice

Editors’ note: This essay was adapted from two addresses delivered in the boreal spring, the Kathleen Fitzpatrick Lecture at the University of Melbourne and the Evelien Gans Lecture at De Balie, Amsterdam.

Over the last 100 years, the struggle against antisemitism and the struggle against racism have at times appeared inextricably connected, firmly allied in a single fight against bigotry. Today, it is the disconnections that appear most visible.

The standoff is now stark, thanks to divergent responses to Oct. 7, 2023 and its aftermath—to Hamas’s attack on Israel and the killing of civilians and hostage-taking, and to Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza and the death, displacement, and privation it has brought. These events have not only had grievous consequences for Palestinians and Israelis; they have also been divisive globally. And they have accelerated and amplified a split between anti-racism and anti-antisemitism that was already advanced.

For some, the attack of October 7 was an act of specifically antisemitic terror. “What is this, some pogrom in Lithuania?” asked Amit Halevi, the chairman of Be’eri, a kibbutz that lost 10 percent of its civilian population in the massacre. Others have drawn connections between October 7 and the Holocaust, finding “the antisemitism of extermination” expressed by Hamas today, as it was by the Nazis before.

Yet much of the anti-racist Left presents these events in a different key. In Britain, the Palestine Solidarity Campaign reacted immediately, on Oct.7: “The offensive launched from Gaza today can only be understood in the context of Israel’s ongoing, decades long, military occupation and colonisation of Palestinian land and imposition of a system of oppression that meets the legal definition of apartheid.” Amnesty International denounced Hamas’s attacks on civilians, but it located the roots of the violence in Israel’s 16-year blockade of Gaza and the discriminatory system it imposes on all Palestinians. By invoking apartheid, these groups, among others, affiliate Palestinian resistance with the resistance against the former racial state in South Africa. This war of words pits Hamas’s genocidal antisemitism against Israel’s reinvention of apartheid, a crime against humanity.

These conflicting visions also divide responses to Israel’s assault on Gaza. With heavy symbolism, it was the government of post-apartheid South Africa that brought the charge of genocide against Israel before the International Court of Justice late last year. Demonstrations across the globe have accused Israel of war crimes, ethnic cleansing and genocide. In court and on the street, Jews and Israel, the Jewish state, no longer feature only as victims of a foundational genocide perpetrated by the Nazis and their allies, but are accused of perpetrating a genocide of their own.

Israel’s ministers and mainstream diaspora Jewish organizations, for their part, focus on antisemitism. The South African Jewish Board of Deputies issued this statement in January: “Global Jewry are united that the charges have at their root an antisemitic worldview, which denies Jews their rights to defend themselves.” Israel’s leaders and mainstream Jewish organizations elsewhere regard the demonstrations against Israel and in solidarity with Palestinians as expressions of rising antisemitism—and of indifference to the genocidal threat they identify not only with Hamas but also, more broadly, with the Palestinian demand for freedom “from the river to the sea.”

In short, some Jewish people are locked in a conflict with others who identify themselves as anti-racists. The disagreement is bitter. It is no trivial matter to tell someone they are an antisemite or a racist. And the conflict worsens as it reverberates in myriad local contexts. Since October 7, there has been a sharp spike in recorded antisemitic incidents in many countries; Jewish leaders have called this surge unprecedented. But others caution against scaremongering and suppressing protests in support of the people of Gaza and other Palestinians.

How did anti-antisemitism come to be separated from anti-racism in this way? To answer this question, first we must ask what we mean by “antisemitism” and “racism.”

As the historian David Engel points out, antisemitism is a way for people to group and categorize a variety of phenomena that they believe share a quality and so belong together. When they call something “antisemitic,” they are not holding a mirror to the world so much as interpreting it.

Because “antisemitism”—as well as “racism,” for that matter—are ways of comprehending the world, it follows that these concepts have a history: There is a moment when they came into use, after which they evolved. Antisemitism did not mean in the 19th century what it has come to mean today. So, too, the relationship between anti-antisemitism and anti-racism hinges on the history of these terms, and it changes as their meanings change.

Jewish people have experienced adversity and antipathy for millennia, but it was only in the second half of the 19th century that the terms “antisemite,” “antisemitism” and “antisemitic” were coined. And it was only after 1880 that the new terminology began to circulate widely, first in Germany and then across the globe. In 1879, Wilhelm Marr created the League of Antisemites. Jews in Germany had been granted equal rights, finally, in 1871, and for Marr and others this was a grave error. To protect Germans and German culture from domination by Jews, they called for an end to equality for Jews in the Reich. This was the onset of the antisemitic political movement.

Jews and their allies, in turn, swiftly adopted the terms “antisemitism” and “antisemites” to refer to Marr’s self-proclaimed movement. In a long essay published in 1910 in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Lucien Wolf contrasted the modern anti-Jewish campaign in Germany with pogroms in Russia in the 1880s. The latter were not an example of antisemitism, he argued, but “essentially a medieval uprising” animated by “religious fanaticism” and “gross superstition.” Just before World War I the German-Jewish Zionist Arthur Ruppin reflected, “the anti-Semitic movement grew up on German soil; it is almost as old as the enfranchisement of the Jews.” In other words, he believed antisemitism reached back no further than the late 19th century, and the campaign against antisemitism was a campaign for equal rights for Jewish people.

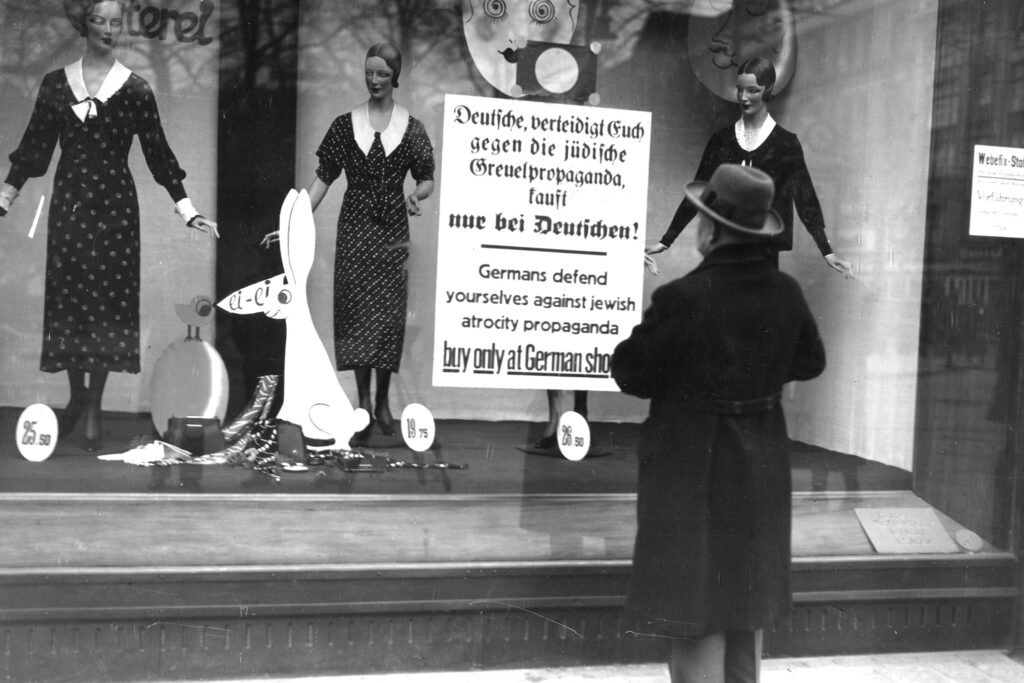

Within two decades the Third Reich in Germany would commence a radical assault on the rights of Jewish people. Between 1933 and 1939, the Nazi regime issued 400 decrees and regulations to that end, beginning in April 1933 with the Jews’ exclusion from the civil service. Then in 1935, the Nuremberg Laws formally excluded Jews from citizenship. By 1941, the Nazi regime had embarked on its attempt to exterminate Europe’s Jews. The assault on the rights of Jews had reached the right to life itself.

And what of “racism”? The term can be traced to the beginning of the 20th century, but it was only after the triumph of National Socialism in Germany that it became widely used in the English language—to refer to the biologically based doctrines promoted by the Third Reich.

The first book in English reportedly to include the word in its title—Racism, in fact, was its title—was written by Magnus Hirschfeld in German, translated, and published posthumously in 1938. Hirschfeld examined the theories underpinning the doctrine of race war proclaimed by the leaders of the Third Reich. He regarded those as irrational. He wrote that he could see throughout Europe and the United States the “germs” of what in Germany had turned into “paroxysms of racism.” Racism, Hirschfeld argued, was based on a myth whose force conquered the heart not the head. He hoped to combat the mysticism of racial theories by subjecting them to unprejudiced scientific scrutiny.

This critique of race was integral to the project of reconstructing the world after 1945. In particular, it was a task undertaken by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO’s constitution stated that “the great and terrible war which has now ended” had been made possible by “the doctrine of the inequality of men and races” and “ignorance and prejudice.” By taking the Nazi regime as the paradigmatic case, UNESCO helped to establish an influential postwar understanding of racism as something driven by bad ideas. Its official statement on race—entitled “The Race Question”—published in 1950, held that biological races were real but also that there was no evidence to connect these differences to the mental characteristics and cultural achievements of different human groups. UNESCO’s approach carried the hope that racial prejudice and discrimination would collapse once the erroneous nature of racial doctrines had been exposed.

At that point, the struggle against antisemitism and the struggle against racism appeared as twin fronts in a single war. Both fights were seen as reactions to prejudice, and prejudice was based on myth. This interpretation reached far beyond the United Nations. It appeared, for example, in the writing of the Black American intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois. In his 1952 essay on “The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto,” Du Bois reflected on his shocking encounters with European antisemitism. He concluded that “the Negro problem”—namely, “the problem of slavery, emancipation, and caste in the United States”—was not “a separate and unique thing” but one part of a “race problem” that was “a matter of cultural patterns, perverted teaching and human hate and prejudice.”

And if the problem of prejudice lay in pseudo-science, and in an aversion to difference to which some personality types were particularly vulnerable, then a remedy could be found in good science, education and the promotion of equality before the law. The fruits of the Black-Jewish allyship were visible in the American civil rights movement. In Britain, Holocaust memorialization in the 1960s was the occasion for Jewish leaders to voice support for legislation designed to counteract discrimination against immigrants from the Caribbean and South Asia.

For a time, support for Zionism and a rose-tinted perception of Israel sat comfortably within this conception of anti-racism. The leaders of diaspora Zionism presented the nascent Jewish state as a step forward not only for Jews, but for humanity as well, compatible with the reassertion of equal rights that would make the world safe for all. Cosmopolitanism was the dominant sensibility among these diaspora Zionists. The leader of the American Jewish Committee, Jacob Blaustein, once proclaimed, “the rights of Jews will only be secure when the rights of peoples of all faiths are secure.” How the Jewish state would deal with its own minorities was a vital question. In a 1952 speech, Maurice Perlzweig, a senior official of the World Jewish Congress, stated eloquently that, “Just as the liberty of every individual must in justice be limited by the equal right of other individuals, so the emancipation of a national group must be limited by the right of other national groups, however small or feeble.” In 1967, he claimed that Israel had passed this test: “every Arab citizen, as an Israeli citizen, has exactly the same rights as every Jewish-Israeli citizen.”

In these postwar decades, support for Zionism melded with opposition to antisemitism and racism. This union stood on three legs. First, racism was rooted in a collection of myths epitomized by the treatment of Jews under the Nazi regime. Second, equal rights held the remedy for racism. Third, Zionism was a liberal doctrine and a necessary response to endemic antisemitism: It was part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Over the next decades this formation unraveled. Part of the explanation is that the image of Israel projected by liberal Zionists in the diaspora was partial and misleading. Perlzweig claimed in 1967 that Israel’s Arabs enjoyed perfect equality, but in truth until a year earlier they had lived under martial law. The very foundation of Israel, moreover, had led to the Nakba and the displacement of roughly 700,000 people—about one half of the Arab population of Mandatory Palestine.

The Nakba forged the demographic conditions that allowed the new state to be both Jewish and a democracy: The refugees were not allowed to return, which created an overwhelming Jewish majority in the new state of Israel. After the Nakba came dispossession. In 1949, just 13.5 percent of the land in Israel was in Jewish hands; by the 1960s, the figure was 93 percent. The state expropriated between 50 percent and 60 percent of Arab-held land in Israel.

Yet the displacement and the dispossession of Palestinians alone do not explain why the ties between anti-antisemitism and anti-racism came undone. These facts predate the unraveling. It is only in the last two decades or so that these features of Israel’s past and present have mobilized anti-racists globally. Two other things also changed: the conception of racism and the conception of antisemitism.

The meaning of racism was transformed by anticolonial and postcolonial intellectuals and political leaders in the middle decades of the century. Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, opened his 1963 book Africa Must Unite with a quotation from Capitalism and Slavery (1944) by Eric Williams, a historian and a future prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago: “Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” This conception of racism pivoted away from Nazism and the Holocaust: Racism was not caused by bad science but by capitalism and state power.

In a 1960 address, Nkrumah called on the UN General Assembly to lead the fight against imperialism and protect the right to self-determination of all peoples. Over the next two decades anticolonial nationalists turned the UN into a platform for the international politics of decolonization. In 1975, the UNGA passed Resolution 3379, in which it “determined” that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” The resolution passed, by 72 votes against 35 (with 32 abstentions), not only because of votes amassed by the Soviet Union mobilizing its allies and friends, but also because by then racism had come to be associated with colonialism.

The moment brought two sorts of anti-racism into open conflict. Israel’s ambassador to the UN, Chaim Herzog, repudiated the resolution by vindicating Jewish nationalism and its cosmopolitan character. Zionism, he said, was a Jewish liberation movement, analogous to the liberation movements that animated people in Africa and Asia. It was “the embodiment of a unique pioneering spirit, of the dignity of labour, and of enduring human values,” and it “has presented to the world an example of social equality and open democracy.”

Meanwhile, in the United States the idea of “institutional racism” was proving as divisive as the identification of racism with colonialism was at the UN. The term was made famous in the United States by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton in their book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, published in 1967. A year earlier, writing in the Massachusetts Review, Carmichael had drawn a distinction between individual racism and the lack of proper food, shelter and medical facilities that caused 500 Black babies to die each year. What he called “the Negro Community” of the United States was the victim of “white imperialism and colonial exploitation.” This materialist and structural understanding of racism challenged the Black-Jewish allyship based on a common ideological foe. James Baldwin also made this clear in a coruscating essay published in the New York Times, in 1967 as well, under the title “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White.” Baldwin did not endorse Black antisemitism, but he laid bare its economic core: Jews shared in the material security enjoyed by white people in the United States.

Although such tensions were most vivid and most vividly expressed in the U.S., they extended globally. And this reorientation of the concept of racism had far-reaching consequences when it interacted with the politics of Israel/Palestine. The UNGA “revoked” Resolution 3379 in 1991, at the end of the Cold War—but a decade later the UN was dominated again by the claim that Zionism is racism. The 2001 United Nations World Conference Against Racism held in Durban, South Africa, marked a rupture between the politics of anti-antisemitism and international anti-racism.

Two contentious issues surfaced at the Durban conference and an attendant NGO forum: reparations for slavery and colonialism, and the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. These were connected. The debate over reparations dealt with the legacy of colonialism and racism past; the debate over Israel/Palestine turned on whether the conflict was about racism and colonialism in the present. By now, the politics of race clearly had been transformed: For an increasingly influential global bloc, Israel and its supporters were part of the problem.

The conference took place in the shadow of the Second Intifada, which had broken out at the end of September 2000. The final declaration from Durban named Palestinians as victims of racism and racial discrimination. The NGO declaration and plan of action submitted to the conference went further, calling Israel a perpetrator of war crimes, ethnic cleansing and apartheid. The United States and Israel left the conference when they realized they could not be sure the Israel-critical language would be removed. The walkout also prevented substantive discussion of slavery and reparations. Some Black Americans argued that the U.S. government displayed then more concern for its ally Israel than for the suffering of African Americans, its own people.

Jewish civil society was filled with alarm, not least on account of the antisemitism in evidence at the NGO forum: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was for sale openly at the stand of Arab Lawyers Union. The Durban conference illustrated the vitality of anti-Jewish narratives and stereotypes in the context of anti-Zionism. It also demonstrated how the reconceptualization of racism as a product of colonialism led Israel’s victims and enemies to place the country in the racist camp—a point the U.S. positions on both Israel and reparations for slavery only made more vivid.

Israel and Jewish NGOs responded to this moment with a series of initiatives aimed at shifting what was still the conventional understanding of antisemitism: discrimination and prejudice against Jews. Back in 1975 the Israeli foreign minister, Abba Eban, had foreshadowed this development. A week before Resolution 3379, he had written, “There is, of course, no difference between anti-Semitism and the denial of Israel’s statehood.” After the Durban conference, Israel and Jewish NGOs developed and resolutely promoted a novel conception of antisemitism.

In 2004, Natan Sharansky, a former Soviet dissident and the Israeli minister for diaspora affairs, proposed a “3D test” to distinguish antisemitism from legitimate criticism of Israel. In this view, attacks on the state of Israel that involved demonization, double standards or delegitimization were antisemitic. Once, the struggle against antisemitism had taken aim at attacks on the rights of Jewish people, but now it was also aiming to protect a state—Israel—from political attack.

Another initiative, perhaps the most significant one, was the working definition of antisemitism produced in 2005 by Jewish NGOs and academics in collaboration with the European Union Monitoring Commission on Xenophobia and Racism (EUMC). The definition itself was empty: Antisemitism is “a certain perception of Jews which may be expressed as hatred of Jews.” The largest part of the text was taken up by examples that, “taking into account the overall context,” could be considered instances of antisemitism. Presented in two lists, these dealt with antisemitism either as conventionally conceived or as manifestations of protest over Israel; they included “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” by “claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavour” and “applying double standards” to Israel, or standards not applied to other democratic nations. These were variants on Sharansky’s initiative, and like his 3Ds, they extended the scope of antisemitism beyond protecting the equal rights of Jewish people to encompass protection for the Jewish state.

Two other features of the EUMC working definition of antisemitism were significant. First, it did not place the struggle against antisemitism within a framework of general principles that safeguard the rights of minorities more broadly. Antisemitism was sui generis, and the fight against it, too. Second, the working definition rapidly gained support among mainstream Jewish institutions, particularly in Europe. They insisted it was for Jews themselves or their representatives in mainstream communal organizations and NGOs to identify and define antisemitism.

The EUMC working definition proved central to the reconceptualization of antisemitism in the early 21st century. Rebranded (and slightly edited) in 2016 by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), today it is the definition favored by mainstream Jewish communities the world over, as well as 43 states, hundreds of governmental and inter-governmental institutions, and civil society organizations. And as documented by the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies, among others, this definition has been used to delegitimize points of view critical of Israel or in support of Palestinian rights and to undermine academic freedom and freedom of speech.

Use and abuse of the IHRA working definition, especially in Europe and the United Kingdom, prompted the formulation and publication in March 2021 of “The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism.” Created by academics (including me) in fields such as Jewish history, Holocaust studies and Middle East studies, the JDA has the support of 350 scholars. It provides a functioning definition of antisemitism: “discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish).” It acknowledges that opposition to Israel’s actions sometimes generates antisemitic speech and violence and that it sometimes targets Jews outside Israel. Crucially, however, the JDA does not align the struggle against antisemitism with the political interests of the state of Israel, and it opens a critical space for debate: It helps us distinguish between cases when criticism of Israel qualifies as antisemitism and when it does not. One might oppose, or support, the movement to boycott Israel, but, as the JDA proposes, the movement itself is not inherently antisemitic.

As the contest between the JDA and the IHRA working definition shows, antisemitism is indeed a concept, and it gives rise to debates that cannot be resolved empirically. Different conceptions of antisemitism reflect different principles, distinctive intellectual positions and divergent policy preferences. When we call actions antisemitic (or racist), we are not simply classifying those actions; we are declaring them unjust and unacceptable. We are not only describing the world, we are interpreting it—and we are seeking to change it.

One aim of the JDA was to bridge the divisions that had developed between the politics of antisemitism and anti-racism and the Left more generally. Its preamble states, “while antisemitism has certain distinctive features, the fight against it is inseparable from the overall fight against all forms of racial, ethnic, cultural, religious, and gender discrimination.” The declaration also invokes a tradition of anti-racism founded on cosmopolitan principles, citing, for example, the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

Neither the JDA nor the sort of politics its represents predominate today. The obstacles to change are formidable. Many conceptions of racism cast the experiences and perspectives of minoritized groups as decisive, creating a zero-sum dynamic between mainstream Jews (and their allies) and Palestinians (and their allies). Israel’s policies and practices are polarizing and isolate from the anti-racist movement those Jews who identify with Israel, even if some do so with a heavy heart. Another obstacle is the strain of antisemitism that surfaces within the Palestine solidarity movement and the movement’s failure to repudiate those responsible for it.

But the cosmopolitan principles that inspire the JDA’s approach provide a way forward; they offer a reference point against which anyone can check their demands, their behavior and language. It is this perspective, still more than the document itself, that is significant. And on this front, there are signs for hope. In 2013, a report by the Pew Research Center found that 69 percent of respondents among American Jews felt “very” or “somewhat” attached to Israel; by 2020, the figure had fallen to 58 percent. By then a bare majority in the 18–29 age band of respondents said they felt “not too” or “not at all” attached to Israel. The Institute for Jewish Policy Research in Britain has reported similar tendencies. At the very least, there is a growing gap between the Israel-focused politics of anti-antisemitism promoted by mainstream Jewish leaders and the preferences and choices of many Jewish people.

Over the last decade, Jewish groups in the U.S., the UK, and globally have emerged that translate cosmopolitan ideals into political activism, rebuilding and reimagining allyships. In my own experience teaching trade unionists, political activists and others over the past six years, the great majority are eager to express support for Palestinian rights without lapsing into anti-Jewish racism and are keen to learn how to avoid that mistake.

The union of anti-antisemitism and anti-racism after World War II was contingent, however natural it may have seemed at the time. Is their disunion today contingent, too?

The marriage fell apart as it became clear that the roots of racism in enslavement and colonialism, as well as its consequences, were often different from the sources and manifestations of antisemitism. Israel’s continuing disregard for Palestinian rights helped transform these differences into a debilitating wound. The old idea that antisemitism and racism were two parts of the same problem was no longer compelling, even when it remained partly true. Today, any broad-based political reunion of anti-antisemitism and anti-racism will have to recognize these essentials and bridge them. Growing numbers of activists and advocates are striving to do just that—aiming to forge not unity but a coalition based on realism and cosmopolitanism.