The Return of the Future and the Last Man

An Interview with Ivan Krastev

Carlos Bravo Regidor: The year 2024 is coming to an end and it might be fitting to kick off this conversation by asking you about its significance—not necessarily in terms of what is to follow, but rather in terms of what has happened and what it means retrospectively. How would you assess 2024 in light of where we were coming from and where it leaves us?

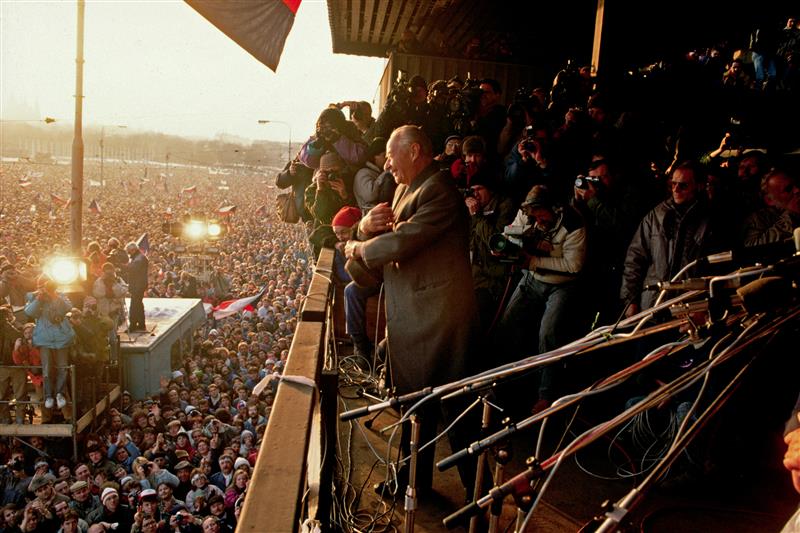

Ivan Krastev: 2024 is certainly going to be remembered as a turning point. When the year started, everybody was pointing at its unusual combination of wars and elections. And there was this sense of change, of something ending and something else starting, and that was felt everywhere. But the strongest sign of the fact that we’re living in a moment of radical change is not what we’re discussing about the future; it’s what we’re discussing about the past. If you look at 2024 and you go back to the debates about what happened in, for example,1989, you’ll see how different that conversation is today. Because, in a certain way, it’s not simply about this cliché that the post–Cold War world was ending: It’s more about how we’ve realized there was always something about it, something more, that we weren’t ready to see. And now we are.

Today we see 1989 as something more than the fall of the Berlin Wall; it was about the massacre at Tiananmen Square, too. So, it meant not only the end of communism in Europe, but also the resilience of communism in China, which has turned out to be quite important, perhaps even more important, historically. And 1989 was significant for radical Islam: It was that year that for the first time an Islamist country defeated a superpower. In fact, a 2019 survey conducted by the Levada Center, an independent pollster, asked Russians what was for them the most important thing that happened in 1989, and most answered not elections in Poland, not Tiananmen, not the Berlin Wall, but the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. That wasn’t about the end of communism; it was about Moscow losing its superpower mystique.

And 1989 very much marked a nationalistic moment. In Yugoslavia, it was then that Milosevic delivered his famous speech in Kosovo, essentially telling the Serbs that he was there to defend them.

The major story about 1989 we got used to was that we were sure about the direction in which the world was going, on which side history was supposed to be. This was based on a certain understanding of democracy, of liberalism, of the international constellation of hegemonic power and so forth. But looking at this from 2024, we now know that story isn’t relevant anymore. The only thing we know today is how fast things are changing, including our past. We can’t be sure about direction anymore; we can only be sure about speed. The late Eric Hobsbawm used to talk about the “short 20th century,” referring to the period from 1914 to 1989; well, in 2024 we are witnessing the end of the long 20th century.

CBR: Ten years ago, you published Democracy Disrupted: The Politics of Global Protest (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), a book about the spread of massive protests all over the world. You interpreted those protests as genuine articulations of discontent and distrust but argued they were lacking an actual political project. In your formulation, they ended up being about “participation without representation”; they were an unequivocal rejection of the status quo yet offered no vision of an alternative future. Actually, the whole 2010s were a decade of massive social mobilization, but, alas, they didn’t produce a more democratic nor a more egalitarian world. Why not? What, then, was the legacy of that decade of contestation without imagination?

IK: When we talk of 2024 retrospectively, of going back and revisiting the importance of certain things, we surely have to discuss the 2010s as a decade of strong social movements. Some people might not remember this, but it all started with the Arab Spring, which then became a global phenomenon; people took to the streets almost everywhere. What happened was a very strange yet strong articulation of a certain post–2008 financial crisis sensibility, after trust in capitalism was shattered. Nevertheless, these movements didn’t make a claim for power: People were protesting but they rejected having any political leaders. In a way, the protests were about the experience of protesting itself, about the performance or the pedagogy of changing society by just going out there. Nobody really put a claim on power; nobody said “I want to govern” or “I will govern differently” or anything like that. The demonstrators’ demands were much more modest than the size of their crowds.

Another important aspect of these protests was that they were, in many countries, kind of a middle-class thing; quite a lot of educated people took part in them. There was also a very strong generational dimension to them. Both their middle-class nature and the fact that they were articulated in the language of youth culture explain, at least partially, why these movements never claimed power. But being born of distrust, they were also defeated by distrust, because if you aren’t ready to trust and delegate, you cannot govern.

Finally, one of the major stories about this kind of mass mobilization, at least in my view, is that authoritarian leaders then used them to try to consolidate their power. People went on the streets to say, “We are the society!” and these leaders responded, “I am the majority!” This was very much what Erdogan did, for instance, when he went up against the Gezi Park protesters in 2013. It’s also a clue that Putin’s decision to invade Crimea in 2014 should be understood as a response to the middle-class protests in Moscow of 2011-12.

CBR: Was that, in a certain way, Putin’s own idiosyncratic interpretation of an Occupy movement?

IK: Totally! Yet it appears that the problem with the protest movements was that they were occupying but they were not annexing.

CBR: When I finished reading Democracy Disrupted, I was left with the impression that certain kinds of protests in certain circumstances might end up working against democracy. But in Is It Tomorrow Yet? Paradoxes of the Pandemic (Allen Lane, 2020), your book about Covid-19, you make a very forceful argument about how the pandemic threatened democratic politics on a very essential level because “democracy cannot function if people have to stay indoors”—meaning that there is no democracy when there can’t be street protests. How have your ideas about the value of street action and its relationship to democracy evolved since you published those books?

IK: I’ve always believed that protests are extremely consequential for people to actually feel that they live in a democracy. You see, elections matter not simply for what they represent, but also for what they don’t represent. They represent the interests, the values and so on of the voters, but they don’t represent intensity. You might have very strong feelings about something, I might not, but each of us has a vote. So, the best way to show how much one cares about certain things is not through the ballot but on the streets. Particularly if you’re trying to convey the significance of something, want to put on the public agenda certain issues that are not the preoccupation of the majority of the population, protests are critically important. Intensity is also a signal to policymakers that they cannot rely on elections alone, that voting is not enough for democratic governance, and that some people are ready to take a risk and come out because of the strength of their beliefs—willing to break certain rules, occupy a space, etc.

Protests can be energizing. They can push governments to do things that otherwise they wouldn’t do. But they can also become an excuse that governments can take advantage of, an excuse to deploy authoritarian measures that would otherwise seem illegitimate to those people who are not on the streets. So, in a sense, protests make clear the choices that governments face. Are those governments going to use the protests as a way to rejuvenate democracy, to strengthen the people’s feeling that their voice matters? Or will governments use them as a pretext to silence the opposition and destroy a democratic regime? Both options are there; which one is chosen very much depends on the context and the leaders in power.

CBR: In Is It Tomorrow Yet? You wrote that the change Covid-19 was bringing about wasn’t a new version, either authoritarian or democratic, of the “end of history,” but a less ideological and more unstable future. Among the many paradoxes you discussed in that book, there are two in particular that I would like to examine with the benefit of hindsight.

One is the paradox that we were eager to return to normality but would discover it was impossible to. Yet, four years after, it seems that the page has been turned and that a certain normalization has taken quite a strong hold, fueled not so much by a nostalgia of the world as we knew it before but by a neurotic effort to forget about the pandemic as much as we can. It’s like a paradox upon a paradox: No matter how disruptive that experience was, today we try to live as if it just hadn’t happened.

IK: Yes, I agree. But, let me tell you something: That book was written very early on during the pandemic. I’ve always believed that situations like that, pandemics or wars, are like love—you either write a book at the start or when it’s over; in the middle, things are just too muddy. I’m grateful for your question because it allows me to revisit the impact of the pandemic, the strange ways in which it was transformative, and the intuition that we’re going to have more and more experiences like that one in the future.

To begin with—and this is something I write in the book—we should recall that probably more people died from the 1918 influenza (some estimates say 50 million people but others as many as 100 million) than during World War I (16 million–17 million) or World War II (60 million). Between just 1918 and 1920, what was long called the “Spanish flu” may have killed just as many people, or even more, than both wars taken together. Yet nobody remembers it and everybody remembers the wars. And I mean not only regular people but also historians: As Laura Spinney describes in her superb history of the period (Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, PublicAffairs, 2017), a search in one of the largest library catalogues (WorldCat) found about 80,000 books on World War I in more than 40 languages but hardly 400 about the “Spanish Flu” and in just five languages. Why? Well, maybe because it’s hard to turn a pandemic into a good story: It seems like such a random thing; it lacks a plot and a moral. During a pandemic, death becomes sort of meaningless, even undignified: There is nothing heroic in it; many people die without a proper funeral. It’s strange, moreover, because you don’t even know exactly who to blame for those deaths. So, in a certain way, it isn’t so surprising that we just tend to not remember. We cannot know how people will remember or forget Covid in the end, but my guess is that at least in Ukraine or Gaza the pandemic has already vanished from the memory of the people destroyed by war.

My major argument now, looking back, about the Covid-19 pandemic is different. Because even if we forget it, the pandemic had major impacts in three different political ways. I would even argue that its legacy was critically important for Trump’s second victory in the United States.

The first impact was that when the Covid-19 pandemic started, some key differences between democracies and authoritarian regimes disappeared. Almost everybody was doing the same thing. Lockdowns, masks, this and that—suddenly governments acted like governments, no matter the kind of regime. And I believe this blurring of the distinction between democracy and authoritarianism is something that has stayed. I’ve always liked making comparisons and contrasts, but now they’re becoming increasingly complicated to make. Do you recall that US Supreme Court justice, Potter Stewart, who famously said that pornography was hard to define but, “I know it when I see it”? Well, I believe that with authoritarianism these days it’s just the opposite: It’s easy to define, but are we sure we recognize it when we see it?

The second impact of Covid was that, on the one hand, people suddenly discovered that they need a government and, on the other hand, governments showed they can care for the people. Many countries turned the pandemic into another Great Depression or a warlike project. The United States under Joe Biden is a great example. It had a classic F.D.R. moment: There was a major transformation in all sorts of policies, stimulus, regulations, huge public investments; people were willing to tolerate high levels of spending and so on—all of this was very much justified by fear of the virus and the scale of the crisis. But three or four years later, people’s thinking is now going back; they think these measures were excessive, partly because of the rise in inflation that resulted. Besides, some major groups—particularly those working in the informal sector—were quite angry even back then about the prolonged lockdowns and felt they weren’t really taken care of. I believe some of the Latinos in the US who used to support the Democrats but now vote for Trump might be doing so because of that. Perhaps in the past they saw this kind of more interventionist state as an ally, but in 2024 they might be seeing it more as an obstacle.

And this extends beyond the United States. I was talking to a colleague in Argentina and he was claiming that the lockdown experience was one of the reasons young people supported Milei in the last election. Because they felt they had had to deal with many restrictions but hadn’t received enough help. In general, when the pandemic started, everybody focused on older people, senior citizens, because the risk for them was much higher, right? Well, now that the pandemic is over many young people probably see themselves as its main victims: because of the closing of schools, the lost job opportunities, and also because of the social isolation—all that time they ended up spending in front of their screens made them much lonelier. These sorts of backlashes against government intervention are quite important to understanding the legacy of the Covid experience.

The pandemic’s third main impact was a profound shift in political identities, ranging from the left to the right. There was a softening or mixing up of standard ideological distinctions, centered around a strong articulation of mistrust toward the state, toward anything coming from the government. A culture of suspicion arose that has cut across the normal cleavages and has opened a space allowing people to change where they stand politically. What happened with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is a good example of this. Naomi Klein touches on something critically important in that regard in her latest book, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2023): Suddenly the border between fringe and mainstream thinking collapsed. There is a surprising readiness, in the current intellectual environment, to buy into any type of conspiracy theory. Mistrust has become the default option; only the naïve now trust what they are told by the government. Which makes the advent of the so-called post-truth, fake news and all of that much more important. It’s not only about supply; there is demand, too. For some people the easiest way to deal with a conspiracy theory is to buy into another conspiracy theory.

I’m always going to remember a story a friend of mine, a Bulgarian living in the US, told me about this. During the pandemic, she was in a hospital waiting room and a woman started saying to her, “You shouldn’t get a vaccine; those who are vaccinated will be chipped.” She was referring to the infamous conspiracy theory targeting Bill Gates about vaccines being used to implant Microsoft tracking chips into people. My friend, who happens to be married to a doctor, was tired and didn’t have the time nor the disposition to have any kind of normal conversation with this person, and so she told her: “Yes, there is a conspiracy, but you’re getting it wrong. Everybody who doesn’t get vaccinated is going to die. There are too many people in the world, a decision was taken to reduce the population, so only those who get the vaccine will survive.” The woman looked at her and replied, “I knew there was something behind this! OK, you’re right, I’ll get vaccinated.” Many people are now willing to believe almost anything they are told if it isn’t coming from the traditional communication channels. And they can easily shift from one conspiracy theory to another, and move from the left to the right. It doesn’t really matter: What remains constant is the lack of trust in mainstream institutions.

CBR: The second big pandemic paradox that I want to touch on is about protectionism gaining momentum globally. You already saw that coming in Is it Tomorrow Yet? —and you were wary. Because in this day and age, as you wrote, “nationalism is economically unsustainable,” but also, if the world is really going protectionist, you warned, effective protectionism is possible only on a larger, regional or even continental, level.

In Mexico, for instance, there are a lot of expectations regarding nearshoring as the most viable option to ride out the new wave of protectionism within the North American space, that is, in partnership with the United States and Canada. But some American and Canadian leaders have already signaled reluctance about that, scolding Mexico for potentially becoming a sort of Trojan horse for Chinese goods and influence in North America. They are not substantiating their allegations; still, this calls Mexico’s geopolitical belonging into question, which is quite an unprecedented move. And in Europe, protectionism doesn’t mean strengthening the borders between European countries; it means strengthening the outward borders of the European Union. That might make some sense economically, perhaps, but the problem is that even as the politics of neo-protectionism become more popular, they are still formulated in a rather national or nationalistic framework. So what would a political path for de-globalization through regional protectionism look like?

IK: This is a very interesting question, because the answer is very different from region to region. Strengthening the external borders of the European Union has indeed become a kind of a new consensus, but the situation is very complicated because Europe needs immigrants given the aging of its population. Its borders cannot be totally closed. Perhaps the story isn’t about opening or closing those borders but about changing their nature. Still, a decision will need to be made about who is going to be let in and who isn’t. Other places, like China, are so big that, in a certain way, they are more like a continent than a country. Same with India. Mexico is in a sort of intermediate position: It’s a big country but very close to the United States, so its opening or closing depends on the Americans. Besides, Mexico has become a transit country.

Strangely enough, at the same time that there is all this new talk about protectionism, geographies are changing. I was recently following Brazil’s idea of developing new infrastructure to make it much easier and cheaper for Chinese goods to come to Brazil and also Latin America. Because protectionism doesn’t mean that you’re simply going to create some regional economy; you’re also probably going to change the infrastructure of your regional economy to work with others. So, here’s a paradox. On one level, of course, countries want to protect themselves, improve their industries, secure their production, etc. But on another level, the very meaning of sovereignty in today’s world is about having options. Before, the major story was about which side you were on; during the Cold War, the choice was between the Americans or the Soviets. Nowadays, in order to signal how important you are, you need to show that you can be part of any number of possible alliances, and maybe several at once. Turkey is a great example of this. It’s a NATO member, it wants to join the EU, but Erdogan also went to Kazan to take part in the latest BRICS summit. The more clubs you belong to, the more you can convince your own population that you have agency in the world.

Moreover, one of the things that has happened in recent years—and this is quite interesting—is that the question of who is a given country’s largest trading partner, or where most of that country’s foreign investment comes from, doesn’t say much about its geopolitical loyalties. That main partner is probably going to be China or the US, here and there, but that doesn’t mean the country is aligned or allied with them. The thing that best predicts the geopolitical loyalties of a state is which other states it’s sharing data with—that, in many ways, is the most important fact. And this points to a much bigger story about technological walls. Tell me what kind of technology you use and I will tell you where you stand geopolitically. Is it American or Chinese? Are you allowing Huawei to be part of your national telecom system or not? There’s the traditional story about protectionism—industrial policy, trade, tariffs and so on—which is very easy to see. But that might not be where the core geopolitical competition lies, because today’s walls are less visible than those during the Cold War.

And there are many uncertainties. For example, Trump says he wants to impose 60 percent tariffs on Chinese goods. Many people are asking themselves if he’s really going to do it, or if he’s just bluffing, or if he’s trying to improve his position at the negotiation table. The same has happened many times with Putin’s threats, too. I believe the best way to understand this sort of leaders is to take them at their word. Putin told us that he was going to invade Ukraine, we didn’t believe him, and he did. I think Trump is basically telling us what he wants to do. So, if he does do it, what happens next? The Chinese will probably look for other markets in strategic places, like Mexico, perhaps even by trying to use the framework of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement in their favor. Suddenly, then, Trump’s tariffs could cause a more aggressive global China, which is going to be more political than before. If the Chinese are expelled from parts of the US market and forced to look elsewhere to sell their products, they will ensure they have enough influence to prevent non-Western countries from adopting anti-China tariffs. Because if the Chinese are going to increase their investments in places like Mexico, believe me, they aren’t going to be indifferent about who governs there. Chinese mercantilism will turn much more openly political. In my view, China’s growing investments in Mexico, and its growing trade with Latin America, are the most serious challenges that the United States has faced as a regional power. They can dramatically increase tensions and can affect not only the economy but also the politics of countries like Mexico.

Protectionist politics are now perceived as legitimate policy by different players. Yet they are harder to put in practice for smaller countries than for bigger ones. But even those who believe they can afford them don’t know what the unintended long-term consequences will be. And I mean that not only in economic terms, regarding production and prices and so on, but also in terms of political power, of geopolitical loyalties.

CBR: Something I find fascinating reading your work is how you develop a truly global perspective and yet always remain anchored in your Eastern European experience. This is particularly salient in books like After Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017) or The Light That Failed (Pegasus Books, 2019), coauthored with Stephen Holmes, where that perspective is placed front and center, very explicitly, in how you interpret phenomena like the politics of the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe or the debacle of liberal democracies all over the world. How would you characterize the intellectual intention of that perspective?

IK: I appreciate that question because for me, regardless of where anyone has been or what they’ve read, their view of the world is very much shaped by concrete time and concrete space. And this is particularly true when you go through moments of major transformation. I’m an East European of a very particular generation: I was 25 years old in 1989, and one of the things that is always going to stay with me from that moment is the sense of how fast things can change.

Eastern Europe is one of the most Eurocentric places in the world, much more so than Western Europe. Eastern European countries never were imperial; they suffer none of that guilt. In fact, East European countries were born out of the disintegration of three continental colonial empires—Ottoman, Habsburg and Russian—and so we basically carry this kind of anti-imperialist, anticolonial legacy; that’s how our nation states were built. At the same time, all the models we have are very much European.

Moreover, in the 1960s and 70s Eastern Europe was perceived as quite important for some newly independent countries. It’s no accident that one of the greatest reporters of the anticolonial revolution of that period was the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski. Because he knew two things that were crucial for the world at that moment. Being a leftist Pole, he knew something about revolutions, but as a Pole who lived under the Soviet Empire, he also knew something about imperialism. It’s kind of instructive that he wrote, on the one hand, all these books about different types of anticolonial revolutions, all these chronicles that start with him taking a plane, then landing somewhere and telling a story. On the other hand, his last book, Imperium (Vintage, 1995) was not about him going somewhere abroad; it was about the Soviet Union coming to his country.

After 1989, Eastern Europe was also crucial in Western discourse. The “end of history” arrived in Eastern Europe in a very peculiar way. In the classical liberal story of the post–Cold War period, what happened in Eastern Europe then was also going to happen in many places at some point. On the eve of 1991, some believed that there were two types of countries in the world: The majority, like Poland, where democracy could grow from the grassroots, and the others, like Iraq, where democracy would have to be sown with the help of the US Air Force. From that point of view, there was a certain universalization of the East European experience—but the West got that wrong, because most of the world was not like Eastern Europe.

Finally, I believe that Eastern Europe was oddly well prepared to understand the promises and failures of European societies that followed, and we were probably better able to grasp certain things that have happened in other places since, including in the United States. When in 2016 some people started saying that they didn’t understand Trump, I realized I had no problem understanding what he represented. After he won, the same people said that they didn’t know what he was going to do, and again, I sort of did. Why? Because I had seen this phenomenon before as an East European. Even though Eastern Europe totally lost its geopolitical centrality for anybody who wasn’t interested in Europe, I have the feeling that our history has a certain type of heuristic value. Besides, I’ve never believed that I can see the world with anything other than Eastern European eyes anyway: My point of view is very much rooted in my experience coming from a small village in a small East European country, from the periphery of the periphery

CBR: In The Light that Failed, co-authored with Stephen Holmes, you discuss how liberal democracy is going awry all over the world. The book argues that the “losers” of the Cold War engaged in a politics of imitation that bred a lot of anger and resentment, fueling what John B. Judis has called “the populist explosion.” That claim makes a lot of sense, but it took a rather unexpected turn later on with the rise of that same kind of politics in Western Europe and the United States, the Cold War’s supposed “winners.” How are we to make sense of this?

IK: Well, what was the “end of history”? It was a moment about which basically Francis Fukuyama, very much following the logic of modernization theory—and not simply Hegelian thinking—argued that the world had reached a sort of final destination, that ideological competition was over. His theory held that the world’s future would not look very different from the West’s present in 1992. By the way, Fukuyama was not exactly fascinated by that future and wrote that the last man was going to be quite bored, essentially just a consumer and very uninspiring.

The “end of history” kind of turned time into space. Germany became the future of Poland. Poles had a choice: They could wait for their country to become like Germany or they could migrate to Germany and start living in the future immediately. This narrative, a form of time travel, created a major movement of people. It also transformed the far-right parties as they turned the ballot into another sort of time-travel machine—this one going backward: By vowing to expel migrants, they were promising a return to the world of yesterday. That was an important part of our argument.

Another major argument Holmes and I made was about the expectation that while Eastern Europe was going to become like the West, the West was going to stay just the way it was. Many countries are paying a very dear political price for that illusion today. Back then this was perceived as very normal, but the moment the rest of the world started changing, guess what happened? The West started changing too. This is a major development, and it’s the reason I believe that we are today at the end of a certain historical period. Real change is happening—not because the purported “losers” of the Cold War have managed to mobilize, but because the “winners” have started to perceive themselves as the ultimate losers. That’s the story of the period we’re currently in. Trump is essentially telling Americans: “The elites told you we won the Cold War, but they lied to you. The real winner was China, and it’s taking our jobs. They’re not telling you the truth. America is not the real hegemon. We have been taken hostage by them, by NATO, by Mexico—basically everybody is abusing us.”

This change is critically important to understanding what’s happening. With the rise of new authoritarian leaders and far-right movements in the West, winning the Cold War turned out to be a big lie. Before, the prevailing narrative in the West was based on a very simplistic premise about imitation, namely that all the others wanted to “be like us.” But the argument of the book is that relations of imitation are much more complicated and contestable than that. Sometimes I try to imitate you not because I want to be like you, but because I want to beat you, replace you. And it’s that kind of story, in which suddenly everything you thought were your strengths you start perceiving as your weaknesses, that really inspired Holmes and I to try to explain what was happening. Here’s a very simple example. Until about ten years ago, Europeans thought Europe was the greatest place in the world and that everybody wanted to immigrate there; now the same people are saying that everybody wants to go there and that that’s the worst thing that has ever happened.

CBR: Speaking of immigration, why did you write in After Europe that “the refugee crisis turned out to be Europe’s 9/11”?

IK: On Sept. 10, 2001, America had a certain view of the world, of itself and its vulnerabilities, of how others perceived it. Then 9/11 happened and all of that changed. Well, I believe something like that also happened in Europe with the refugee crisis of 2015. And it was very important not so much because of the number of people who came to Europe, but because that crisis transformed the idea of borders that had been at the core of the European project.

After 1989, Europe wasn’t simply about tearing down walls, about people crossing borders, about redrawing those borders. Europe was about changing the very nature of borders, about making them easy to cross and almost invisible. And all of that was very much challenged with the refugee crisis.

Different kinds of borders create different types of identities. Ken Jowitt—a brilliant American political scientist, though not very well known—who wrote a truly great book called New World Disorder (University of California Press, 1992), argued that some borders are like barricades that create very firm identities you just cannot change. During the Cold War, for instance, you were either in the East or in the West. In beautiful metaphorical language, Jowitt wrote that a world divided by barricades is like a Catholic marriage: There is no divorce; you basically stay where you are. Other borders are more like frontiers, lines between large and open spaces that are rather easy to cross, and the identity those borders confer is only whatever identity helps you survive. Possibilities seem unlimited; no decision is fateful. It’s more like a one-night stand, an encounter with someone whose name you might not even remember the next day. In my view, that very easiness, much like the borders within the European Union, is prone to creating an identity crisis.

In my books, particularly in my book with Holmes, I often go back to Albert O. Hirschman, an author both Holmes and I hold in very high esteem. In his classic work Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (Harvard University Press, 1970), Hirschman explained that when people are disappointed, they react in one of two ways: They push for change or they leave; fight or flight. In the market, for instance, if you’re dissatisfied with a Pepsi product, you might first complain to the company. But if things don’t change, you’ll simply start drinking Coca Cola, because moving from one brand to another isn’t an existential issue for you. But, as Hirschman recognized, it’s not so easy to leave your family, your political party, or your country, because your loyalties lie with them. Interestingly enough, for Hirschman loyalty was such an obvious force that he didn’t devote much time conceptualizing it. But in the last decades or so, we’ve started living in a world in which leaving your family, your party or your county has become somewhat like shifting from Pepsi to Coca Cola. And that’s a very dramatic change. That, in some ways, is the larger story about the immigration crisis.

In Eastern Europe, as we argued in The Light That Failed, the migration crisis isn’t so much about fearing the people who are coming: Not too many people have wanted to live in Bulgaria, in 2015 or even now. It is, rather, about the trauma of the people who have left many East European countries—according to some estimates, about 20 million Eastern Europeans left, basically for Western Europe, between the early 1990s and the mid 2010s. And this, alongside Covid, has prompted questions like “What is happening to us?” and “Are we going to survive?” If the pandemic forced all of us to face our own individual mortality, migration is forcing small countries to face the mortality of their national community. This is something Holmes and I have been working on lately: the demographic anxieties of a world in which people are moving all the time, there aren’t enough children in some places and identities dramatically change with movement. The population of my own country, Bulgaria, is the fastest-shrinking of any state in the world that isn’t experiencing war or some natural disaster. The combination of low birth rates and massive emigration has resulted in a panic, and Bulgarians are starting to imagine that in a hundred years nobody will speak their language anymore.

That’s why, for me, the 2015 refugee crisis was Europe’s 9/11. Of all the crises that Europe has been facing for the last 15 years or so—the global financial crisis, the climate crisis, Covid, the war in Ukraine and so forth—I believe the immigration crisis has been the most consequential politically: We’re seeing its impact in every election.

Beyond Europe: I believe Trump managed to take advantage of this very successfully. During the US presidential election, the Democrats focused on his racist remarks and attacks on different ethnic groups, but one of his major arguments was about migration, about those “illegals” who should not be allowed in, much less to vote, who should be deported, etc. In the end, his message was about how the most important difference in the US ought to be between citizens and non-citizens.

CBR: Immigration has become a subject that allows citizenship to be weaponized as an acceptable criterion for discrimination?

IK: Yes, absolutely.

CBR: The last chapter of After Europe is called “Perhapsburg: Reflections on the Fragility and Resilience of Europe.” It makes an argument that isn’t exactly optimistic but that is clarifying and that, in a way, turns the conventional diagnosis of European integration upside down: Because Europe is facing so many adversities, people tend to think that it has become both weak and outdated, yet its very survival might be a testament to its strength and necessity. In the 1990s, Europe was thought of as a project in search of a reality. Perhaps 30 years later it should be understood as a reality in search of a project?

IK: You’re totally right. And listen, I have quite often been accused of being pessimistic. But I keep on telling people that I am neither optimistic nor pessimistic. Both optimists and pessimists share something that I don’t, and that is a predisposition to believe we can somehow anticipate what the future is going to look like. I believe that the future is open, uncertain, and that is precisely why I try to be hopeful.

Of course, Europe has proven to be much more resilient than many had thought possible. And I have always believed that its survival is critically important. That’s why in After Europe I quoted Rilke: “Who speaks of victory? To endure is all.” Surviving a crisis creates legitimacy for any political project; all nation-states are nothing less than a collection of survival stories of different kinds. From that point of view, I do believe Europe still has a purpose. You’re totally right in pointing out that Europe is surviving, but Europe’s identity is changing and not as a product of public deliberation. Europe today knows less about itself than it did, for example, two decades ago. The European Union used to be a project, yes; perhaps today it’s very much a survival mechanism for its member states and their societies. Is that a problem? I don’t know. Probably this is how the world works. And probably at some point Europeans are going to conceptualize better what they want to do.

Europe is now very vulnerable because in times of dramatic change, such as in our world today, the most vulnerable are those actors that were the biggest winners of the previous game. And the European Union was indeed the biggest winner of the post–Cold War era. So much so that war on the continent was just unthinkable before the Russians did what they did in Ukraine. European societies were really on a holiday from history. Now the holiday is over, and Europe faces major economic and security threats.

From time to time, when I’m kind of in a bad mood watching what’s happening in the EU, I recall an old film with Peter Sellers, Being There. The protagonist is a gardener who has spent all his life tending a mansion’s garden and watching television; he has no experience of the outside world. When the owner of the mansion dies, the gardener is kicked out. The first time he wonders around in the streets, he suddenly finds himself being attacked by some gangsters. Having spent his entire life watching television, when a thug wields a knife to his face, he takes a remote control out of his pocket and tries to change the channel. Every now and then I feel like Europe’s responses to the crises we’re facing today are just like that, that we’re just taking the remote control out and trying to change the channel.

CBR: In the conclusion of The Light That Failed, after arguing that we are going through the end of an era, you wrote: “the end of the Age of Imitation will spell either tragedy or hope depending on how liberals manage to make sense of their post–Cold War experience. We can endlessly mourn the globally dominant liberal order that we have lost, or we can celebrate our return to a world of perpetually jostling political alternatives, realizing that a chastised liberalism, having recovered from its unrealistic and self-defeating aspirations to global hegemony, remains the political idea most at home in the twenty-first century.” Five years after having published those words, where would you say we are now?

IK: I think a lot of people make the conceptual mistake of confusing the end of liberal hegemony with the end of liberalism. But liberalism is very much part of the fundamental human experience of putting limits on power. Yes, the triumphal liberalism that was going to transform the world is just not there anymore. And Trump’s second victory should push liberals very strongly to revisit what’s happening and why.

But a good thing about the difference between individuals and ideas is this: While we don’t have any proof that individuals can be resurrected, ideas never die. It’s fascinating to see the return of an interest in Marxism or in the end of capitalism or even in a certain type of historically conservative ideas that everybody believed were dead forever. Well, the same will be true for liberalism, although now liberalism will be different, much more contextually centered. Liberalism is not about a world without borders; it’s about a world in which you can cross borders based on individual decisions. But the crossing of borders comes at a cost. How are borders going to be reconceptualized? What will be the limits of power? What can we do collectively? All those questions remain, but the answers are not going to be what they were in the 1990s. The arrogance of liberals is one of the worst things that happened to liberalism as a result of its hegemony. Many liberals behave as if they’ve been betrayed by history, but history is married to nobody.

CBR: I know you’re very interested in the metamorphoses of democracy and, more specifically, in the revival of assertions around the concept of sovereignty today. What do you see as the promises or perils of this sort of neo-sovereigntist turn?

IK: Democracy is also a story of bounded communities. Democracy does not create political communities, but it cannot exist in the total absence of borders. Who is in and who is out is critically important, because democracy is about loyalty, about solidarity, about what we decide to do together as a political community and, thus, about how we understand sovereignty. The concept has had very different understandings throughout history. There was a moment where the sovereign was God, then it was the State—whether in the form of the King or the People—and during the last liberal decades I think the sovereign was the Individual. In a certain way, almost everything was reduced to individual choices.

But suddenly all those choices started to look equally important. And one of the problems of this age we’re talking about is the extent to which lack of commitment has become an everyday experience. For example, I’ve always been stunned and mesmerized by the fact that you can go to one of those big fashion shops, buy a dress and then return it 24 hours later, not because there’s something wrong with the dress, but because you changed your mind. We’re living in a world in which basically everything can be re-decided very easily. And I do believe that part of the story about this new sovereigntist moment is that it shouldn’t be so easy to re-decide. It should be clear that there is a difference between choosing and picking.

At the level of international politics, it used to be that in order to keep or improve their status, countries and their leaders behaved a bit like in the old regime: Their best bet was to try to marry into a prosperous family. So, for instance, when a small country like Bulgaria joined NATO or some other organization, that made it look important. But now it’s like the world has gone on Tinder, and some countries, like Turkey, as we discussed before, want to show that they have lots of options, that they can do many things. It’s an exhausting exercise.

But for people, it’s very important to know that they can decide on something. Precisely because everything is perceived as a choice, we’re making choices all the time. This, in a sense, has created the central cultural contradiction of contemporary life that democracy is now contending with: On one level, everything is our choice; on another level, we feel incredibly powerless. So how to reconnect the idea of individual or collective choice with the notion of actual power is, I find, critically important.

CBR: What other developments or innovations have caught your eye lately? What social trends or political shifts are you paying attention to? What are the ideas or intellectual currents that you are most interested in nowadays, at the end of 2024?

IK: Well, I’m currently working on another book about something that absolutely fascinates me, and that’s the politics of demographic imagination.

We’re living in very interesting different times. Between 1965 and 2015, as Martin Wolf recently wrote in the Financial Times, the fertility rate of the world halved. Many people today are living in societies where fertility is below the reproduction level. This is our current demographic reality. And then there are the demographic projections—the future is no longer a project; it has become a projection—and those could be wrong, but many are quite astonishing. The population of South Korea, for instance, could be halved over the next 50 years. This means a very different age structure, with very few babies being born and the older generation becoming the biggest cohort. How is democracy going to function when the young just don’t have the numbers to ever become a majority? Or take Russia, as I argue in a recent piece with Holmes in Foreign Policy, which today has a population of around 145 million but which, according to some projections, by the year 2100 could count as few as 74 million Russians in Russia proper. This is quite a problem for a country obsessed with portraying itself as a strong world power.

When you focus on democracy and demography, and particularly on the way political decisions are taken based on demographic anxieties and fear, you find a number of authoritarian states where people are blaming low fertility rates on the spread of Western cultural values. This creates a whole new set of tensions and conflicts. I’ve been arguing, for instance, that it’s hard to understand Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine without considering how concerned he is with the demographic decline of Russia; his only successful policy to increase Russia’s population has been the annexation of Crimea. If you look close enough, you can see this kind of biopolitics playing out all over the globe. You can see it also in the case of the recent American elections, in the fear that suddenly the government is going to “elect” its people, so to speak, by granting citizenship to people who vote for its camp or taking it away from those who vote for the other party.

I’m not interested anymore in discussions about the end of history and the last man. I’m much more interested in the return of the future and the last man. The last man defined by the demographic imagination is different from the last man defined by the environmental imagination or by the technological imagination. A lot of people are worried about the climate crisis, about the possibility that we could be the last humans on earth; others are worried about a sort of technological takeover, about machines and software replacing all sorts of human labor. Funnily enough, the problem with the demographic imagination is that it posits no such thing as the last human; it’s all about the last Bulgarian or the last Hungarian and so on. Even as some Silicon Valley types are talking about the immortality of the individual, we’re facing the mortality of nations, of family, of having children—of the traditional ways in which people used to fight their mortality. I see this as a dramatic change with incredibly important political consequences. This is the thing that at the moment is at the center of my attention.

CBR: About the second Trump presidency and its potential reverberations across the globe: It feels that in the coming months we’ll be forced to live through a “fasten your seat belts” moment, bracing for impact. What kind of surprises, for better or for worse, might occur in the months and years to come as a result of Trump’s reelection?

IK: Great question. Oddly enough, for me the most telling sign lies not so much in the election results as in Trump’s early announcements about nominations to his cabinet. This moment reminds me so much of Bulgaria in the 1990s, when a journalist could very easily become the defense minister because of the political divide, because what really mattered was not competence but loyalty. In many ways, the leadership was putting people in posts not because they would know what they were doing but precisely because they wouldn’t—and that meant they were capable of breaking the system, of wreaking radical change. But the biggest problem with radical change is that it can have unintended consequences. We basically know what kind of things Trump is going to do, but we don’t know how the world is going to react.

I believe, for example, that Trump is absolutely saying what he thinks when he claims that he is going to stop the war in Ukraine in 24 hours. The problem is that it’s not only up to him. Where is the Russian president going to stand on this? Or if Trump imposes high tariffs on products from China or other countries, what are they going to do? The more radical the action, the more unintended the consequences it can produce. Some of them could be positive, some negative. But there is one thing that cannot happen, and that is a return to how things used to be.

In my view, the recent US election marks the end of an era. Before, when someone was trying to oppose Trump or political leaders like him, their pitch was, “Vote for our camp because we represent normality and we’re fighting against something weird”—a term American Democrats have actually used. Well, there’s no normality anymore. If there’s going to be an alternative to Trump and the like, it should be an alternative that’s well spelled out, not just a vague hope about going back to the past. Trump isn’t only killing the world of yesterday; he is also burying it.

Carlos Bravo Regidor is a writer and political analyst based in Mexico City. He is a regular contributor at Letras Libres, Expansión Política and El Heraldo de México.