We lead Issue 33 with a tale about Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, the noted (and notorious) gene-editing technology better known to us mortals as CRISPR. Science writer and researcher Melanie Challenger employs here the concept of pollution, a term of art from an earlier Industrial Revolution, to make sense of the externalities inherent to this new transformational moment.

The LSE Law Professor Siva Thambisetty, immersed in the arcane world of treaties and conventions, follows, raising the thorny question: What do we mean by “equity” when we debate global governance? As she makes abundantly clear— it’s not as clear or fair as it should be.

Our last commissioned piece comes from LuHan Gabel, who considers some of the assumptions of the essay penned by Nicholas Bequelin for our last Ideas Letter, on the diminished power of human rights institutions. Gabel brings a new angle to some of Bequelin’s observations, and her suggestive critique widens the aperture on his argumentation. (We anticipate a Bequelin response in a future issue.)

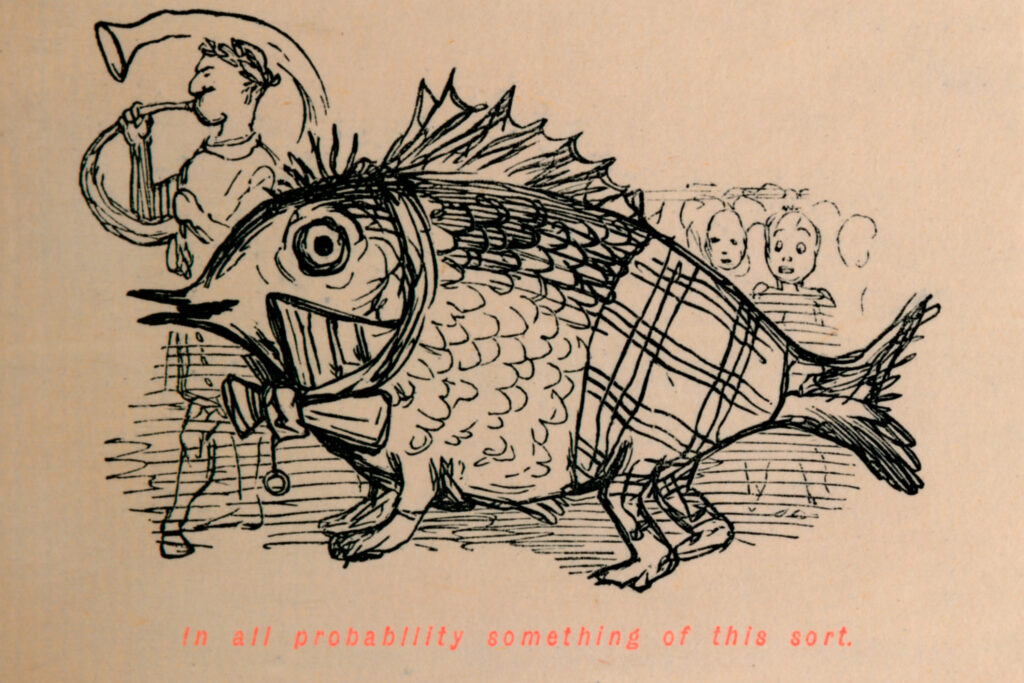

Our curated pieces begin with a hotly-debated cover story in Harper’s by Dean Kissick. Entitled “The Painted Protest,” it is an obvious play on Tom Wolfe’s scandalous book from the 1970s on modern art, The Painted Word. The piece has been receiving, unsurprisingly, much discussion.

We follow with an incisive essay from Sagar, a Bihar-based writer, published in The Baffler: It is a cogent essay on the intense role that caste still plays, despite all, and the way it continues to insinuate itself into so many aspects of life in India, generally for the worse.

We are glad to feature the writer Mana Afsari who, with humility and intellectual conviction, makes her way (pointing to interesting themes galore) through a set of ideologically-laden conferences, beginning with NatCon. Yes, Virginia, there is a way to be ecumenical about ideas without rancor or recrimination.

Last, from the LRB, Susan Pedersen unpacks—takes apart, really—a new title that is fixed on the political economy of NGOs and liberalism after empire. Pedersen shines a light on what role nonprofits have actually had in the confection of (putatively) neoliberal charitable efforts.

Our musical selection for Issue 33 is dedicated to the memory of Michael Burawoy, the exceptional public sociologist just retired from the University of California, Berkeley, who was killed by a hit-and-run SUV driver this week. Burawoy brought ethnographic research to life, and his students, who revered him, will likewise keep his own memory alive. We offer a piece Burawoy I think would have treasured: the folk icon Phil Ochs performing his early anthem “Power and Glory.”

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Gene Editing is Pollution

Melanie Challenger

The Ideas Letter

Essay

CRISPR, the revolutionary gene-editing technology, is ushering in a new era of industrialization—one that directly manipulates biological life—and this has profound ethical and environmental risks. Challenger argues that much as with the combustion engine, the rapid adoption of CRISPR could lead to unforeseen consequences, and she urges us to rethink genetic engineering through the lens of pollution and establish safeguards before its full impact becomes irreversible.

“What is curious about the Fourth Industrial Revolution is that while several branches of science are arming us with the evidence that justifies an expansion of the moral circle to encompass a larger range of organisms, other branches are cranking up the objectification and exploitation of life-forms. As a result, there’s an obvious gap. Without addressing this, most concepts of pollution will remain anthropocentric. This may prove a critical misstep.”

The Equity Trap

Siva Thambisetty

The Ideas Letter

Essay

International treaties often claim to promote “equity” in benefit-sharing, but their vague language frequently enables wealthier nations to outmaneuver developing states, particularly in biodiversity governance. The 2023 Ocean Treaty broke this pattern by leveraging expertise, coordination, and a strategic approach from the Global South: It created a tangible system for sharing benefits from genetic resources from the high seas. This success highlights the urgent need for enforceable expert-backed mechanisms in global negotiations—rather than hollow commitments to fairness—so as to ensure true equity in international agreements.

“Today, many major deals are being negotiated, formalized and legalized even as a full understanding of their scientific and economic implications is only still emerging. Expert advice is not simply a question of money, time and competence; it is also about trust, insider knowledge and a form of kinship within groups. Diplomacy at the UN can be opaque and intensely hierarchical, and getting access to diplomats and their advisers is often the most challenging aspect of marshalling and using expertise. Many momentous decisions are made on the fly by busy negotiators who are already thinking about the next week’s talks on another deal.”

Is it all about power?

A response to “Human Rights on the Edge”

LuHan Gabel

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Gabel critically examines the alleged decline of human rights as a global movement in her response to Nicholas Bequelin’s recent Ideas Letter essay, “Human Rights on the Edge.” To establish genuine moral authority, the human rights system must challenge Western dominance and acknowledge the agency of nations shaped by a postwar order they did not create, she argues. This will require understanding those nations’ motivations for engaging in global governance despite structural inequalities. Gabel draws on her experience in the disability rights movement in China to argue that the human rights enterprise should not be an external “authoritative arbiter.”

“When the audience is a human rights organization or the international criminal justice system, underwritten by liberal states, victims unavoidably speak the language that they think this powerful machine would understand. Historically, it had always been more difficult for women to articulate the injustice they suffer because when they appeal to the powerful for redress, they face a recognition barrier. Often, the framework they needed to tell their stories truthfully did not exist. This applies to all who are not blessed with political or material power. They are also the intellectual future of the human rights movement as new frameworks come alive through their telling.”

The Painted Protest

How politics destroyed contemporary art

Dean Kissick

Harper’s

Essay

Kissick argues that contemporary art’s focus on identity politics has led to formal conservatism and a nostalgic yearning for the past. He contends that this shift stifles creativity and reduces art to a vehicle for social justice messaging, thereby diminishing its aesthetic and emotional impact. Kissick calls for a return to art that embraces experimentation and innovation, free from the constraints of political agendas.

“The project of centering the previously excluded has been completed; it no longer needs to be museums’ main priority and has by now been hollowed out into a trope. These voices have lost their own unique qualities. In a world with Foreigners Everywhere, differences have flattened and all forms of oppression have blended into one universal grief. We are bombarded with identities until they become meaningless. When everyone’s tossed together into the big salad of marginalization, otherness is made banal and abstract.”

Further Viewing

Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse and Dissonance in African Art Traditions

Wole Soyinka, Hutchins Center

In this 2017 lecture, Soyinka argues that Yoruba religious and cultural traditions, by persisting despite historical suppression, colonial plundering, and religious demonization, have demonstrated unique resilience both in Africa and the diaspora. He criticizes the destruction and misrepresentation of indigenous heritage while emphasizing the adaptability and enduring influence of Yoruba spirituality, particularly its ecumenical approach to faith and cultural identity.

“The Yoruba welcomed both Christianity and Islam—millions converted, but few fully, fully repudiated the penetrating gamut of their precedent acculturation. A case very simply of, ‘You can take the Yoruba out of Yorubaland, but you cannot take the Yoruba out of him.’ … Clearly, this is unique to the Yoruba; it is, however, robustly observable and even demonstrable in many instances wherever the Orisha have trodden. The cultural retentions from centuries are ever-discernible in powerful manifestations—from cuisine to the visual, the performance arts, the rhythms, even the melodies, the chanting, and literature, especially drama.”

Twice Born

India’s emerging majority is a caste majority with regressive ideas

Sagar

The Baffler

Essay

India’s political majority is shaped not by religion or economic concerns, but by caste-based allegiances that reinforce hierarchical and regressive social structures. While the BJP capitalizes on Brahmin supremacy and lower-caste aspirations to sustain its dominance, the persistence of caste-based discrimination ensures that even shifts in control over political power fail to dismantle the entrenched inequalities that fundamentally define India’s democracy.

“The very formation of caste majorities preserves inequality, religious hatred, segregation, and class supremacy—ideas which can’t be called liberal for a democracy. A numerical minority here can emerge as a majority, not as a result of demographic change or reform, but by way of birth. … In a caste majority, regressive ideas and violence are attributed to accidents of birth and the basic tenets of democracy—liberty, equality, and fraternity—are negated. A numerical low-born minority, in a caste democracy, will have to struggle for even basic civil rights. Their emergence as a majority, the least prevailing of liberal ideas, will forever remain a dream. Conversely, a high-born minority will always be a ruler of a caste democracy.”

Last Boys at the Beginning of History

Thymos comes to the capital

Mana Afsari

The Point

Essay

Afsari examines the rise of young, intellectually engaged men who see Donald Trump not just as a political disruptor but also as a model of greatness, ambition, and defiance in a cultural landscape they feel has marginalized them. Through firsthand reporting from conservative intellectual circles and political conferences, she argues that while liberalism has failed to inspire this generation with a compelling moral or philosophical vision, the U.S. nationalist conservative movement has successfully provided it with a sense of purpose, community, and historical significance.

“Somehow, the National Conservatism conference—home to a movement emphasizing national loyalty, marriage, civic responsibility, religion—had tapped into energies that felt, to many, fresher, freer and wilder than the once-natural home of soulful young men and women—the left or liberalism. The NatCons addressed questions of the heart, recognizing that the young need ideals and aspirations—and most of all, a vocation.”

Slim for Britain

Susan Pedersen

The London Review of Books

Essay

Pedersen reviews Tehila Sasson’s book The Solidarity Economy: Non-Profits and the Making of Neoliberalism After Empire, which argues that British international aid organizations, rather than merely succumbing to neoliberalism, actively embraced and propagated its tenets—entrepreneurialism, consumerism, anti-statism—shaping post-imperial economic relations in the process. For Pederson, the book offers compelling archival research and illuminates the intersections of voluntarism and market ideology, but she questions its broad claims that non-profits “made” neoliberalism.

“I closed her book feeling appreciation but also frustration. Some marvellous research, especially in the Oxfam archives, underpins it. Sasson explains some things that have puzzled me for years, not least why 11,000 charity shops survive in the UK. Her attention to the elective affinity between the voluntary sector’s long reliance on individual service and the entrepreneurial culture of neoliberalism, and to the way this fed efforts to foster indigenous production, is illuminating. But affinity is not causation, and it isn’t clear just how much significance one can accord to the work of these charities in ‘making’ neoliberalism, or even in making some of the specific reforms discussed.”