Peronism Now

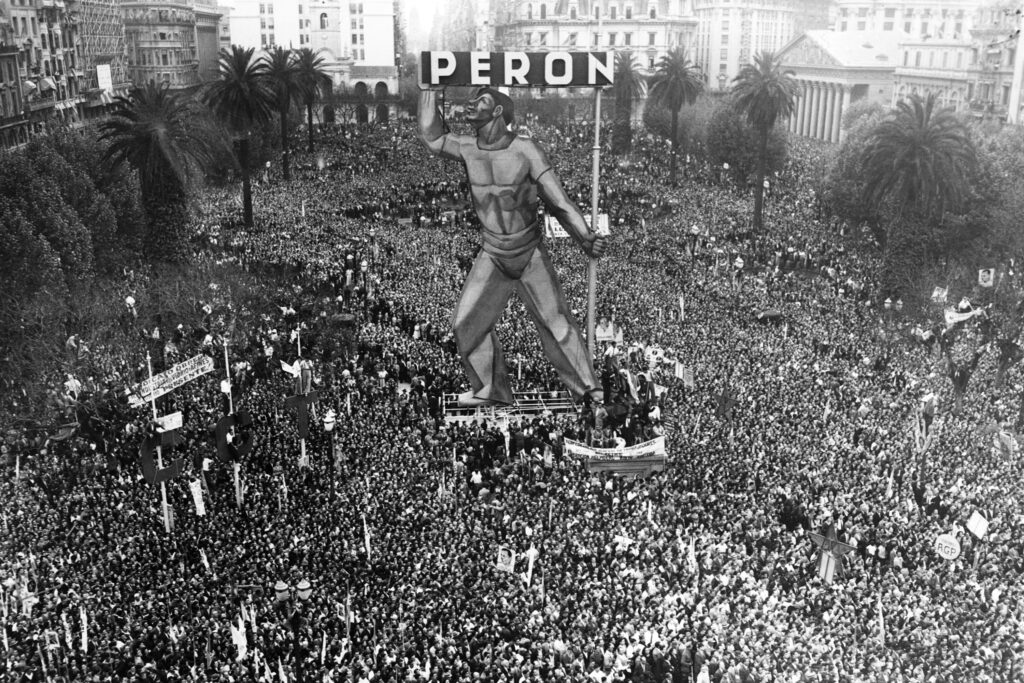

The 14 blocks that separate the national congress building from the executive palace, the Pink House, in Buenos Aires are the epicenter of Argentine politics, formal and informal. Near one end is Plaza de Mayo. On Oct. 17, 1945, masses of workers congregated there to demand the release of their champion, General Juan Perón, a member of the ruling military government who had been detained because he had been amassing too much political clout. The march had an immediate effect: Perón was released by the evening and addressed the crowd from a balcony of the Pink House. With that, protests became a defining feature of Argentina’s political life and turned protesters into the ultimate arbiters of power.

Peronism is a pragmatic and populist labor-oriented movement rooted in redistributive justice, focused on social rights particularly for the lower classes, and for 80 years it won most of the country’s elections. But its representation of the masses was challenged by the surprise victory of Javier Milei, a self-described “anarcho-libertarian,” in 2023, who was elected with the support of angry lower-class voters.

Since its inception, Peronism has been the party of organized labor in Argentina, eclipsing Communists and Socialists, who historically led leftist politics in neighboring Chile and Uruguay. Its governance has not been exemplary, though. As president, Perón persecuted his opponents and silenced his critics, and Peronist governments after him have often relied on clientelist and corrupt practices—as have the country’s other politically viable forces. Some of their economic positions have proven unsustainable, contributing to a perennial cycle of financial crises. But overall they have lived up to their promise to champion the rights of marginalized groups: Over the years, they have enacted female suffrage, paid vacations and other labor rights, free university education, gay marriage, abortion legalization, protections for domestic workers and a child allowance for poor families.

Argentina is a country of frequent and spectacular crises, and during those the people express their adherence or anger, their joy or sorrow publicly, in marches, protests, rallies, banging pots and honking car horns. The streets are palimpsests of our political struggles. Which is why in 2025, as Milei hacks away at hard-won rights with a budget-slashing chainsaw, I look to those 14 blocks in central Buenos Aires to understand how we Argentines will define ourselves in this struggle. For I am a Peronist and, if the party is to survive this crisis, too, its agenda will have to come, once again, from these streets.

The Divide

Buenos Aires has long fancied itself the Paris of South America, but the masses that marched into the country’s history that October day in 1945, demanding that their leader be set free, came from its gritty industrial belt. They showed up in shirtsleeves, the working-class attire that earned them the nickname of “descamisados,” or “the shirtless.” As the people amassed in front of the Pink House under the searing sun, several tried to cool off by wading in the square’s elegant fountains. This irreverence set the tone for Peronism broadly: Beyond its left- or right-wing positions—it has adopted either at different times—the movement celebrates the plebeian, or the “low” in socio-economic-cultural terms, and has consistently challenged social hierarchies, both symbolically and through concrete policies.

These features also help explain its detractors’ deep-seated anti-populism, the other defining force of Argentine politics for 80 years. Peronism is best understood in relation to its opponents. Peronists have always come to power through the ballot box, while efforts to oust them have veered toward authoritarianism (if in the name of defending democracy). Perón won the 1946 presidential elections, not long after that march, and remained in office for nearly a decade, until September 1955, when he was ousted in a military coup dubbed the “Liberating Revolution.” (In an earlier attempt to topple him, which failed, the Air Force bombed Plaza de Mayo, killing 300 civilians.)

The Argentine novelist and intellectual Ernesto Sábato wrote about receiving the news of the coup and what he realized then about the depth of Argentina’s political divide:

“… While we doctors, farm-owners and writers were noisily rejoicing in the living room over the fall of the tyrant, in the corner of the kitchen I saw how the two Indian women who worked there had their eyes drenched with tears. And although in all those years I had meditated upon the tragic duality that divided the Argentine people, at that moment it appeared to me in its most moving form. … Many millions of dispossessed people and workers were shedding tears at that instant, for them a hard and sober moment. Great multitudes of their humble compatriots were symbolized by those two Indian girls who wept in a kitchen in Salta.” (El otro rostro del peronismo, 1956; The Other Face of Peronism)

I read this quote for the first time when I was a teenager and grappling with how to square my history classes’ negative characterizations of Perón, focused on his strongman leadership style, with my leftist father’s affinity to the movement. My father was wont to solve such questions by handing me a book—in this case Joseph Page’s clear-eyed biography of Perón—and with moral reasoning. For him it was obvious which side stood for the greater good. His interpretation undergirds my enduring Peronist allegiance.

Anti-Peronism is as defining a feature of the country’s history as Peronism itself. Since 1945, each side has cast the other as dangerous, and that dynamic has made them co-dependent while undermining democracy. Overthrowing Perón in 1955 wasn’t enough for the reactionary forces that toppled him: They prohibited his party from participating in electoral politics for nearly 20 years after that and banned Perón’s very name from being spoken. Peronist activists were executed. Graffiti celebrated cancer, the disease that in 1952 had killed his wife, Evita.

There is a curious obsession within Argentina’s intellectual class about how a country so blessed with such fertile lands has failed to develop like Canada or Australia. The question is a canard, but the classic right-wing explanation is that Argentina has underperformed because of Peronism’s focus on economic inclusion, which has translated into protectionist industrial policies, stringent labor rights, and costly social services. Detractors claim that they oppose Peronism not on ideological grounds but for pragmatic reasons: A developing country cannot afford the luxuries the party promises, and the lower classes should wait for wealth to trickle down rather than follow its populist siren call.

To posit that a majoritarian political movement is fundamentally misguided is to imply that Argentina’s masses might be unfit for democracy. Yet that is exactly the stance that anti-populists have tacitly adopted throughout Latin America: that populism, the movement that enfranchised much of the region’s masses, has brought democracy to populations unprepared for it, according to the historian Ernesto Semán in “Breve historia del antipopulismo” (“A Brief History of Antipopulism,” 2021). It is unclear to me, however, why it is Peronism that is so often described as the root of Argentina’s ills rather than the bitter hatred and violence of its opponents.

For two decades after the 1955 coup, elected governments alternated with military regimes: Peronism was illegal and any hint of its political resurgence was enough to precipitate another coup, as in 1962 and 1966. But politics without Argentina’s most popular political movement proved unstable and the military government eventually allowed Perón himself to return. He won the 1973 elections by a landslide. By then, however, even he couldn’t overcome deep tensions between his party’s left- and right-wing supporters.

After Perón’s death in 1974, his wife Isabel, also the vice president at the time, took office. She was ousted in a coup in 1976, in the midst of increasing violence by right-wing paramilitaries and revolutionary movements. The dictatorship that followed, Argentina’s last, was its bloodiest: 30,000 people deemed to be dissenters disappeared into a network of clandestine torture centers. In this context of absolute repression, the Plaza de Mayo again played a central role: It was there that the mothers of the disappeared would march again and again, asking for their children’s return, always walking in a circle to defy a prohibition on public gatherings.

God is a Peronist

Some of us tend to see the arc of history bending along with our lives. I was born in 1983, the year that Argentina transitioned from dictatorship to democracy, and my political growth can be measured along the streets bordering the Plaza de Mayo, like a child’s height is tracked with notches up a wall.

Peronism did not win the 1983 elections that ended the dictatorship; it was Raúl Alfonsín’s Radical Party that did, on a promise that democracy would bring prosperity. Alfonsín’s term was cut short by hyperinflation, labor unrest, and the threat of a military uprising. In 1989, he was succeeded by Carlos Menem, another kind of Peronist who implemented Washington Consensus neoliberal reforms—and who after two terms of that had to hand the presidential baton to Fernando de la Rúa and his non-Peronist center-right coalition. De la Rúa then foundered hopelessly in the face of a deep recession and the currency’s collapse, all of which culminated in the dramatic social, political and economic crisis of 2001. On Dec. 20, he had to leave the Pink House in a helicopter to avoid the angry mob in Plaza de Mayo.

The summer before, having just graduated from high school, I had taken to sitting in the square, waiting for the social explosion that seemed like the only answer to such a profound systemic meltdown. The anger was palpable. Demonstrations were multiplying, organized by unions, students, and unemployed workers. In a few months, they swelled into massive, exasperated protests. I went to one of those with my father and sister. We held hands as we fled the tear gas the police sprayed at the pot-banging protesters who were clamoring, “Que se vayan todos!” (“Out with all of them!”).

The experience was a baptism of fire for a generation who had grown up in the apolitical ‘90s. The country’s democracy also came of age in 2001. The multifaceted crisis sparked not a military coup but a profound return to the belief in the relevance of the political. A (Peronist) caretaker government ran the country for a time and then a (Peronist) political unknown, Néstor Kirchner, won the 2003 election. He and his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, would redefine both Peronism and national politics for two decades. Still, like periods past, this one was defined by a hyperpolarized opposition, this time from the conservative right wing led by Mauricio Macri.

The Kirchnerist Peronism of my early adulthood—part of the “pink tide” of leftist governments that swept the region—further expanded social rights and enacted new redistributive policies: more funds for public education, more public universities, laptops for poor children, pensions for informal workers and housewives, rights for domestic workers, public housing. The Kirchners also adopted a progressive narrative of Argentina’s recent history, revalorizing the struggle against the dictatorship that had defined their generation and rejecting the failed neoliberal experiment of the ‘90s. When Néstor Kirchner revoked the pardons granted to military personnel and civilians who had tortured or killed people or made them disappear, he triggered a period of landmark trials that strengthened a new human rights paradigm. Contra Fukuyama, we held a firm belief in history: We knew history hadn’t ended because we were making it.

I returned to those streets countless times in the years after the upheaval of 2001: to oppose femicides, leniency toward human rights violators and budget cuts for public universities; to support gay marriage and redistributive agricultural taxes. In 2018, I joined the angry throngs of women who demanded the right to abortion and failed to obtain it; in 2020, I joined the cheerful throngs sparkling in green glitter who celebrated the legalization of abortion, finally. In my teens, human rights marches had been sparsely attended. Now these were an annual intergenerational gathering.

The country I believe in, the one I want for my children, is to be found in the masses that gather in protest. My father is dead, but I still look for him on these streets and see our shared ideals there. These causes we march for are not exclusive to Peronists; they are shared by other Argentine progressives. But Peronist governments historically have achieved the most advances on these issues: Peronism, like its founder, is pragmatic above all, and to me its concrete achievements so far trump the criticisms.

The Party in its Labyrinth

Between 1983 and 2023, Peronism alternated power with an ever-changing array of ill-fated opposition forces. None of them was ever re-elected, and in two cases, their presidents failed to even complete their terms. Conventional wisdom long held that only the Peronists could govern Argentina’s fractious landscape.

But now it’s 2025 and Peronism is in shambles: rudderless, leaderless, and ignominiously blasted out of the electoral waters by the radical outsider Milei. Not only did he win the presidency in 2023, but so far he has defied smug predictions that he would soon lose power. Milei remains popular with half of the country, despite the high social costs of the austerity policies his administration has deployed to tame inflation. Milei’s success depends on economic recovery. International markets celebrate his single-minded focus on budget cuts, which have been so ambitious that even the IMF has warned Milei that social spending might need to increase to combat poverty. His party is poised to make gains in this year’s midterm elections.

The wheels of the Peronist party machine, stunned by its recent defeat and in need of renewal, are now spinning. Its ideology seems out of touch with contemporary social and economic realities: It has no fresh face to unite its many bickering factions. Has Peronism’s longstanding dominance over Argentina’s political life finally ended?

Its historical claim that it is a party of inclusion—for workers, women, minorities—has foundered against an extended period of economic decline, high inflation, and rising poverty The conservative Macri government (2015–19) failed on similar issues, but at least it never pretended to have a socially progressive agenda. The latest Peronist government was that of Alberto Fernández, seconded by Cristina Kirchner (2019–23). Their coalition was rife with infighting and governed defensively; it became the party of the establishment, rather than that of social reform. Perhaps most damning has been the Peronists’ inability to grapple with their own failures, including the fact that a new socioeconomic class of the excluded arose under their watch.

Milei has been able to tap the frustration of Argentina’s increasingly marginalized populations, with a populist discourse that flips Peronism on its head: He has recast the historical party of the disenfranchised as the leader of a thieving political establishment. Milei has also deployed many of Peronism’s own political strategies against it, in particular to capture the votes of a new class of workers: those in the growing informal sector. That precariat had been excluded from the labor protections and social-subsidy net that are the backbone of Peronism. Milei has struck at the heart of Peronism’s raison d’être, pointing out that the movement has failed to respond to the changing needs of social justice.

Milei follows the outsider-politician playbook. He has capitalized on a wave of anti-establishment sentiment against both leftist Peronist and conservative anti-Peronist governments. He originally painted the two sides of the Kirchner-Macri divide with the same brush, labeling both as “the caste” and promising to free citizens from the yoke of all corrupt politicians. Given Argentina’s long-term economic malaise, his campaign did convince voters desperate for change, any change. Milei seemed to offer a possible exit from the schism.

The political scientist David Runciman argues that today representative democracies are not facing the totalitarian threats of yore but rather a midlife crisis of dissatisfaction. Argentina’s political woes resemble the challenges that democracy faces in Brazil and the United States. (And the Peronists have been losing touch with their traditional electorate for similar reasons the U.S. Democratic Party has with its own.) Peronism has lost the powers of conviction it had during the years of my early adulthood, and for my peers and I, who grew up in democracy and are now in our 40s, the notion that we should stick with this side because the other is worse feels threadbare. The popular anti-establishment anger captured by Milei needs a concrete response, not just a harangue. Are we done with Peronism?

No: Rumors of its death have been greatly exaggerated. This moment is hardly the movement’s first crisis. Critics argue that Peronism lasts because it’s an ideologically empty carapace with a Zelig-like ability change with the times. Perón himself cultivated the ambiguity between his leftist and right-wing followers—which resulted in bloody confrontation in the ‘70s. Detractors often point to this to delegitimize Peronism as an authentic political movement, but it surpassed the inclinations of Perón himself long ago.

If anything, according to the anthropologist Alejandro Grimson, Peronism’s success has been built on its ability to impose political hegemony (in a Gramscian sense) in response to changing times. Grimson writes in ¿Qué es el peronismo? (What is Peronism?) that to define Peronism narrowly is to leave aside what he calls its “constitutive heterogeneity.” Peronism, which had relied on a strong working class, managed to survive the death of the industrial economy in the neoliberal ’90s under Menem and then thanks to the Kirchers’ pivot to a constituency that also included the urban poor, social organizations, and progressive middle-class sectors.

The Peronists’ strength historically has been their ability to channel the popular demands of the time; Milei’s success is built on their failure to perform this trick in recent years. But when he has been forced to seek political allies to shore up his legislative agenda, Milei has often adopted the classic Peronists vs. anti-Peronists trope. Milei hasn’t overcome the schism: He is just the latest iteration in a long line of virulent anti-Peronists.

Milei has benefited from this divide, and from anger at the political establishment, and hasn’t yet suffered a backlash against his administration’s austerity policies. But his strategy could boomerang. Milei campaigned on promises to make “the caste” pay for economic adjustments; in reality, his fiscal surplus has been financed by significant cuts to pensioners and educators, to health care and other social programs.

This is an opportunity for new Peronist leaders to pull the rabbit out of the hat and reinvent the movement—now justly reviled as a political elite—as a champion of social justice for a new generation, a changed economic landscape, and an informal gig-based labor market. As Leopoldo Marechal, a mid-century surrealist Peronist poet, wrote, “every labyrinth is exited from above.” Peronism’s electoral strength depends less on its legacy to date than on its ability to remain relevant. So far, though, a stagnating agenda and infighting have prevented the party from coalescing around a new viable leader: Cristina Kirchner is still its strongest voice, and her image is tattered.

“We’re all Peronists” (apocryphal)

It might be time for a divorce, for a new party, for a new movement. But the emotional pull of Peronism, while hard to define, shouldn’t be underestimated. The historian Juan Carlos Torres says it “has the strength of a religious faith or loyalty to a soccer team.”

The demonstrations of Plaza de Mayo aren’t just protests. They are also markers of celebration, after electoral victories, or of communal sadness. When Néstor Kirchner died on Oct. 27, 2010, throngs of silent mourners spontaneously gathered in the square throughout the day—and then they held a raucous wake outside the Pink House that lasted three days. When Diego Maradona died in 2020, not even pandemic restrictions could stop the Plaza de Mayo hordes. And remember the delirious celebrations after Argentina’s World Cup victory in 2022?

Argentine politicians listen to the street. Following the death of two activists at the hands of security forces in 2002, the Kirchner government adopted a principle of “non-repression” when it came to protests. Although the Macri administration partially renounced it, the security forces still largely tolerated demonstrations. The kind of violence Chilean protesters faced in 2019 would be beyond the pale here.

But when Milei came to office, he promised to crack down and initially sought to limit public gatherings of more than three people. His government has implemented an elaborate machinery of repression—which criminalizes traffic disturbances and gives the police broad powers to disperse demonstrations. It stomps on human rights in the name of the freedom to drive through the city.

There has been remarkably little social unrest given the level of economic pain, but a few impactful gatherings are challenging Milei’s efforts to redefine the country. Massive protests have been held against labor deregulation and the defunding of public university education. Again on March 24, like every year since 1985, people marched to commemorate the victims of Argentina’s last dictatorship. The latest protest, in Buenos Aires on Feb.1, was an antifascist, antiracist march—attended by an estimated one million people—that had been called in defense of minority rights after Milei railed against “the mental virus of woke ideology.”

Argentina’s politics are in crisis and its progressives are floundering, but protests continue to delineate our outer limits, to establish what we are not. Peronism could once again be the party that best translates the sentiments of these demonstrations into concrete governance. To resurge, though, the movement will have to redefine its understanding of the struggle for social justice. And that means writing our future, much as we have written our past, on those 14 blocks of Buenos Aires’ streets.

Jordana Timerman is a journalist based in Buenos Aires, she edits the Latin America Daily Briefing and is part of The Ideas Letter team. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The New York Times, Le Monde Diplomatique, Cenital, Revista Anfibia, Americas Quarterly, and Boom, among others.