In our last issue, Evgeny Morozov traced the ascent of a new oligarch-intellectual class. In Ideas Letter 38, David Klion looks at a class in steep decline: liberals. One of the most trenchant observers of the increasingly benighted US political scene, Klion is finishing an eagerly anticipated book on neoconservatism’s legacy.

Brazilian political scientist Gabriela Lotta’s injunction to take bureaucracy seriously chimes with Klion’s analysis. Lotta argues that it’s been a serious error to ignore the bureaucracy’s integral function in a democracy as a repository of expertise. The current assault on bureaucracies in the US, Argentina, and her own Brazil confirms her position.

Lincoln Mitchell was once part of that state apparatus that Trump is dismantling. As Chief of Party at the National Democratic Institute in Georgia, Mitchell had a front-row seat (in anthropological parlance he was a ‘participant-observer’) to the country’s so-called Rose Revolution in 2003-4. He reflects on that moment in the current conjuncture where democracy and autocracy are ensnared in a fight for supremacy.

Our curated section commences with Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s optimistic ideas about re-legitimating liberalism. Writing for The Baffler, Malcolm Harris applies his inimitable analytic skill to show what their warmed-over centrism leaves out. We next turn to our great friends at Africa is a Country for an arresting podcast on the long view of Ghanian political history from Nkrumah to the present day.

In a learned review essay for Modern Intellectual History, Lars Cornelissen historicizes and theorizes neoliberalism’s putative decline. Focused prospectively, Jonathan White follows by examining the need for democratic politics to envision the future worth fighting for. For White, this is a necessary element in an age when all futures appear irredeemably foreclosed.

Last, Jürgen Habermas, the grand old once-upon-a-time Frankfurt School philosopher, turns 96 later this spring. Matt McManus reviews a trio(!) of new books by Habermas. What the legendary philosopher thinks about the present moment may surprise.

Our musical selection for Ideas Letter 38 is the great Sam Cooke. He was killed before he turned 34 yet left us with some of the most velvety soulful music. Here he is on his most somber record, Night Beat, singing “Trouble Blues.”

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

The War on the Liberal Class

David Klion

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Liberalism is under existential threat not only ideologically but materially, as the traditional liberal “New Class”—comprising professionals in academia, media, government, and culture—is systematically undermined by a rising right-wing elite. This new oligarchic class is dismantling liberal institutions and replacing them with parallel structures that reward loyalty and reaction over expertise and critical thinking, accelerating a broader decline in literacy, institutional authority, and civic life.

“Taken together, the right’s attacks on the liberal New Class can be seen as a unified project to diminish its influence, disassemble its institutions, and immiserate the people with the educations and temperaments to work in those institutions. This project exacerbates long-term trends that not only precede Trump but may have helped bring him to power. … The institutions of Cold War liberalism—which, whatever their flaws, helped create a mass of literate Americans among whom intellectuals and experts held prestige and wielded influence over several generations—are all in perhaps terminal decline. Liberals face the threat not just of isolation but also of irrelevance, or even extinction.”

Bureaucracy Reconsidered

Gabriela Lotta

The Ideas Letter

Essay

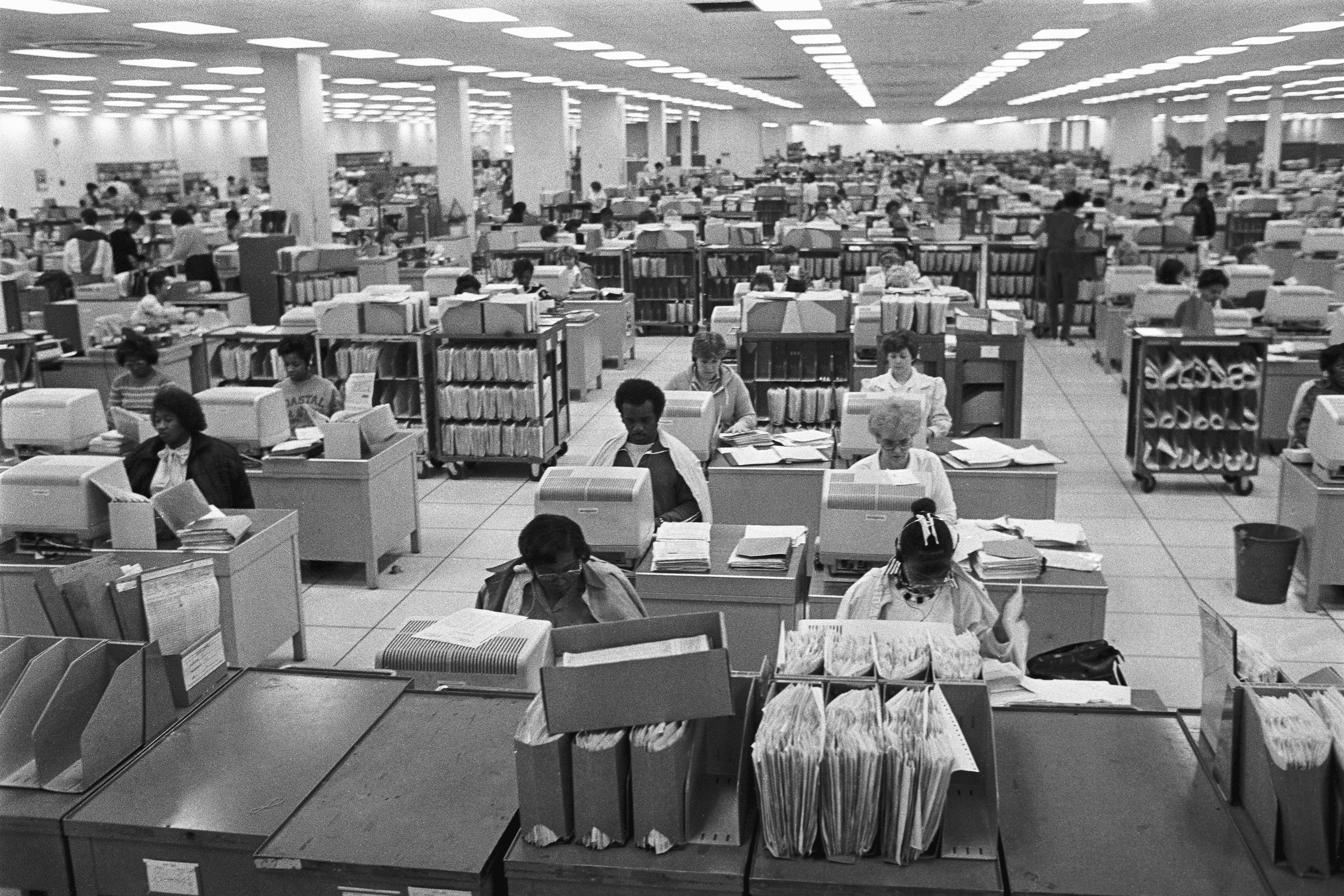

Lotta argues that bureaucracy is an essential yet overlooked pillar of liberal democracy, serving not only to implement policies but also to uphold the rule of law, ensure institutional continuity, and protect democratic norms—especially against authoritarian threats. Tensions between politicians and bureaucrats are inevitable: while bureaucrats ensure technical expertise and impartiality, politicians often seek to undermine or politicize the civil service to advance personal or partisan agendas. The rise of populist leaders has intensified these attacks. The goal? To dismantle democratic checks and balances from within.

“Today’s movement against bureaucrats is different because the purpose of these attacks is different. They are leveled not in order to combat inefficiency, but to dismantle the institutions of democracy itself. … History shows that undermining bureaucracy not only weakens its ability to perform essential functions and safeguard social rights but also erodes institutional barriers against authoritarianism and populism. Bureaucracy’s role extends beyond simply implementing policies and regulations; it serves as a fundamental pillar of democracy itself, acting as a guardian of the state. But this crucial function has been largely underestimated—by both society at large and the field of political science, including classical democratic theory.”

Georgian Straits

Lincoln Mitchell

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Dominant narratives about Georgia’s political crisis fail to capture the country’s complicated and foreign-influenced democratization in the post-Soviet world — and its failure to live up to its ideals. The crisis in Georgia stems from a combination of factors: the ruling Georgian Dream party has taken an increasingly authoritarian, Putin-like turn; the opposition UNM is politically ineffective; and Western missteps, especially by the US, helped enable this repression. These interconnected realities challenge simplistic accounts of the situation.

“Western critics of the GD might wring their hands in frustration, but they (we) must also recognize that even after three decades since the Soviet period, the Georgian democracy movement is still heavily dependent on the West. The more difficult questions with which to reckon are: To what extent is that fact the result of a deliberate strategy on the part of the West, and to what extent has democracy work in Georgia primarily been an assertion of European and American power? My sense is that policymakers in the U.S. and Europe didn’t set out to make Georgia’s democracy activists dependent on the West, but it was always easier for them to ignore how the asymmetry of wealth and power in Georgia favored their views than to take on the hard work of trying to break that dependence.”

What’s The Matter With Abundance?

The last thing society needs is more stuff

Malcolm Harris

The Baffler

Essay

Harris reviews Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. The optimistic book posits that clean energy and a practical sweeping away of over-regulation will clear a path to solve the West’s political crisis with an increase in supplies of necessary goods: housing, clean transportation, lab grown meat. The argument, according to Harris, is a programmatic response to a degrowth-oriented progressive movement, and a conservative movement that detests government intervention. The problem is that the authors don’t grapple with the structural class conflicts that also play a role in blocking the rosy future of abundance.

“It’s one thing to advocate for class compromise, but another to exclude discussion of class conflict altogether. The book’s single mention of Bernie Sanders is in the sentence, ‘In 2016, the rise of Bernie Sanders on the left and the rise of Donald Trump on the right revealed how many Americans had stopped believing that the life they had been promised was achievable.’ Abundance is the prefab, catch-all alternative to these forms of scarcity-thinking on ‘both the socialist left and the populist authoritarian right.’ Large increases in material output, we are assured, can save liberalism from the civilizational choice between socialism and barbarism. I disagree; refusing to be forthright about society’s structural antagonisms opens the door to demagogues who peddle false conflicts that still ring truer than the liberals’ false peace.”

From Nkrumah To Neoliberalism

An Interview With Gyekye Tanoh

Sa’eed Husaini

Africa is a Country

Podcast

Ghana appears to be a stable, neoliberal bastion of democracy in West Africa, but this narrative is belied by spiraling inequality, recurrent debt crises and growing civic unrest. Ghanaian social activist and political economist Gyekye Tanoh contrasts the current situation to the turbulent post-colonial period, which was shaped by clashes between Kwame Nkrumah’s modernizing project and vested interests, both domestic and international. Under Nkrumah, economic growth, though uneven, put the country’s poor on an upward trend, while the current system is structurally dependent on the degradation of workers.

“…The real issue in Ghana is not the resilience of the ruling political parties. It’s the absence of an alternative force that can challenge them in a meaningful way. Now, there is something else happening—a growing disillusionment with electoral democracy itself. Of course, there has always been opposition to governments—that’s why elections exist. But this is different. For the first time, there is a much more widespread critique of the entire political class—a sense that they are all the same and that the system itself is broken. This sentiment has always existed, but today, it is more pronounced, more organized, and more widespread than before.”

Neoliberalism And Its Hegemonic Crisis

Lars Cornelissen

Modern Intellectual History

Journal Article

A review of three books, each offering a different interpretation of neoliberalism in today’s era of surging and exclusionary nationalism: Melinda Cooper’s Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance; Tehila Sasson’s The Solidarity Economy: Nonprofits and the Making of Neoliberalism after Empire; and Jennifer Burns’s Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative. Read together, the three “make for an insightful guide to how its historians are thinking through neoliberalism’s hegemonic crisis from the outside and from the inside.”

“Neoliberalism is neither dead nor dying but mutating, as one excellent volume put it. Yet this does not mean that neoliberalism remains as secure in its hegemony as it was before the global financial recession. If it has survived successive crises, both economic and ideological, it has not done so unscathed. For some time now, neoliberalism has faced a profound hegemonic crisis in which the commonsense appeal it once had, at least in some electoral corners, has notably waned. For at least a decade now, this hegemonic crisis has defined the terrain on which much research on neoliberalism operates. Scholars have been in search of an analytical perspective that is adequate to our present conjuncture. The task is to offer an interpretation of resurgent nationalism that can account for points of tension with previous articulations of neoliberal politics without prematurely declaring neoliberalism dead.”

The Future as a Democratic Resource

Jonathan White

Perspectives on Politics

Journal Article

A flourishing democracy requires strong and motivating beliefs about the future. Future-oriented visions have historically empowered social movements by providing a critical lens on the present, fostering collective political identity, and sustaining commitment through adversity. These visions can also play a role in strengthening the legitimacy of democratic institutions, which rely on imagined futures to bridge dissatisfaction and maintain representation—without them, democracy risks losing its vitality and public trust.

“The political significance of the future tends to be approached in contemporary democratic theory as a matter of what the living may bestow on their descendants. The focus is on cross-generational relations and, more generally, on the futures one can plausibly expect. As this article has argued, at least as important as how things ultimately unfold is how ideas of the future shape politics in the moving present. Hopes, fears, dreams and expectations matter, whether they are fulfilled or not. As politically consequential as how people evaluate the present is how they sense the direction of travel and their degree of control over the future. For both empirical and normative reasons, the study of politics and democracy needs to pay more attention to the ways in which the future is imagined and engaged.”

Jürgen Habermas Calls for Realizing the Ideals of Modernity, not Rejecting Them

Matt McManus

The Bias

Essay

Habermas’ three volume Also a History of Philosophy offers a sprawling and meditative defense of the ideals of modernity. In these books, Habermas traces the evolution of rational thought from mythic and religious understandings of the world toward philosophical reason, highlighting Christianity’s emphasis on human finitude as a turning point that redirected attention inward and laid the groundwork for Enlightenment individualism. He ultimately sees socialism, liberalism, and democracy as rational heirs to this intellectual tradition—secular projects aimed at achieving justice in this world through reason, rather than through transcendence or divine authority.

“At the level of metaphysics and post-metaphysics Habermas’ story is very convincing. It undercuts the bifurcations upon which critics of modernity often lie. The mirror image of the reactionary’s one-sided condemnation of modernity as a great leap down from the past is Stephen Pinker’s one-sided proclamation of modernity as a great leap up. By showing in exhaustive (and sometimes exhausting) detail how modernity was birthed out of antiquity and so carries its genetic stamp, Habermas quietly but radically subverts the reactionary who wants to describe it as an aberrational cataclysm. Moreover by describing modernity as not only developing out of antiquity but improving on it, Habermas shows why modernity should be accepted by critics. If it is the case that modern thought is more rational, more just – a kind of ethical growth as Charles Taylor would put it in Cosmic Connections – and simply more true, then it must be accepted and defended by any who remain sincerely committed to Plato, Aristotle and Augustine’s love of truth, beauty, and wisdom.“