This edition of The Ideas Letter, our seventeenth, spotlights someone you may have not yet run across. Almut Rochowanski has been in the salt-mines of feminist activism and politics, principally in the Northern Caucasus, for decades. In recent years from her redoubt in the northeastern United States, Almut has begun to think critically and reflectively about what made sense, and what was effectively nonsense, during those years “on the ground.” What she calls her bildungsroman is indeed an effort to understand how she came to know what she now knows. It makes for riveting and necessary reading.

We are thrilled that the esteemed Japanese philosopher and champion of degrowth, Kohei Saito, agreed to respond to Oliver Eagleton’s critique from our last issue. Here Saito defends the emancipatory possibilities around what he has called degrowth Communism, and why Eagleton’s critique of the concept’s romanticism is misplaced.

Our video feature in this issue is a tough-minded conversation on the thorny topic of decolonization. Some of our finest minds on the theme—Paul Gilroy, Lydia Polgreen, Hisham Aidi, Ayisha Osori and Brian Kagoro debate its utility and coherence for grasping contemporary political realities, especially in the Global South.

Following nicely on the decolonization discussion, we begin our curated content with South African Sean Jacobs’ revisiting of Pan African festivals during a time when power, identity and négritude took pride of place. We would like to dedicate Sean’s essay to the memory of our partner and friend, the Nigerian journalist Rotimi Sankore, who died at only 55 earlier this year. Rotimi was working on a documentary about Fela’s writing at his death, a film that Sean and so many others would have loved.

Kalundi Serumaga, another partner of ours, is up next, with a bracing piece on Uganda’s deep and enduring commitment to neoliberalism. No surprise, Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, one of the world’s longest reigning dictators, comes in for considerable responsibility.

From neoliberalism to genocide, we are honored to feature the foremost authority on human rights and justice, Aryeh Neier, and his celebrated New York Review of Books piece calling the catastrophe in Gaza as a genocide. Aryeh, a co-founder of Human Rights Watch, has always set the standard for meticulous interpretations of human rights’ reality, and this piece is no exception. We have added two essays for contrast and supplementary reading from Omer Bartov and Amos Goldberg.

Alexander (Sasha) Etkind is up next with a provocative essay from the brand-spanking new CEU Review of Books on the alleged causality between petro-states and conflict—both in terms of war and climate. It makes for an exciting read.

We conclude with a piece that deconstructs the current hegemonic concept of diversity. How does DEI square with so-called viewpoint differences? Can they be integrated? Can they form a more holistic understanding of the idea of diversity?

Our musical selection this issue comes from Mexico via Cuba. The great bandleader/arranger Pérez Prado was dubbed the “Mambo King” and this 1949 dance hit “Mambo no. 5” makes clear why. Prado lived in Mexico for much of his life from where this was recorded. Enjoy the infectious Mambo grooves!

—Leonard Benardo, senior vice president at the Open Society Foundations

Rethinking Foreign Aid (From the Inside)

Almut Rochowanski

The Ideas Letter

Essay

This week, a majority of lawmakers from Georgia Dream, the country’s ruling party, overrode a presidential veto of a controversial law intended to limit the influence of ‘foreign agents’ in civil society. Rochowanski problematizes the story of Western foreign-aid and philanthropy’s support for the civil society sectors in the former Soviet Union during the post-Cold War period, in the context of her own personal bildungsroman as a feminist activist over the past decades.

“A radical critique of our sector starts with truly accepting people and communities in places like Georgia as our equals. This means seeing—really seeing and acknowledging—their capacity for managing their own affairs in their own way. It goes much further than the twee “de-centering” we practice, in which a Western donor might forego sitting in the center of the stage, even though they’ve paid for the stage, the speakers on the stage, the travel and hotel rooms of all the guests—guests that were hand-picked by the donor. The best I could come up with are things we have been doing all along, if not in Georgia or anywhere in the former Soviet Union, but here at home, where democracy and accountability are real to us. We can’t rid money of its Midas touch, but we can change the dose, like that of any poison.”

Further Reading

Georgian nightmare

Thomas de Waal, Englesberg Ideas

Domestic resistance to the Foreign Agents Law ruling party lawmakers pushed past a presidential veto this week has been broad: “If Georgian Dream thought they would get opposition only from the ‘usual suspects’—urban Tbilisi professionals and those whom it could label as supporters of small opposition parties or promoters of ‘LGBT propaganda’—they miscalculated The core of the resistance has come from self-mobilised young people who grew up in democratic Georgia and smell authoritarian rule in the air, though the public as a whole does not seem to like it either.

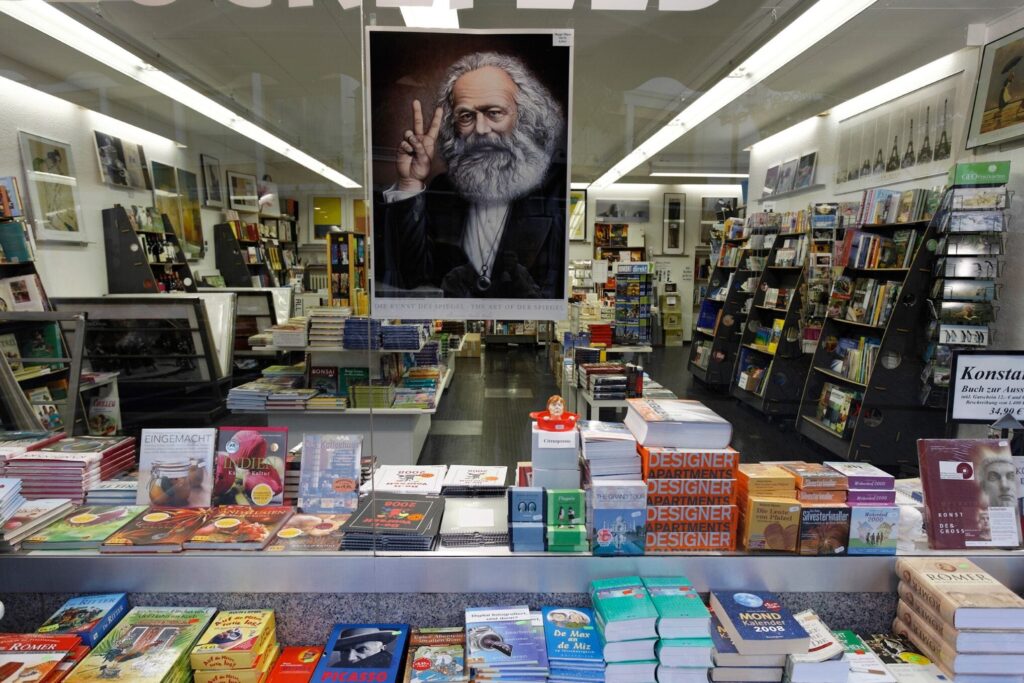

How Marx Can Save the Planet

The Case for Degrowth Communism

Kohei Saito

The Ideas Letter

Essay

Oliver Eagleton’s criticisms of both degrowth and ecomodernism in the last issue of the Ideas Letter are legitimate, but he fails to truly try to overcome the tension between the two concepts, and instead argues that one must resist the temptation to synthesize, according to Saito. “A postcapitalist utopia is not about offering concrete proposals for a new society; it is about refusing to ‘foreclose the future.’” Despite traditional Marxist avoidance of mapping out concrete alternatives to capitalism, “a response is needed to the young generations’ yearning for unlocking the real value of post-capitalism,” replies Saito.

“Marx’s idea of ‘degrowth communism’ offers the synthesis of ecomodernism and degrowth by eliminating the ambivalence of ecosocialism. … Adding ‘communism’ to ‘degrowth’ demystifies the idea that degrowth is about going back to a pristine state of nature. One of Marx’s fundamental insights was to say that the development of productive forces under capitalism creates material conditions for realizing free and sustainable development for all humans. Local, bottom-up eco-villages and community gardens cannot protect us from a planetary ecological catastrophe. A much more systemic transformation is essential—and socialist politics can help scale up degrowth to challenge the capitalist system by universalizing means of production, democratic planning and public services. Adding ‘degrowth’ to ‘communism’ strips Marxism of its narrow focus on productivism by recognizing insurmountable natural limits. Productive forces cannot be sustained beyond a certain point, no matter the mode of production. Any society, capitalist or communist, that pursues infinite growth eventually rarefies resources. In contrast, degrowth aims for a post-scarcity economy by encouraging sharing and mutual help.”

Decolonization

The Ideas Workshop

The Ideas Letter

Video

Many concepts draw more heat than light when politically and intellectually contested, and decolonization is one of these fraught ideas. Decoloniality features a range of assumptions which may shift depending upon the context in which it is being applied. Although an agreed-upon meaning may be out of reach, a shared sense of what different people might understand by the term is not. This illuminating conversation between Lydia Polgreen, Paul Gilroy, Hisham Aidi, and Brian Kagoro, and hosted by Open Society Foundations’ Ideas Workshop, sheds light on the complexity of these debates around decolonization.

Lydia Polgreen argues that “the past shapes us and creates us in ways that we can’t possibly escape and therefore we actually have to engage it in the most thoroughgoing and explicit terms. There’s a difference between being engaged with the past and trying to understand the past and thinking about the past as setting us on a determined path. I think if there’s one thing that I just am kind of constitutionally opposed to it’s this kind of essentialism and this kind of determinism, because I think I fundamentally believe, and this is another place where I where I appeal to Fanon,I really believe in human agency and invention and the capacity for creative future building.”

Chop-Chop Spirit

Sean Jacobs

London Review of Books

Article

A series of Pan African state-sponsored festivals of art, music, drama, poetry, literature, film and dance held in Senegal in 1966, Algiers in 1969 and Nigeria in 1977 show evolving visions of négritude, pan-African culture’s relation to decolonization, and the relationship between African nations and international Black movements. The keystone event was Festac ’77, an enormous gathering in Lagos, Nigeria, of at least 15,000 delegates from more than 50 countries to celebrate and invigorate the “pan-African nation.” Contemporary critics, like Wole Soyinka, pushed back against the corrupting effect of public financing: “Festival spirit there was none, only the chop-chop spirit—‘eat your own and I eat mine’—that began from the very top leadership of the organisation, percolated through the entire bureaucratic set-up and, to my intense distress, even infected the artists.”

Nonetheless, Jacobs speaks of “The headiness of that time for Nigeria and the black world. The material also makes clear the festival’s ideological diversity. According to Andrew Apter in his 2021 article ‘Festac ’77: A Black World’s Fair’, Festac’s idea and vision of black culture and civilisation was ‘less concerned with policing boundaries and more about expanding them’. As a result, ‘communists from Cuba, capitalists from Côte d’Ivoire, and Marxists from Mozambique could promote competing political economies of culture within a welcoming celebration of common heritage.’”

Lest We Forget

against 40 years of Ugandan neoliberalism

Kalundi Serumaga

Review of African Political Economy

Essay

The National Resistance Movement (NRM) has ruled Uganda for 38 years—and with it so have the divisive principles of neoliberalism. A recent conference at Makerere University, in Kampala, provided an opportunity to look back at the results, and future, of neoliberalism’s tenure. Serumaga observes that young academics bemoan the poverty and instability wrought by neoliberalism, while finding that they fail to promote a viable alternative. So where does Uganda—and neoliberalism—go from here?

“This brings us to Uganda today; we have the first and probably the most committed neoliberal regime in Africa, something that made President Museveni the absolute darling of the West. Regarding the aforementioned violence, history shows ours to have been the product of not one but two coups. … Just as imperialism at home sought to find a way to erode the Social Democratic policies, it also always wanted to do so to the gains created ultimately by the real and original anti-colonial 1920-1949 movement … which gave us trades unions, the right to elect lower reps, agricultural co-operative unions, affordable credit, currency autonomy, and trade protection. As said, this is because all these things formed barriers to greater exploitation.”

Is Israel Committing Genocide?

Aryeh Neier

New York Review of Books

Essay

Life-long human rights activist, and Open Society Foundations president emeritus Aryeh Neier does not use the term genocide lightly. Though he believes Israel has the right to retaliate against Hamas for the murderous attacks it carried out on Oct. 7 last year, “I am now persuaded that Israel is engaged in genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. What has changed my mind is its sustained policy of obstructing the movement of humanitarian assistance into the territory.”

Though human rights organizations are blocked from Gaza “limiting the ability of these organizations to gather information and make detailed reports on the conflict hardly insulates Israel from criticism for its abuses. That is because international observers judge the conflict in Gaza on the basis of principles and assumptions that the human rights movement has helped to establish.”

Further Reading

What I Believe as a Historian of Genocide

Omer Bartov, New York Times

“In order to prove that genocide is taking place, we need to show both that there is the intent to destroy and that destructive action is taking place against a particular group. Genocide as a legal concept differs from ethnic cleansing in that the latter, which has not been recognized as its own crime under international law, aims to remove a population from a territory, often violently, whereas genocide aims at destroying that population wherever it is. In reality, any of these situations—and especially ethnic cleansing—may escalate into genocide, as happened in the Holocaust, which began with an intention to remove the Jews from German-controlled territories and transformed into the intention of their physical extermination.”

More Further Reading

Yes, it is genocide

Amos Goldberg, Mekomit

English translation at The Palestine Project

“Although each case of genocide has a different character, in the scope and features of the murder, the common denominator of most of them is that they were carried through out of an authentic sense of self-defence. Legally, an event cannot be both self-defence and genocide. These two legal categories are mutually exclusive. But historically, self-defence is not incompatible with genocide, but is usually one of its main causes, if not the main one.”

Oil, Climate and War

The curse of the petrostate

Alexander Etkind

CEU Review of Books

Essay

Wealth that is generated by oil production—commonly referred to as the “oil curse”—often leads to authoritarianism, corruption, and prolonged conflicts in petrostates. These countries, including Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, engage in aggressive military actions more often and for longer than non-petrostates: the oil funds the wars. They also significantly contribute to climate change while downplaying its effects, part of the complex interplay between oil-driven economies, political instability, and the global climate crisis.

“If we see it as a polycrisis, we assume that contemporaneity of the war with decarbonization is just a coincidence. If we see the crisis as hierarchically organized, with the climate crisis as its main reason, we acknowledge the causal relations between decarbonization plans and the actions of the petrostates.”

How Diversity Became the Master Concept of Our Age

Nicolas Langlitz

Chronicle of Higher Education

Essay

Most diversity practices aim for social justice by making schools and workplaces reflect the general population. However, in research and higher education, diversity is also valued because it’s believed that diverse groups produce better knowledge. The two different types of diversity—one focused on social justice and the other on viewpoints—are often posited as conflicting, though they are, arguably, synergetic.

Langlitz outlines an “epistemological and political paradox at the heart of diversity”: “An ideal diversity would need to be inclusive of the many forms that nondiversity and even anti-diversity can take. In reality, however, diversity is always selective and advances the viewpoints and interests of some groups at the expense of the viewpoints and interests of others. A “view from everywhere,” as Lorraine Daston called it in a talk on objectivity in the humanities, is no more realizable than a view from nowhere; both are at best regulative ideals.”